The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (47 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

In about three months, Stashek Gleiksman sailed from Bremerhaven to New York, got an Ellis Island name change to Sidney Glucksman, and moved into the Klein family’s apartment in Crown Heights. Jerry was thrilled. “I never had any brothers or sisters, so for that period, it was like having a younger brother around.”

After about six months, Sidney moved to New Haven, where a community of concentration camp survivors had gathered. Jerry went back to City College, got a degree in business administration, and ultimately became a commercial photographer, owning a photo agency that represented other photographers. He married, but it lasted only seven years, and they never had children.

Sidney had met a girl in a displaced persons camp in Munich. She eventually came to the United States, and they were married. He put his skills as a master tailor to work and fifty years later still operates a well-regarded custom tailoring shop in New Haven. He and his wife have two daughters and several grandchildren, and Jerry Klein, one of the soldiers who freed him at Dachau, is, for all practical purposes, a member of the Glucksman family.

And is the Nazi era behind them? Not quite. Before Dachau, Klein had been a religious Jew. Every morning, whether in the trenches or in a half-track, he’d put on his tallis, the Jewish prayer shawl, and tefillin, and prayed. “All the fellows in the half-track kept quiet while I said my prayers. I’m sure they were convinced that God was protecting them along with me. And then, when I saw Dachau, I just lost faith. I have been a nonbeliever ever since.”

His loss of faith happened very quickly. “I realized that there could be no essence of any kind that, having the ability to control human behavior, would allow such a thing to happen, so I had to believe that there was no such an essence.”

It’s a conclusion that requires the free-will counterargument, that God gave mankind free will and therefore God can’t interfere with whatever man does. “Then God did a lousy job,” responds Klein without hesitation, “and I can’t believe that this almighty creature would have, if it existed, done such a lousy job.”

Sidney Glucksman, on the other hand, is a believer. Even more, he believes God has given him a mission to make certain that people don’t forget the Holocaust. “I’m still working. I have my own shop, but when they call me [to speak], I say, ‘Anytime.’ I drop everything, and I make a date, and I go. Because I always say that I’m alive because God wanted me to be alive so I should be able to tell the story about it.”

One of those calls got him involved with the production in New Haven of

The Gray Zone

, a dramatic play by Tim Blake Nelson that takes place in Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944. Sidney became, in essence, a technical adviser. At the conclusion of one performance in front of an audience of hundreds of people, a woman stood up to ask him a question. “She says, do I feel guilty to be alive? So you know what my answer was? I asked, ‘What nationality are you?’ She told me, ‘German.’ So I said to her, ‘Well, God wanted me to be alive so I should be able to tell the true story of what happened, what you people did to us. That’s why I am alive. And that’s why I’m doing what I’m doing. And now you can go to hell,’ and I walked out.” To hearty applause, he added.

Morton Brooks, né Brimberg

Boynton Beach, Florida

BERGA

The soldiers who liberated the concentration camps came home to the United States intent on getting on with their lives. They had the GI Bill, and most of them had the thanks of a grateful nation. There were exceptions …

Morton Brimberg, who managed to survive as a prisoner of war in the slave labor camp at Berga, was physically rehabilitated, discharged from the Army at the end of 1945, and enrolled in college at Buffalo a month later. He completed his undergraduate program in a little over two years. Then Brimberg the veteran, Brimberg the ex-POW, Brimberg the Jew ran smack into the lack of that gratitude of a grateful nation everyone hears about during those Veterans Day speeches.

“I wrote letters asking for applications to graduate schools, and I wasn’t getting a response just asking for the application, and someone said to me, ‘Maybe it’s because of your name.’ I had written letters [signed Brimberg, and then] I sent out postcards to the same schools under Brent, Brandt, and Brooks, and I got immediate responses to the postcards. So I said to my wife, ‘Maybe it is the name, and how do you feel about changing it?’ She says, ‘Fine,’ so I put in for a name change.”

So Morton Brimberg, who was sent to die in a Nazi slave-labor camp because he was a Jew, came home and had to deny his Jewishness. He was accepted to graduate school and became a PhD clinical psychologist and assistant director of a department at the University of Buffalo Medical School, where he was responsible for integrating the behavioral sciences with the medical. The discipline that had helped him survive Berga helped him survive overt discrimination in postwar America. “I learned about camouflage, and I felt, if this is helpful, the hell with it. It’s dealing with the situation, just doing something to cope and deal with the situation.”

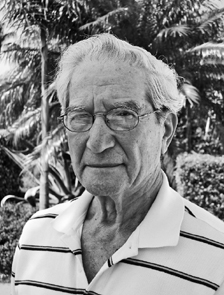

U.S. Army veteran and Berga survivor Morton Brooks, PhD

.

Brooks dealt with dreams and nightmares from the beginning and, when interviewed for this book, said he still has post-traumatic stress disorder and still goes to an ex-POW group at a VA hospital. He’s been able to deal with the hate, to deal with the dreams of pinning the Berga commandant up against a wall and carving him up with a knife. But he had difficulty with the final years of the Bush presidency. “It scares me with Bush that in terms of how close his behavior has been to Hitler in terms of legally making rules and regulations in violation of constitutional law. And that the Congress didn’t stand up more to him with some of the things that he’s done. When they pass a law that says he shall go to court and prove the need to examine someone’s communications and just disregard it, to me this is Hitler behavior, and it’s scary.”

