The Last Supper (21 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

The children want to go to the beach club – their new friends have told them all about it. Apparently, the hotel has a private beach, directly below. This is where the Americans have been spending their days. The two sets of children cling on to one another, as though we might attempt to tear them asunder. The Americans have been on the road almost as long as we have, far from the society of other English-speaking children, and all four girls have the hunger of émigrés for the forsaken world, the world of friendship. It is as though they have encountered fellow citizens from the homeland, the old country. Girls their own age! A whole familiar, vanished way of life is suddenly present to them once more, with its particular references and language and atmosphere. They want to speak it, this language; they want to reminisce; they want to go to the beach club.

The Americans ask when we are leaving. Earlier, the man at the desk told us gravely that we were free to stay all day and make use of every hotel facility, but this offering does not satisfy the Americans. I watch them weigh it up, the day and its profits: they had been planning to go to Portofino for lunch. It is not a sound investment, their relationship with us. There are no long-term dividends. They are disappointed, almost angry. Our stock has no value: a measly day is all it’s worth. The father is inclined to jettison us straight away. He wants to go to Portofino, as agreed. Instantly his daughters are distraught, almost tearful: they have a white, strained look about them that causes my own children to fall silent and gaze at them

anxiously. The mother speaks. She is unemotional: she seems to stand in great desolate prairies of neutrality. She says that they will go to Portofino later, at four o’clock. Until then, the girls are free to be at the beach club. At four o’clock she will expect them to come without being told. She herself is going to go and lie down. She goes, and we are left with the father. There is only one thing for it: we offer to take charge of the children, and return them to the hotel at four. He nods curtly. He has got a good deal after all. Desire has been swabbed away from him: sponge-like, we have absorbed the embarrassment of the whole situation. He walks slowly back to his table and picks up his copy of the

Herald Tribune

.

At the beach club there is a marine trampoline, riding out on the waves. The sea is ebullient, after the storm. All day the children swim out, and are dashed deliriously back on to the beach. They bounce madly on the trampoline. They have funny conversations, which I overhear in fragments from behind the cover of my book. The Americans have a friend in England called Sophie. Do we know her? I hear my daughter talking about her best friend Milly. Do they know Milly? She’s so nice.

Later I hear the American girls talking about their mother. She’s really sick, the older one says. I sit up: I want to explain to my daughters what that means. I want them to be kind. They are sitting in a row on the shoreline in their swimming costumes. Sometimes a wave comes up and foams at their feet. They are tossing pebbles into the water. I buy them an ice cream. I leave them be.

