The Letters of T. S. Eliot, Volume 1: 1898-1922 (16 page)

Read The Letters of T. S. Eliot, Volume 1: 1898-1922 Online

Authors: T. S. Eliot

1–TSE put ‘Monday 8 September’.

2–See ‘London, The City of Refuge’: ‘This invasion has turned London into a city where alien tongues can be heard everywhere. In omnibuses and trains, in the shops and theatres, one sees foreigners and one listens to foreign speech. One might almost suggest that London’s motto should be, “Ici on parle Français”, for in certain parts of the city the language of our allies is heard almost as frequently as our own. The bulk of London’s French and Belgian guests are women and children, whose men are under arms …’ (

The Times

, 10 Sept. 1914, 4).

3–See ‘Severe German Defeat’,

The Times

, 8 Sept. 1914, 8: ‘In an attack on the southern section of the Antwerp fortifications yesterday the Germans lost a thousand dead and retreated towards Vilevorde in a demoralized condition.’

4–‘The Rosary’ (

c

.1901): poem by Robert C. Rogers, music by Jennie P. Black.

5–‘I am aware of the damp souls of housemaids / Sprouting despondently at area gates’ (‘Morning at the Window’, 3–4).

Eleanor Hinkley

MS

Houghton

8 September [1914]

28 Bedford Place, Russell Square

My dear Eleanor

Here I am in Shady Bloomsbury, the noisiest place in the world, a neighbourhood at present given over to artists, musicians, hackwriters, Americans, Russians, French, Belgians, Italians, Spaniards, and Japanese; formerly Germans also – these have now retired, including our waiter, a small inefficient person, but, as one lady observed, ‘What’s to prevent him putting arsenic in our tea?’ A delightfully seedy part of town, with some interesting people in it, besides

the Jones twins, who were next door for a few days, and Ann Van Ness

1

who is a few blocks away. I was quite glad to find her, she is very pleasant company, andnot at all uninterestingquite interesting (that’s better). Only I wish she wouldn’t look like German allegorical paintings – e.g. POMONA blessing the DUKE of MECKLENBURGSTRELITZ, or something of that sort – because she hasn’t really a German mind at all, but quite American. I was in to tea yesterday, and we went to walk afterwards, to the Regent’s Park Zoo. The only other friend I have here now is my French friend of the steamer, just returned from Paris, who is also very interesting, in a different way – one of those people you sometimes meet who do not have much discursive conversation on a variety of topics, but occasionally surprise you by a remark of unusual penetration. But perhaps I do her an injustice, as she does talk pretty well – but it is more the latter that I notice. Anyway it is pleasant to be in contact with a French mind in a foreign city like this. I like London very well now – it has grown on me, and I grew quite homesick for it in Germany; and I have met several very agreeable Englishmen. Still I feel that I don’t understand the English very well. I think that Keith

2

is really very English – and thoroughly so – and I always found him very baffling, though I like him very much. It seemed to me that I got to know him quite easily, and never got very much farther; and I am interested to see (this year) whether I shall find it so with all English; and whether the difficulty is simply that I consider him a bit conventional. I don’t know just what conventionality is; it doesn’t involve snobbishness, because I am a thorough snob myself; but I should have thought of it as perhaps the one quality which all my friends lacked. And I’m sure that if I did know what it was, among men, I should have to find out all over again with regard to women.

Perhaps when I learn how to take Englishmen, this brick wall will cease to trouble me. But it’s ever so much easier to know what a Frenchman or an American is thinking about, than an Englishman. Perhaps partly that a Frenchman is so analytical and selfconscious that he dislikes to have anything going on inside him that he can’t put into words, while an Englishman is content simply to live. And that’s one of the qualities one counts as a virtue; the ease and lack of effort with which they take so much of life – that’s the way they have been fighting in France – I should like to

be able to acquire something of that spirit. But on the other hand the French way has an intellectual honesty about it that the English very seldom attain to. So there you are.

I haven’t said anything about the war yet. Of course (though no one believes me) I have no experiences of my own of much interest – nothing, that is, in the way of anecdotes, that are easy to tell – though the whole experience has been something which has left a very deep impression on me; having seen, I mean, how the people in the two countries have taken the affair, and the great moral earnestness on both sides. It has made it impossible for me totakeadopt a wholly partizan attitude, or even to rejoice or despair wholeheartedly, though I should certainly want to fight against the Germans if at all. I cannot but wonder whether it all seems as awful at your distance as it does here. I doubt it. No war ever seemed so real to me as this: of course I have been to some of the towns about which they have been fighting; and I know that men I have known, including one of my best friends, must be fighting each other. So it’s hard for me to write interestingly about the war.

I hope to hear that you have had a quiet summer, at best. Did Walter Cook ever call? If you have seen Harry [Child] let me know how he is, and that he is not starving himself.

Always affectionately

Tom

PS (After rereading). Please don’t quote

Pomona

. It’s perhaps a literary as well as a social mistake to write as one would talk. I apologise for the quality of this letter anyway.

1–Ann Van Ness (b. 1891), daughter of a Unitarian Minister.

2–Elmer D. Keith (1888–1965) graduated in 1910 from Yale, where he won the University poetry prize. A Rhodes Scholar at Oriel College, Oxford, 1910–13, he later worked at Harvard University Press.

