The Last Supper (13 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

Jim renews his offer of mince and tatties. Imperiously, I refuse. I say that I do not want mince and tatties. I do not want the fodder of the cold North. Even the idea of them sticks in

my throat. I want to remain loyal to the ardent suppositions of my own imagination, to my southern ideal, whether or not it exists. Jim is very offended. I have to apologise several times before he is appeased.

*

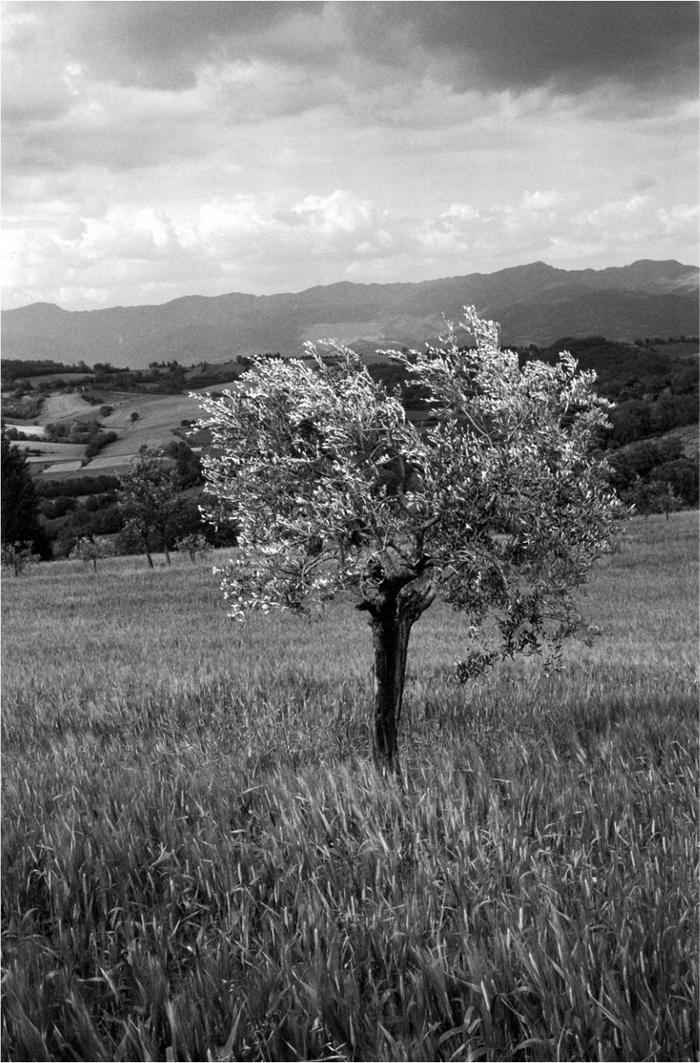

In the field near our house there is a grove of olive trees. Their biblical forms are so ancient, their fruit so bitter: they are like the ancestors of the cultivated earth, so dry and bitter-tasting in their wisdom. Their subtle leaves make an antique filigree pattern against the duck-egg-blue sky.

The corn is starting to show in its pregnant husks and the fields sway with wheat. There are apricots and peaches and

cherries at the fruit stalls. On the road to Arezzo people are selling truffles and walnuts and mushrooms from the front doors of their farmhouses. We buy a bag of cherries and eat them, meditatively spitting out the stones. We buy big rough discs of bread. We buy a lettuce, and a fennel bulb like a swollen green knuckle. We buy a jar of truffle paste. The Italians make

bruschetta

with truffle paste. It is dark grey and closely textured. For a while we eat it, until I realise it is beginning to arouse feelings of disgust in my suspicious palate. The truffle paste makes me think of something horrible. One day, while eating it, it occurs to me that it is like eating puréed mouse.

We eat things that are red, white and green, like the Italian flag. Yellow, that area of the food spectrum so favoured by the English, has disappeared. So has brown, the colour of sausages and gravy and a cup of tea. We eat hard little

cantucci

biscuits and drink espresso. We eat sheep's milk cheese and tomatoes. We eat the rough white bread. It is strange to eat the same things over and over again. It is a discipline in its way. It is not that we dislike this new, narrow range of satisfactions: on the contrary, the idea of eating at a wider scope begins to seem more and more grotesque. How could we ever have eaten curry one night and enchiladas the next? How could we have eaten chillies and chocolate bars and pancakes and wonton in the same twenty-four hours? Our promiscuity amazes us; our bodies remember by its absence the feeling of being thronged, of moving between hemispheres and time zones in the pause between breakfast and lunch, of being overrun, a hub of transient sensations like an airport terminal. It all seems now to have added up to a gluttonous neutrality, this specifying hunger that must select its object from the whole world. The discipline of our new regime is that of dissociating hunger from choice. Now there is only hunger, with sheep's milk cheese and tomatoes to satisfy it. It is important to be satisfied by what is known to you. Is that not a basic truth, biblical like the olive tree? But what of the desire to experiment, to roam,

to know the whole of life in your allotted portion of it?