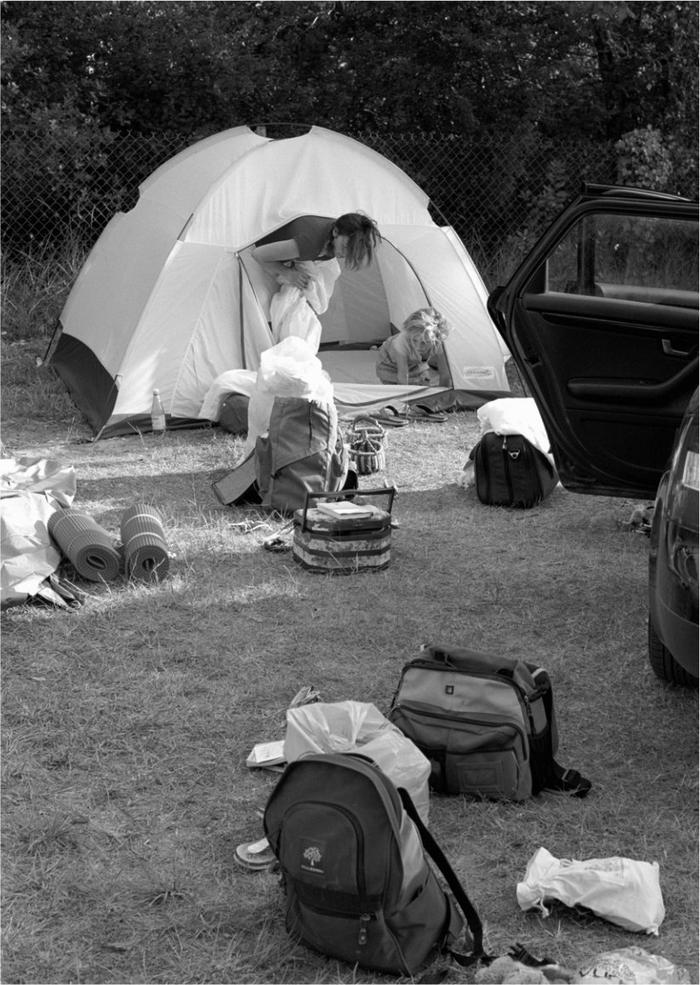

At Ventimiglia, near the French border, we turn off the coast road and drive up into the hills. We are looking for somewhere to pitch Tiziana’s tent. It is six o’clock, still hot. The countryside is a little ragged, scarred here and there with enterprise, and with the formlessness of frontier places where the feeling of identity comes in unpredictable surges and then frays again, like an unravelling hem. The road goes up and up. We pass parked lorries and derelict roadside restaurants, travel through villages that cling along the verges and then peter out. The irresolute green vista resumes hesitantly, after each pause. We reach Dolceacqua and the broad brown Nervia river. There is a feeling here of civilisation and abandonment, of something dead that was once alive: the ruined castle on its hill, the ancient arc of the great stone bridge, the tall, narrow, ravaged-looking terraces. Everywhere there are vineyards, modernised, bristling with signs. We stop and ask the way to the campsite, and are directed on ahead.

At last the campsite appears, a modest roadside place in its obscurity of low hills, where nonetheless there are people, established in their dusty pitches beneath the trees as though they had lived there all their lives. There are some mobile homes, where washing hangs on lines and television sets flicker through the windows. There are Dutch tents and German tents and tiny pod-like tents with bicycles parked outside. There is a little bar and a cafe, and next to that a small rectangular swimming pool. The sky is overcast and grey: the dingy pool is full of children, whose parents sit in white plastic chairs

on the concrete tiles. It is slightly desolate, this arrangement, though everyone seems to accept it. The countryside extends indifferently around; the sky is moody overhead; the parents lie torpid in their chairs, or rouse themselves to sudden, startling fits of activity, plunging heavily in and hurling their offspring shrieking across the water. Shortly after we arrive, everyone abandons the swimming pool and returns to their tents. It is no longer hot, but we will swim in any case. In the traffic jams of Ventimiglia, where we crawled through the dusty, constricted streets of the

città vecchia

behind giant lorries bound for Nice and Marseilles, the sun was cruel and adversarial, faintly humiliating: it was a form of oppression, from which swimming offered the only possibility of liberation. But we could find no road down to the sea at Ventimiglia, and in the end the heat passed, undefied. We defy it now, in retrospect, circulating around the cloudy water where children’s blow-up toys drift, forgotten, across the surface beneath the grey sky. Desire and satisfaction have become uncoupled. There will be no consummation tonight. There will be no resolution, no declaration of the day’s victory, no enshrining of its significance. We have re-entered the other reality. We have returned to the ordinary, unexamined experience of life.

We pitch our tent on a dirt terrace in the trees, between two other tents. Everything is silent. People walk to and fro, commuting to the sinks and the shower block. Their flip-flops slap against the soles of their feet as they pass. They carry washbags, dirty dishes, boxes of detergent. They glance at us beside our tent. When we ourselves walk to the shower block, the people by their tents glance at us. It has grown dark, though we were not aware of the sun setting. The light drained unremarked from the wadded sky with its screen of hills, and left behind an arid darkness. We go to the bar, which is empty. After a while a man comes through, and we ask if there is anything to eat. He thinks there is not. He says that he will go and talk to his wife. The wife appears: they are not serving food, but she has cooked

spaghetti alla bolognese

for herself and her

husband. If we think that will be satisfactory then we are welcome to share it. She will serve it on the terrace by the swimming pool, with a bottle of wine from their vineyard.

