The Last Supper (14 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

There is a self-portrait by Raphael in the Uffizi. It is a strange painting, of a frail, wistful-looking youth clad in black. It is faintly ascetic, even depressive: it is a portrait of Raphael’s

captive ego. Nearby hangs the

Madonna of the Goldfinch

. It was damaged in the mid-sixteenth century, when the house of Lorenzo Nasi, who owned it, was destroyed in a landslide. Carefully it was pieced back together, but a long, sad scar runs through it, all the way down the virgin’s breast and belly and lap. Shortly after he painted the

Madonna of the Goldfinch

, Raphael’s mother died. The woman in the painting is neither real nor divine: she is an emotion, a flesh-memory. The Christ-child leans back against her knees, his small foot resting on her larger one, his head tilted back into her lap. The other child, St John, is holding the goldfinch. He is showing the bird excitedly to the Christ-child and the Christ-child is reaching out half-heartedly to touch its head, gazing at his friend with sorrowful, almost baleful eyes. He won’t stray one inch from his mother to touch the bird. He has wedged himself between her knees. It is John who holds the bird, and it is John the Virgin looks at from her downcast eyes. It is John on whose bare shoulder her fingers rest.

Madonna of the Goldfinch

,

c.

1506 (oil on panel) by Raphael

Michelangelo’s

Tondo Doni

(

Holy Family with the Young

Saint John

) hangs close to the

Madonna of the Goldfinch

. Michelangelo’s attitude to the male competitor John is clear. He has put him in the background, behind a wall with the rest of lesser mankind; a respectful urchin in an animal skin who gazes up, lost in admiration for the hero of the hour, the vigorous Christ who is seen clambering naked from his father’s lap over the form of his mother and clutching her hair for balance. Mary has her arms outstretched to receive him, but it is far from clear that she is his destination. He looks as though he means to climb out of the picture and head off into the world to collect his due. He balances on top of his parents, the absolute egotist, crushing them underfoot and flashing his virility as he goes. This was perhaps the first time the Christ-child was depicted towering over the Madonna, a lithe lass with a husband too old and too cautious for her. This son already owns his mother. She reaches for him while Joseph hovers, grey haired and anxious, but she cannot possess him. He has already escaped his parents. He wears a band of victory in his hair, his only adornment.

*

In 1509 Raphael left Florence and went to Rome. A distant relation of his, Bramante of Urbino, was working for Pope Julius II and had persuaded him to commission Raphael to

decorate a series of rooms that had just been added to the papal apartments. Raphael went straight away, and when he arrived at the Vatican found numerous artists at work there, including Michelangelo. Raphael was given a lot of work to do, and for everything he did he received the highest praise. But praise has its own limits. The question of rivalry, which had dogged Raphael, though he had repressed it by a mixture of imitation and charm, now came to torment him face to face. Pope Julius admired Raphael, but it was Michelangelo he loved, Michelangelo he fought with and banished and begged to come back, Michelangelo who rebelled and was somehow loved the more for it. This passion of patron and artist found its best expression in Pope Julius’s desire for Michelangelo to sculpt his tomb. He had a drawbridge built between his room and Michelangelo’s, so that he could come and go as he wanted, and inspect the progress of his memorial. Raphael had never experienced this desperate, exacting kind of love. In art he was the lover, the aspirant, not the beloved. He was the one who hoped to please. But was there something else, a serpent, a secret desire to be first and best that masked itself in his humility? And was it in fact this mask that formed the blockage in Raphael’s art, its stubborn separation from reality? There is jealousy in the

Madonna of the Goldfinch

, but there is neediness too. Raphael needed something: but what? Michelangelo went around having fist-fights and feuds with people, and dreamed of making giant statues in the Carrera quarries to leave behind him, as the ancients had. All he seemed to need were blocks of marble big enough for his ambitions, and the freedom to carve them. How was Raphael to go about satisfying his own unacknowledged need for greatness?