The Italians have an answer for that. It is

gelato

. In

gelato

the writ of choice runs free. Facing the refrigerated counter of the

gelateria

you are harried by choice, vexed and tormented by the power to select until you nearly beg for it to be taken from your hands. Everywhere I see people eating ice creams, children and old women, stringy teenagers and burly men in business suits, beautiful

donne

strolling down the smart Arezzo streets at four o'clock licking cones laden with

nocciole

. The oral neurosis of the Italians appears to deposit the whole of its weight in this realm of frozen childhood pleasure. Once, in a

gelateria

in the middle of Rome, I saw a man rush in from the street, where his limousine remained parked on a double yellow line, and order the biggest ice cream I have ever seen. He laid his leather briefcase on the counter and carefully spread a paper napkin over the front of his double-breasted suit. Then he applied himself with an extraordinary, determined rapacity to the heaped-up mountain, diminishing it with great bites like a giant and looking at his watch after each one, while his chauffeur sat outside and stared through the windscreen. This was an entirely private transaction, it was clear. I remember noticing that the outermost peaks and ridges of the ice cream remained erect and frozen around the bitten-out voids, so quickly did the whole thing occur. Usually it is not possible to eat an ice cream quite so destructively. The mound begins to thaw and lose its definition: it becomes transitive, passing from object to subject, until it wears the marks of irreversible ownership and gives itself up entirely to the passion of the human mouth. Sometimes the children mismanage this transaction. They work away at one side of the ice cream while the other languishes, collapsing into landslides and milky rivers that run across their clutching fingers. Or they dislodge the whole ball with the first contact of their tongues, and it falls to the pavement with an abortive splat.

The display at the

gelateria

is an artist's palette that awakens deep urges and anxieties, for it asks that something be created

without hinting at the form it might take. Each colour has its own significance, but it is sufficient unto itself. What human mood is ever so monochromatic, so pure? And how can one choose without transgressing the truth of one's own fundamental ambivalence? I notice that the children do not suffer from this difficulty. They are monotheistic: they choose the same thing over and over again. But the adults experience a distinct anxiety at the

gelateria

, which is the fear of misrepresenting their own desires. There are some people who regard this inexactitude in a detached way: they are slow to blame themselves for choosing what did not suit them. They are interested in what they have chosen, up to a point, but if the

pistacchio

is less delicious than the

cioccolata

they had yesterday, then that is the fault of the

pistacchio

. It is nothing to do with them. But there are others who take these things more personally. They must choose the right thing: they strain after the prestige of premeditated satisfaction. Some people are more easily made unhappy than others, that much is clear. Often I do not eat a

gelato

. I sit at a table while the others choose, and think about something else.

There is coconut and hazelnut and pistachio. There is grapefruit, lemon, lime and mint. There is strawberry and raspberry and blackberry. There is

bacio

, kiss-flavour, an ice cream made of the Italian foil-wrapped chocolates whose infinite availability is a point of national pride. There is

straticella

, a streaky white inflected substance that causes me to feel a strange constriction of the lungs. There is nougat. There is

zuppa inglese

, a flavour so surreal that it seems to belong in a

gelateria

of the subconscious, a place where the artist's palette has given rise to whole sense memories and the ice creams have names like âSummertime' or âMy First Day at School'.

Zuppa inglese

translates as âEnglish Soup'. Apparently it is based on the recipe for sherry trifle.

One day we have lunch with Jim and Tiziana. It is Friday, and the restaurant in the village has fresh clams. Every Friday they serve

spaghetti alle vongole

and crowds of people come.