Norman Fellman

Bedminster, New Jersey

BERGA

Unlike Mort Brooks, Norman Fellman kept his Berga experiences bottled up, in part because before the Army would discharge him, it made him sign an official, classified document agreeing that he wouldn’t disclose anything that had happened to him while he was a prisoner of war. The ostensible purpose of the document was to keep other enemy countries from knowing what activities American POWs might have undertaken that were inimical to their captors.

Nevertheless, Fellman told his parents what he’d been through, and he did tell Ruth, his future wife, about his experiences. “When I realized that we were serious and I wanted to ask her to marry me, I thought she had a right to know that she was getting damaged goods. And so we talked for hours, and I answered her questions.” But for the first fifty years after the war, he says, “nobody even knew I was in the service. I never spoke of it.”

He didn’t tell his older daughter until she was eighteen or nineteen. His younger twin daughters didn’t know about Berga until they were grown up and married. The first time they heard the story was when he gave a talk at their temple.

Keeping the secret had consequences. “I knew I was sitting on a ton of anger and I was repressing it, and when I was younger, I was able to repress it pretty good, but it has been spilling out. It still spills out. It’s the chief reason that we have marital differences that we have now, and we’re married fifty-eight years. And they tell me at the VA that it’s PTSD spilling out, so the anger has been coming out in bits and pieces.” Except that he didn’t begin going to the

VA

POW rap sessions until 1986.

The sessions were a start at changing his life. “The first time I walked into that room, it was like somebody took a ton off my shoulders, and I had never realized. Not having to guard myself, not having people disbelieve. I’ve had doctors who don’t believe some of the things that happened—and said so.”

One of them was a

VA

doctor, who some years back said to Fellman that he was making it all up, that it had never happened. “I would’ve gone over the counter for him, but luckily, I didn’t. No, it’s been a long road. [And I’m] still walking it. I find that each time I tell the story, there’s a little less anger.”

U.S. Army veteran and Berga survivor Norman Fellman and his wife, Ruth, outside their home in Bedminster, New Jersey

.

He’s able to talk about his experiences now, and he can calmly put them into context and perspective. “We were just one little element. We had 350 military. The rest in Berga were all civilians, and there was torture going on and everything else. Everything else that went on in a concentration camp was happening there. It was a work camp, but they worked you to death, and I’m serious. The purpose of a POW camp, and they had slave labor in those POW camps, but the idea was to feed you enough to get the most amount of work out of you for the least amount of food and keep you alive. In a concentration camp, the idea was to work you until you couldn’t work anymore, and when you couldn’t work anymore, they killed you or you died on the job. The end result was your demise.”

He didn’t grasp the magnitude of the Holocaust until long after the war. “I don’t think I did while I was there, because it was a microcosm that I was in; it was all I knew. But when you begin to see the number of camps—Dachau and on and on and on, only then could you begin to get the magnitude. We were a pimple; we were a blister. What happened in our camp was a very tiny part of what was going on, but whatever happened in any camp happened there.”

And then there’s the matter of survival. “Your mind has a lot to do with whether you manage to live or not. You can endure more than you can conceive of if you refuse to believe that it’s going to kill you. If you don’t give up.”

Ultimately, there’s the question about God. “Do you still believe?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Why not? I’m here, you know.”

“It’s the quintessential Jewish response.”

“Exactly.

Voo den?

[What else?]

”

Bernhard “Ben” Storch

Nyack, New York

SACHSENHAUSEN, SOBIBOR, MAJDANEK, and CHELMNO

It didn’t take long for Ben Storch and his new bride, Ruth, to realize that not only was there no life to rebuild after the war in their native Poland, the odds were high that as returning Jews, they’d both be killed by anti-Semitic Poles who didn’t want the Jews coming back and reclaiming their property. So they set off on an odyssey that took them through several displaced persons camps before arriving in Munich, where they registered to immigrate to either the United States or Palestine.

In March 1947, they were notified that they’d been granted a visa to go to the United States. They sailed for New York from Bremen on April 10 and arrived on April 22. They were met by his uncle, who lived in Brooklyn. Ben Storch spoke no English, but he was a master tailor and was able to get a job working in a factory in Long Island City. At the end of 1952, he became an American citizen.

“I did not speak about the Holocaust stories for twenty-eight years,” he says. “My head was not healthy. I had headaches, dreams. I’d smoke overnight.” He saw a psychiatrist and “got healed, mentally. Everything cooled down. Then children came, and I stopped smoking. Mentally, the children brought me back to life, really. When I came back after the war, I never hated. Don’t ask me how, I did. I just want to have peace.” His equanimity is all the more remarkable when one considers that his mother died in the extermination camp at Belzec, Poland, along with 400,000 other Jews, and his three brothers were murdered in Auschwitz. But he bears no malice toward the German people. He says, “I want to have those kids, when they grow up in Germany, they should have peace. [But] they should be told everything.”