Conrad Aiken

MS

Huntington

30 September [1914]

Merton College, Oxford

Dear Conrad,

No, I’m still in London, but I go to the above address Tuesday. I reflect upon the fact that I neglected to add my address to my last. I wait till Tuesday because there is a possibility of dining at a Chinese restaurant Monday with Yeats,

1

– and the Pounds. Pound has been

on n’est pas plus

aimable

,

2

and is going to print ‘Prufrock’ in Poetry and pay me for it.

3

He wants me to bring out a Vol. after the War. The devil of it is that I have done nothing good since J. A[lfred] P[rufrock] and writhe in impotence. The stuff I sent you is not good, is very forced in execution, though the idea was right, I think. Sometimes I think – if I could only get back to Paris. But I know I never will, for long. I must learn to talk English. Anyway, I’m in the worry way now. Too many minor considerations.

4

Does anything kill as petty worries do? And in America we worry all the time. That, in fact, is I think the great use of suffering, if it’s

tragic

suffering – it takes you away from yourself – and petty suffering does exactly the reverse, and kills your inspiration. I think now that all my good stuff was done before I had begun to worry – three years ago. I sometimes think it would be better to be just a clerk in a post office with nothing to worry about – but the consciousness of having made a failure of one’s life. Or a millionaire, ditto. The thing is to be able to look at one’s life as if it were somebody’s else – (I much prefer to say somebody else’s). That is difficult in England, almost impossible in America. – But it may be all right in the long run, (if I can get over it), perhaps

tant mieux

[so much the better]. Anyway, I have been living a pleasant and useless life of late, and talking (bad) French too. I have dined several times with Armstrong

5

who is very good company. By the way, Pound is rather intelligent as a talker: his verse is well-meaning but touchingly incompetent; but his remarks are sometimes good. O conversation the staff of life shall I get any at Oxford? Everything

à pis

aller. Où se réfugier

? [Everything’s a stand-in. Where can one hide?] Anyway it’s interesting to cut yourself to pieces once in a while, and wait to see if the fragments will sprout.

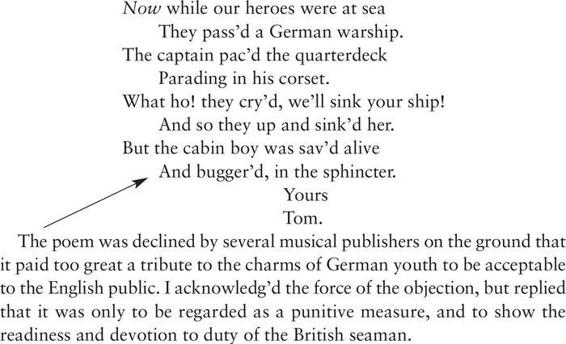

My war poem, for the $100 prize, entitled

UP BOYS AND AT’EM!

Adapted to the tune of ‘C. Columbo lived in Spain’ and within the

compass of the average male or female voice:

I should find it very stimulating to have several women fall in love with me – several, because that makes the practical side less evident. And I should be very sorry for them, too. Do you think it possible, if I brought out the ‘Inventions of the March Hare’,

6

and gave a few lectures, at 5 p.m. with wax candles,

7

that I could become a sentimental Tommy.

8

1–William Butler Yeats (1865–1939): Irish poet and playwright.

2–‘Pound couldn’t have been kinder’: TSE called on Ezra and Dorothy Pound (for EP, see Glossary of Names) at 5 Holland Place Chambers, Kensington, with an introduction from Aiken, on 22 Sept.

3–On this same day (30 Sept.), EP wrote to Harriet Monroe, editor of

Poetry

, telling her that ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ was ‘the best poem I have yet had or seen from an American. PRAY GOD IT BE NOT A SINGLE AND UNIQUE SUCCESS. He has taken it back to get it ready for the press and you shall have it in a few days.’ EP sent the poem in Oct., writing ‘Hope you’ll get it

in

soon.’ When Monroe demurred, he wrote: ‘No, most emphatically I will not ask Eliot to write down to any audience whatsoever … Neither will I send you Eliot’s address in order that he may be insulted’ (9 Nov.). To further objections, he replied: ‘“Mr. Prufrock” does not “go off at the end”. It is a portrait of failure, or of a character which fails, and it would be false art to make it end on a note of triumph. I disliked the paragraph about Hamlet, but it is an early and cherished bit and T. E. won’t give it up, and as it is the only portion of the poem that most readers will like at first reading, I don’t see that it will do much harm’ (31 Jan. 1915). Finally he implored her (10 Apr.), ‘

Do

get on with that Eliot’ (

Selected Letters of Ezra Pound

1907–1941,

ed. D. D. Paige, 1950). The poem was published in

Poetry

6: 3 (June 1915).

4–‘Oh, these minor considerations! …’ (‘First Caprice in North Cambridge’, l. 11 (

IMH

).

5–Martin Armstrong (1882–1974), British author, was serving as a private in the 2nd Battalion, Artists’ Rifles.

6–This is the title, cancelled by TSE himself, on the flyleaf of the Berg Notebook (

IMH

, i).

7–A whimsical thrust at gatherings in Harold Monro’s Poetry Bookshop.

8–Playing on his own name and J. M. Barrie’s title,

Sentimental

Tommy

(1896).

The Chairman of the Committee on Sheldon Fellowships

MS

Harvard

2 October 1914

Merton College, Oxford

Dear Professor Briggs,

1

In accordance with the requirements I send my address, which willremain the same throughout the year. I had expected to go to Germany

for the spring term, but this will now evidently be impossible, so I shall remain here until the end of the year.

Very sincerely yours

Thomas S. Eliot