The car park is full of lorries. The drivers sit alone, each at his own table. They are young men, clean-looking and disciplined. They gather like novitiates for the sacrament. I have seen these same types of men pull to the side of the road near Arezzo, where wan-looking girls in scanty clothes wait, hugging themselves with their arms. I have seen the cab door open and the girls clamber up, showing their underwear and their bare bruised legs, their spike-heeled shoes. The lorry drivers sit at their tables, clean and correct, while the waitress brings the dishes. She too is correct, reverent, as silent as an acolyte. She wears her shining hair in a plait down her back.

Tiziana has been learning English. She has just returned from her class in Città di Castello, where she goes twice a week as a form of obeisance to Jim. She does not perform this romantic duty with good grace. She resents it: it gnaws at her pride, to be reduced to reticence, for she does not find the English tongue congenial. It is not she, Tiziana, who is at fault: after all, her Spanish is fluent and her French is not bad. No, it is the language of the English that is to blame. It is an ugly language, indelicate, stodgy, filling the mouth with its cloying, indigestible sounds.

Th-th-th

, she says, grimacing as if she were being strangled. That

th

is enough to choke you. She is surprised the English don't choke on their own tongues. Jim begins to speak to us in English and Tiziana folds her arms and puts her nose in the air.

Blah blah blah

, she says loudly, after a while.

Blah blah blah blah blah

.

Th-th-th-th

.

The food comes. Tiziana eats little of hers. She cannot eat. Her mouth is still full of that English stodge. Jim remonstrates with her. It's a waste to leave so much food. She should have ordered half a portion. Now he'll have to pay for a whole plate of wasted food. Tiziana looks at him with narrowed eyes.

Sco

teesh

, she says disgustedly.

I try to console Tiziana with my Italian. I say that I too feel humbled, feel childlike and impotent. It is hard to feel so primitive, so stupid. At this Tiziana looks exultant. Yes, she says, Italian is very sophisticated. It is the most sophisticated language

in the world. It is very complicated and beautiful. English is not complicated. That is why it is difficult for an Italian to express herself in English. An English person could never learn all the words there are in Italian. Look at Jim, she says. He has lived here for twelve years and his Italian is

una

merda

. But the English expect everyone to use their language. They will never understand the intricate mysteries of other tongues. They will never surrender themselves to the beauty of what is foreign to them. Instead they have to make an empire. Instead we all have to choke on English stodge.

The

spaghetti alle vongole

is so delicious that it has a kind of holiness about it. Trained as we now are on sheep's milk cheese and white Italian flour, purged of our promiscuous tastes, we are capable of understanding it. It is our prize, our reward, this understanding. A pile of empty clam-shells remains on my plate like the integuments of a poem whose meaning I have finally teased out. Afterwards Jim says he's going home to watch the French Open. Tiziana will not come with him. She declares her intention of going to look up an old friend in Sansepulcro. She is petulant and overwrought. In the car park Jim says goodbye to her. He is grim around the mouth. But a few days later we meet them in Gianfranco's and they seem excited, almost delirious. Tiziana is dolled up in a tiny skirt and high-heeled shoes. She flashes her eyes exultingly as Jim drags her up and down the aisles by her hand. Jim has a kind of charged resignation about him. They are buying steaks. Gianfranco has fantastic steaks, Jim says, with his best Dundee certitude. They're top-quality steaks, he repeats, so hang the expense.

Not Scoteesh

says Tiziana, winking her fronded eye. She giggles as Jim drags her away again by the hand. We continue our slow progress along the aisles, patiently piecing together our diet as we piece together our Italian sentences, while Gianfranco waits behind his counter to pat the children on their heads and ask us how we are enjoying our long

vacanza

.