We go out and sit on the terrace. There is no one there. The sky is full of stars. The pool is inky, inchoate, flecked with silver. It has soothed us, this encounter with the man and his wife, but it has aroused our emotions too. It has awoken our love for Italy just as we had entered the grey prospect of leaving it. We are nervous, a little shaky. We discuss our plans, the two nights that remain after this one before we catch the boat. I want to stay here, on this side of the border. I don’t care what the campsite is like. I don’t want to leave. The children run around in the dark. The woman brings our food in a big silver covered dish. She is worried it will not be enough, but when she takes off the cover we see that there is almost more than we can eat. Later the husband comes out to see how we are getting on, and when we praise the spaghetti he becomes eloquent, descanting gently in the starlight on the glories of his wife’s cooking as he clears the plates. This was our last supper: it was difficult to recognise it, to understand it, until it was complete. We go to our tent, and lie listening to dogs barking somewhere in the valley.

The next day we find ourselves in Dolceacqua, wandering aimlessly through its dark viscera of alleyways, where tiny doors lead up to dwellings of unimaginable exigence and dilapidation. In the sloping, deserted, pockmarked piazza the church bell is tolling. Through an open window high up in a crevice-like street I hear someone playing a song by The Cure. The river runs between its dry, dusty banks. We climb up to the ruined castle and stare into its blackened interior. Coming down, we take the wrong path and find ourselves in a car park surrounded by wire fences. It is too hot to go back up. We pass through a gap in the fence and down a steep, narrow stairway that twists and twists across a derelict, litter-strewn hillside. It leads to a kind of catacomb beneath the village, a dank network of tunnels and passages where we stoop

beneath the low ceilings, searching for a way out. Suddenly we are tired of being here. Here is where we neither want nor have to be. It is one or the other, duty or desire, freedom or responsibility. That is the pendulum swing, the inescapable arc of life. But this place we have the power to leave.

We go back and pack up the tent. The pool is full of children again. Their parents sit prostrated in their white plastic chairs. There is the sound of splashing water, and of people calling to one another in German. At four o’clock we are on the road down to Ventimiglia. We take the exit to Nice, fly through a checkpoint where a traffic policeman in a beautiful uniform waves us on with his white gloves, and enter a tunnel that passes straight through a hillside into France. We come out, blinking, in the bleached light of the Côte d’Azur. It is strange, that the violence of leaving Italy should occur without sensation. It was a single blow, swift and numbing, virtually painless. But when we stop to get petrol and water outside Nice, I feel a nameless sense of bereavement. The French words are uncomfortable in my mouth. The girl behind the till is busy, distracted, sullen. I stand before her; I feel that I have something in my hands, something large and shimmering and important, something I am aching to give. There are people behind me in the queue. They are impatient; this is a big place on a hot motorway where needs are processed without sentiment. But sentiment is what I require; I require feeling, acknowledgement, kindness. I ask whether they sell road maps – we have lost ours. She doesn’t hear me, so I ask again. This time she understands. She is incredulous, disgusted: it is outrageous, that I have asked her such a question. It is as if I have robbed her of something. I am struck by the economy of her outrage. It takes a second, no more. She points to the shelves. Go and look, she says.

*

We can’t find a place to camp. We drive around the empty French countryside. It is late afternoon, the sky still and grey, torpid. Everything seems stunned, anaesthetised. We pass a place where little white houses made of corrugated tin rise in

rows up a denuded hillside. It is a holiday park. The man tells us they have an area for tents. He is tall and broad and ruddy, like a farmer, but one of his arms dangles shrunken and deformed from his shirtsleeve.