While Michelangelo was out of Rome, Bramante and Raphael set about trying to undermine his reputation. They suggested to Julius that to build his own tomb was to invite his own death. When Michelangelo returned, he was told by Julius that work on the tomb was to be suspended. Instead, he was to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, a job at which

Raphael and Bramante were confident he would fail, for Michelangelo was principally a sculptor, not a painter. Michelangelo locked himself into the Sistine Chapel: no one was allowed in, not even Julius. It seemed that to fetter Michelangelo was simply to make his myth the more powerful. Soon, all of Rome was fixated by the mystery of what lay behind that locked door. Then, according to Vasari, Michelangelo had to leave Rome for a few days, and while he was away Bramante got hold of the keys. He and Raphael went in to look. And what they saw, of course, was the pre-eminent artistic achievement of the Renaissance and perhaps of the whole history of art, past, present and future.

Seeing the Sistine Chapel, Raphael experienced the overwhelming reaction of his primal reflex, imitation. He immediately went and repainted whole parts of his own work in the Stanza della Segnatura in the style of Michelangelo. After the cataclysm and shame of rivalry, he retreated behind the mask of humility, never to come out again. With the world’s greatest painter as his template, he became a far better artist. And to the art critic’s eye he had gained far more than he lost, for in the end his borrowing of such greatness amounted to greatness itself. Not everyone who sees a Michelangelo can go off and paint a Michelangelo. Raphael was almost as good at painting Michelangelos as Michelangelo himself. His captive sensibility needed a love object to express itself. It is in this, perhaps, that the critic perceives what appears to be Raphael’s sweet disposition. They see it as humility, not the devious workings of a repressed ego. They see it as a tribute, not a theft. But Michelangelo saw it as a theft.

*

Raphael died young, at thirty-seven. He was, Vasari says, ‘a very amorous man with a great fondness for women whom he was always anxious to serve’. His passions were more powerful in the sexual transaction than in the artistic, for in sex there is reciprocity. The love is not praised: it is returned. This, it is clear, was a compelling experience for Raphael. Perhaps, like

the Christ-child in the

Madonna of the Goldfinch

, constant bodily contact with a woman, in other words his mother, was his way of seeing off the male competitor, who could not dislodge him physically even if he stole her attention in other ways. On one occasion, he was so besotted with a woman that he was unable to concentrate on the work he had undertaken painting the loggia of Agostino Chigi’s Villa Farnesina until she was installed there with him.

When Raphael first went to Florence as a youth, in his Perugino years, it was Leonardo da Vinci who initially attracted his succubus-like notice. Leonardo’s women were so beautiful: the inclination of their heads, their soft, sympathetic expressions, their golden atmosphere of smiling female mystery. Straight away Raphael’s Madonnas began to smile too, and incline their golden heads. The

Madonna del Granduca

, painted in 1505, emerges out of darkness like a figure in a dream, or like the love object emerging for the first time from her anonymity. She holds the Christ-child upright against her side, and yet it is he who appears to be holding her. One hand rests proprietorially on her bosom, the other on her neck. He looks out into the eyes of the world, displaying her and owning her, this woman he has brought out of the shadows and whom he seems to grip lest she recede again. Later, when he was painting Agostino Chigi’s loggia in Rome, Raphael was asked where on earth he had found his model for the nymph Galatea. She was so beautiful: how could she possibly exist? Raphael replied that she wasn’t painted from a specific model. She came from an idea he had in his own mind. It was, of course, here in the Villa Farnesina that Raphael’s mistress was now living with the purpose of oiling the wheels of his refractory genius. Did the presence of the real woman permit the ideal woman to be imagined? Or was this mistress, in fact, the living model of Galatea’s wondrous beauty whom Raphael, the possessive child, denied and hid away from other men?