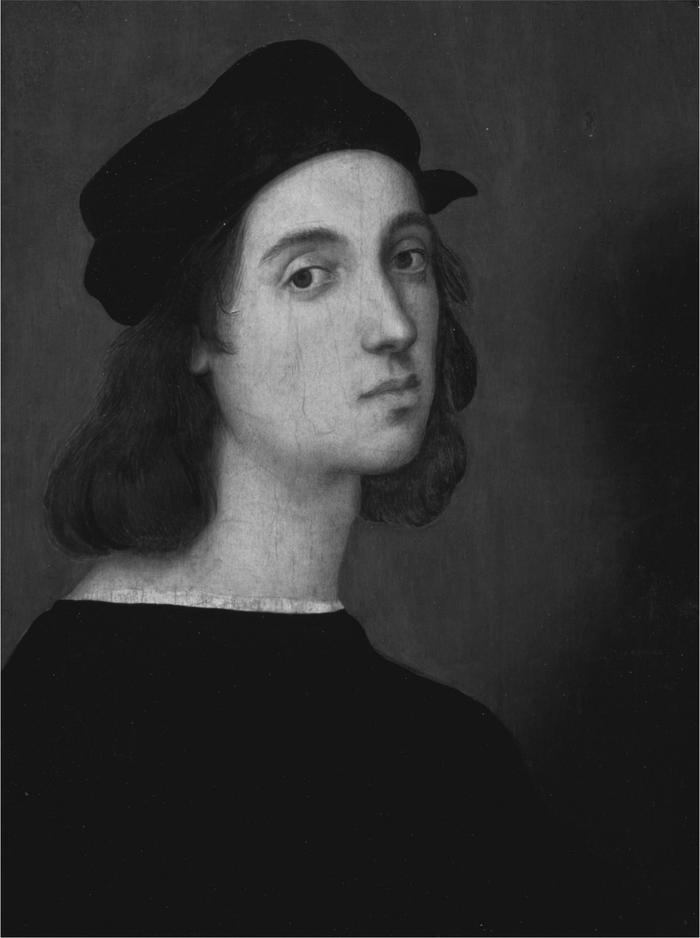

Vasari has the following to say about Raphael Sanzio, born in Urbino in 1483:

With wonderful indulgence and generosity heaven sometimes showers upon a single person from its rich and inexhaustible treasures all the favours and precious gifts that are usually shared, over the years, among a great many people. This was clearly the case with Raphael Sanzio of Urbino … Nature sent Raphael into the world after it had been vanquished by the art of Michelangelo and was ready, through Raphael, to be vanquished by character as well. Indeed, until Raphael most artists had in their temperament a touch of uncouthness and even madness that made them outlandish and eccentric; the dark shadows of vice were often more evident in their lives than the shining light of the virtues that can make men immortal.

Raphael was the only child of a painter, Giovanni Santi, a man whose own rough upbringing had both lamed his talents and refined his humanity. Perhaps this is what Vasari means when he describes the meting out of heaven’s gifts. Must the need to live and the need to create be fed from the same allotted share? Thus the artist is uncouth, or mad; and the man who chooses to be good will rarely have enough left over to fund his visions, unless he had the luck to enter this world undamaged. This was Raphael’s position. Vasari notes that Giovanni refused to send his baby son out to be wet-nursed. Instead Raphael spent

his infancy and childhood at home, with his parents. Giovanni taught him how to paint, and when he had ascertained the extent of his son’s talents he set out to find a great artist to whom he could apprentice him.

The pre-eminent painter of that period was reputed to be Perugino, and so it was to Perugia that Giovanni took himself, to cultivate the friendship of the man whose powerful brand of parochialism is so aptly expressed in the name by which he became known. Perugino was an egotist-innovator of the Cimabue type; and just as Cimabue’s fame was eclipsed by that of his pupil, Giotto, so Perugino’s art was fated to become a pleasant suburb of Raphael’s. Shortly after brokering the apprenticeship of his eleven-year-old son, Giovanni died. Raphael left Urbino and the world of his childhood, and went to Perugia to embark on a second childhood with a second father, whose self-portrait in Perugia’s chamber of commerce bears the legend: ‘Behold Perugino, the greatest painter Italy has ever known.’

The sweetness of Raphael’s disposition is often mentioned by art critics. It is offered as the explanation for many things: his popularity with influential patrons, his humility, the timbre of the paintings themselves, with their devotional secularism, their innocent-seeming love. Vasari, with his trademark enthusiasm, believed that Raphael’s gifts of ‘the finest qualities of mind accompanied by grace, industry, looks, modesty and excellence of character’ raised him above the sphere of men and into that of ‘mortal gods … who leave on earth an honoured name in the annals of fame [and] may also hope to enjoy in heaven a just reward for their work and talent’.

It is a little curious, this fêting of the virtuous artist. Like Mozart’s, Raphael’s art resolves itself in the childlike love of life: this is the harmonic home from which the world is investigated and to which the art is always striving to return. There are no scars in Raphael’s art. There is none of the phallic aggression of Michelangelo, the worldliness of Titian, the tragic knowledge of Tintoretto. In short, there is no dimension of experience: everything

is seen as if for the first time, is lived before our eyes, and sweetly remarked on. How relieving, to arrive at art by the route of pure sensibility! How pleasant, to look at Raphael’s fond Madonnas and playful Christs and see only happy recollection there, not doomed foreknowledge!