We go into his office, a wooden cabin that stands on a circle of gravel. He writes down our details using his good arm. While we are standing there a family come in. They are Dutch, a well-dressed couple and two fair-haired children. The father instantly starts to shout. He shouts in English. He is shouting at the top of his voice, at the manager of the holiday park, who continues carefully writing. After an interval, the manager looks up. The Dutchman is beside himself: cords of muscle stand out around his neck, and his pale eyes look as though they might fly out of their sockets. He is still shouting: his wife ushers their children outside. He shouts that they have been tricked, deceived, misled. The manager is a villain, a liar. They have come here all the way from Holland, all the way here for a two-week sojourn at the holiday park, and what do they find? I pay attention: I am interested to know what they have found. Despite his aggressive manner, I am even a little sympathetic. I expect him to say that what they found was a dump full of tin huts, instead of the Provençal idyll doubtlessly advertised. But he does not say that. He barks his accusation with a mouth rectangular with rage, like a letterbox. Its substance is that they have been given a different tin hut from the tin hut they booked at home, on the internet. But

monsieur

, the manager says with a shrug, the huts are all the same. At this the Dutchman screams.

I REFER TO THE POSITION OF THE

HUT! THE POSITION OF THE HUT IS INFERIOR

! A fusillade of expletives issues from his mouth. Suddenly I am afraid for the manager. I think the Dutchman is going to kill him. His anger is delinquent, bizarre. He is a narrow, colourless man, a suit. The manager, with his deformity, seems like someone he might choose as a victim. The manager rises from his chair: he is twice the Dutchman’s size. But he is somehow broken, wounded. He doesn’t seem to care whether the Dutchman kills him or

not. He has a withered arm; his holiday park

is

a dump. It would almost be better if that was what the Dutchman was angry about. He tells him to wait; he is going to show us where to put our tent. When he returns, he will see if he can rectify the problem. The Dutchman immediately stalks out of the cabin. Later we see him, standing on the gravel with his family. He is very upright, rigid, as though with the shock of his own significance. His face is white. He has a puny, triumphant air: he has been fobbed off, but he is telling himself that he acted like a man.

We follow the manager up a dirt road that zig-zags interminably through the white tin suburb and then comes out at the top on a stony ledge. The stony ledge is where we are permitted to pitch our tent. It is too late to argue: we put the tent up and get back in the car. It is nearly dark, and we need to find something to eat. There is a village a few kilometres away. When we get there we are surprised to find that it is packed with people. The centre is completely closed off. We park the car and walk. In the square a giant screen has been put up, and the buildings are all strung with flags. It is the World Cup final: France are playing Italy. The square is crowded, with old ladies and children, with gangs of kohl-eyed teenagers in black drainpipes and plump middle-aged couples. Everywhere there are shirt-sleeved delegations of men locked in endless, cheerful conference.

We find a seat, get beer and food from a stall. We feel a little treacherous, though our treachery is all against Italy. It is not this prosperous French village we are deceiving: we are sure that France will win. They

have

to win, for much the same reason that we had to leave Italy – because reality requires it. Anything else would be fantastical, improvident. The French have Zidane, rationality, form. These are the things on which expectations can be based and decisions reached. What do the Italians have? I remember the traffic policeman who stood at the mouth of the tunnel with his elaborate braided uniform, his long leather boots, his snowy gloves, his manner that was both theatrical and sincere. He courteously waved us out of his land

like an actor at the final curtain. The Italians have splendour. What would a decision be like that had splendour as its basis? To what strange, beautiful expectations would it give rise?

The French do not win the World Cup final. The Italians win. Zidane assaults one of the Italian players, butting him with his white, domed, rational forehead. We return to the rocky ledge, where all night the hard, uneven ground probes our slumber and sends our bodies roaming around the tent, searching for flat places, for relief.

*

We come off the motorway at St-Jean-d’Angély and skim through the silent, yellow-white landscape. The road is completely straight: it stretches on for as far as the eye can see, pale grey and empty. The children gaze through the open windows. They are very quiet. Now and again a straight line of trees passes, at right angles to the road, and their eyes flicker, mathematically registering the perspective. We have booked a room in a hotel: we arranged it by phone. Tiziana’s tent has been folded into its bag. It is our last night before England, a night for reflection, order, readiness. The world is once more flat and straight, symmetrical. It is bare and clean, blank, like paper. It seems to invite something, some final utterance. What can we say to the blank yellow-white fields? What should we inscribe along the straight lines of trees?