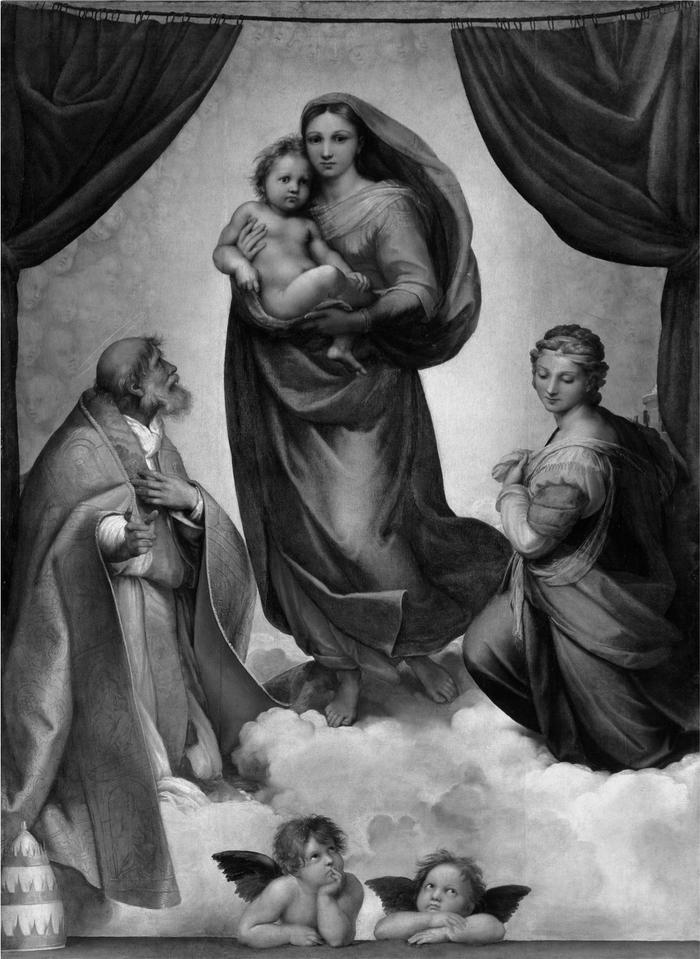

The

Sistine Madonna

, 1513 (oil on canvas) by Raphael

Raphael’s friend Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi, who found the painter’s promiscuous behaviour disturbing, believed that marriage would be the answer to Raphael’s problems. Here Raphael encountered a rare and insurmountable certainty in himself: he did not want to get married. Perhaps, after all, the ideal woman, the Madonna, could not be conflated with the sexualised woman, the courtesan or mistress. But it was in the

function of Raphael’s devious ego to give the appearance of being dominated and directed by other men: always, it was by this route that his true desires became known to him. In this case, however, the directive and the desire were mutually hostile. Typically, Raphael decided that what he wanted was not to get married but to be a cardinal, like his friend. Pope Julius was dead by now, and Pope Leo, a great patron of Raphael’s, had in fact insinuated that Raphael might receive the ‘red hat’ once he had finished the hall he was painting. But Cardinal Dovizi had meanwhile elicited Raphael’s promise to marry his niece. Imitation and obedience collided: he couldn’t be a cardinal

and

get married. And in the prospect of marriage Raphael appeared to glimpse the frontier of his civilised self, beyond which lay the undiscovered hinterland of his true nature which he had never dared to enter. How can an artist attain greatness if he never knows the truth about himself? In the same way, I suppose, that a blind man can see the world, because people describe it to him. He refines his other senses. He learns to recognise the truth, even if he can’t personally see it.

Raphael responded to his dilemma by pursuing his pleasures, as Vasari puts it, ‘with no sense of moderation’. He contracted syphilis and became very ill, but because he concealed from the doctors the cause and nature of his illness they diagnosed him with heat-stroke and proceeded to bleed him. From this last piece of self-deception, Raphael died, in 1520.

*

The

Sistine Madonna

, which Raphael painted in 1513, shows a rather different mother and son than the golden women and possessive boys of his earlier years. This mother is smaller, more lifelike, less dominating. The boy is larger and more confident. He is beautiful, with lustrous hair and a lithe, well-modelled body. He does not clutch or grip his mother. He reclines in her arms, one leg crossed at the knee, like a young man sitting easily in an armchair. He seems satisfied. Only his head, which rests unconsciously against her cheek, betrays the fact that she remains his object, his desire. For a moment he

looks as if he might be getting up and going somewhere, but that resting head says it isn’t so. He is more relaxed, that’s all. The woman is more real to him. She isn’t a golden ideal he fears will be stolen from him. He doesn’t cling on to her. His hand lies lightly on his own leg. It is she who holds him, supports him, of her own volition.

Portraits of Leo X (1475–1521) Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi and Giulio de Medici (1478–1534) 1518 (oil on panel) by Raphael