When Raphael went to live with Perugino, his work consisted of filling in parts of Perugino’s large frescoes on the master’s behalf. Raphael was adept at this: indeed, he soon became better at painting Peruginos than Perugino himself. Raphael made copies of his master’s work that could not be told apart from the originals. And, as Vasari puts it, ‘it was also impossible to distinguish clearly between Raphael’s own original works and Perugino’s.’ Raphael, it seems, was a little

too

sweet natured. Where was his artist’s ego, his vanity? Was he so well brought-up, so couth, that he broke his own chip of genius in two and shared it? One day Perugino went off to Florence on business and Raphael went to visit Città di Castello with some friends. While he was there he did one or two paintings in local churches, in his Perugino style. They would certainly have been mistaken for the real thing had he not signed them himself: as it was, the imitations brought Raphael immediate fame. He was invited to Siena to do some decorations in the library, and while he was there he heard a group of painters discussing the current rivalry between Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, and the great works with which they were attempting to outdo one another in Florence. Raphael immediately stopped what he was doing and went to Florence. The sight of Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s paintings woke him from his religion of Perugino. Yet how would this awakening express itself? Would he merely subsume himself in one artist after another? And their paintings were so anatomical, so mortal, so charged with emotion: how could Raphael, the obedient child, the ventriloquist, compete with these phallic male giants?

He returned to Perugia, where in the monastery of San Severino he painted a fresco and signed it, as Vasari says, in ‘big, very legible letters’. Then he went back to Florence and in the

space of three years painted a large quantity of Madonnas and other works for Florentine patrons. He painted the

Madonna

of the Meadows

and the

Madonna of the Goldfinch

. He painted a portrait of Angelo Doni, a wealthy Florentine wool merchant, and of Angelo’s wife Maddalena, in the style of Leonardo’s

Mona Lisa

. Yet in spite of his popularity and his ceaseless flow of commissions, his artistic ‘awakening’ and his newly declamatory signature, his good looks and his amiable personality, Raphael remained locked out of the reality his contemporaries were charting like a newly discovered continent. What were they seeing? What did they know? And how could he come to know it too? For Raphael’s Madonnas were just sweet, beautiful recollections of childhood, and his portrait of Maddalena, though he worked and worked on her hands and her clothing to make her human, lacked what is more human still, what is invisible to the naked eye. It lacked the very thing that makes the

Mona Lisa

seem to smile: mystery.

*

The train to Florence passes through tunnel after tunnel, long interludes of darkness that suddenly give way to bright, bleached passages of intricate daylight, just as dark tunnels of sleep seem to snake their way towards dreams, bursting into colour and detail and then plunging back into a swift-running obscurity. The hot, dusty vineyards of Chianti flash past; here and there a house stands remotely in the hills. Then we are in a tunnel again, travelling without seeming to move, thundering at a black standstill with a clamour that might break open time itself. And indeed the time machine of popular imagination never actually stirs. It merely gathers in intensity, as though an effort of will is all that is required to enter the past. I don’t suppose this idea has anything to do with looking at paintings, but the procedure is the same. It is a matter of intensity, of will. It is possible to look at a painting and not see anything at all. There must be an offering of the self before the painting will open. There must be intensity, or the past will stay locked.

Florence station is slightly seedy, with the scummy froth of litter and souvenir stalls and fast-food places that is the residue left by tourist tides that sweep ceaselessly across its reef of treasures. In the city there are people everywhere: they form great winding queues, like roads whose destination lies out of sight. Several times I see people automatically joining them, apparently without knowing where they will lead. There are Japanese and Germans and French, Spanish and Dutch and American. They drift around the city in concertinaing herds, their guide at the front like a shepherd. The guides hold sticks raised in the air. Each one has a flag or a brightly coloured ribbon tied at the top. Their flock wears the same ribbon, so as to be identifiable in the crowds. There is a group with yellow ribbons tied around their throats. There is a group with tartan caps. It is like a strange medieval pageant or festival. They flow and counter-flow in the variegated spaces, each one drifting out and contracting like a single, liquid creature. They bunch up in alleyways and fan out over the piazzas; they wind like serpents along the crowded pavements. They congregate at Ghiberti’s

Gates of Paradise

and the guides shout across one another in their different languages.

It is very hot in the city. The buildings stand in dusty chasms of shadow and light. The traffic crawls along the Via della Scala. The blue sky is far off and remote. The Piazza del Duomo is a crucible of glare, with its white marble tower and cathedral and baptistery. The crowds look half-calcified in the bleaching light: in their individuation they seem to be helplessly disintegrating, breaking down into smaller and smaller units. We move along a congested alleyway towards the Piazza della Signoria, where a riot of cafe terraces and horse-drawn tourist carriages and pavement hawkers selling African jewellery is underway. People push and shove rudely, trying to get what they want: photographs, food, a tea towel bearing the cock and balls of Michelangelo’s

David

. There are so many people that the sculptures on their plinths in the Loggia dei Lanzi seem truly to be the gods they represent, gazing down on

the awful spectacle of mortality. I have seen a fifteenth-century painting of the Piazza della Signoria, where children play and the burghers of Florence stroll and chat in its gracious spaces, while the monk Savonarola is burned at the stake in the background outside the Palazzo Vecchio. Here and there peasants carry bundles of twigs, to put on the fire. Now our violence is diffuse, generalised: it has been broken down until it covers everything in a fine film, like dust.

The long, colonnaded facade of the Galleria degli Uffizi stands in a side street, between the piazza and the River Arno. It is as shady and civilised as an arbour here, despite the queue that runs four or five people deep all down one side and up the other. The light from the water is soothing, mesmerising, on the high-up windows. The people in the queue have an eternal look about them, for only a small number are admitted every hour. The gallery is visited by appointment: there is a separate door for people with tickets. A young man in a dark, immaculate suit stands there, bowing and ushering the ticket-holders in without delay. The people in the queue look on from behind their ropes. They will be there for ever. They are bound into a thick, hot cable of bodies that runs as far as the eye can see. There are people with children, people with large suitcases. Again and again, those with tickets arrive and are whisked into the cool interior before their eyes. We ourselves have tickets: we had to wait two weeks for our appointment. How sparse the world’s treasures are! And how hungry, devouring hour after hour of life! It is almost as if they wish nothing more to be created.

Inside, the building is deep and tenebrous and hushed. We go up a great stone staircase, rising through layers of light, past fragments of Roman sarcophagi leaping with mythical creatures, past cracked marble torsos and far-seeing Hellenistic faces, up and up as though we were rising through time itself. At the top there are long galleries like avenues, filled with an unearthly, watery light. Far below the river can be seen, broad and fertile and opaque. It is like a strange kind of heaven up

here, where sculpted gods and goddesses stand along the walls as though milling in the halls of eternity. They are so well guarded, so secure in their possession, so superior to the dusty streets below, teeming with life. I remember the people queuing downstairs, held like waters at a dam. What pent-up force waits there? What do they want? Why do they accept the authority of this heaven, and their banishment from it? Yet it is true that all those people couldn’t fit up here comfortably. I don’t suppose we would worry about comfort if it were left up to us. The yearning for beauty has not surrendered entirely to the desire to be comfortable, that much is clear. An overgrown humanity trying to fit into the narrow, beautiful past, like a person in corpulent middle age trying to squeeze into a slender garment from their youth.

We pass through the rooms, past Cimabue and Giotto, past Simone Martini’s Annunciation that seems spun from a cloud of gold. This is the old world, where man is unfolding as though from a bud, by increments. Simone’s Madonna draws her cloak around her throat, while with her other hand she marks her place in her book with her thumb. Nearby, Lorenzetti’s Christ-child grips the Madonna’s chin, his fingers at her mouth. Slowly, awareness comes. The figures begin to look out of the paintings, out into the world. Fantasy and reality succeed one another in waves, going forward and then back and then forward again, but always climbing, encroaching on some imperceptible common goal. The Madonnas change, the Christs change, the saints acquire different faces. Then there is Leonardo’s Annunciation and the Madonna becomes Mary, a girl of flesh and blood. Perugino’s Christ in the garden at Gethsemane is a good-looking young man with a fresh, sensitive face. In Mantegna’s Circumcision two women stand talking in asides, slouching; one of them rests her arm on her own stomach, as women do when they aren’t self-conscious, while her other hand abstractedly touches the hair of the little boy who stands beside her. Suddenly we are on the firm footing of life, though the subjects have barely altered. We have arrived at the

grandeur of the human. By the time we reach Correggio’s

Ado

ration of the Child

, Mary looks like what she is: a real woman who has put on a blue cloak in order to pose for the artist.

Self Portrait,

c

.1506 (tempera on wood) by Raphael