The Lightning Keeper (6 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

Amos Bigelow sat in the back, well pleased by the air from the open window and by the contemplation of this quantity of water, even though it was, strictly speaking, useless to him being so many miles from his waterwheel, not to mention hundreds of feet downhill.

He had talked himself out yesterday, first to Stephenson, then in the car, and at dinner too, when he had questioned Harriet closely about this young man. Today he had only one question to put to Toma, which was whether he understood the principle of the waterwheel. When he had received this assurance he fell back into a comfortable silence, punctuated every now and again by a muttered phrase like a line from a play, for the sight of the two young people there in the front, both of them looking straight ahead and never at one another, put him in mind of his own courtship, of which that trip to Italy had been a last sad reprise, and he was in fact now conversing with his wife, whose answers he heard with such blessed clarity.

When they heard snoring from the back, the young people might have relaxed their poses of rigid vigilance, might have commented on the weatherânow hot, now cold, would it be winter or summer tomorrow?âmight have found some other topic of conversation, perhaps suggested by the city, now vanished, or by some geographical feature of the rich, wet valleys of southern Connecticut unfurling before them. Those possibilities of comparison and contrastâthe city and the country, his home and hersâwere present to Harriet's mind, and she further imagined how a slight rearrangementâa yawn combined with a perfectly natural stretchingâwould allow her to view Toma's profile and whatever scenery presented itself on his side of the Packard. And when some precipice above the river or some stately mansion came into view she would describe it to him, with the slight emphasis of her hand on his, for he really could not take his eyes from the road for more than a second.

She imagined these possibilities because she remembered so well the ease of conversation they had known in Naples, and could recall, if she allowed herself to do so, the exact sensation produced by his skin touching hers. It had happened in Naples, of course, and last night in the car, and even this morning when she was so clumsy with the napkin and he caught both the falling bread and her hand in his. She wondered if such things leave a mark, a phosphorescence visible only to her. When the ship had left Naples, in the evening, she had escaped from her cabin and spent half the night watching the endless wake

whose faint glow, could she but follow it, would always lead her back to Toma.

She had told him the truth this morning when she said how near she had come to visiting him in the car. She had imagined it all at once, an instant whose intensity brought blood to her face: he would be cold and hungry and aloneâ¦it was like a scene on the stage. Her part was to bring him food and warming drink. Her dramatic imagination stopped short with her showing him, by the light of a candle end, that the back of the driver's seat opened just so, and there inside was the fur-trimmed lap robe.

The porter had shown them to their rooms and had humiliated her with a murmured question: No luggage then, miss? Her father, flushed with his two glasses of wine, had kissed her on the forehead and said, either to her or to the porter, Well, I guess we'll make do for the one night. He had tipped the man too generously, and when the porter put his hand to the gilt-trimmed door joining the two chambers, had said, No, no, we'll leave that be.

She removed her dress, shook it vigorously, and hung it on the door of the armoire, hoping that all traces of the journey might vanish overnight. Her face, in the mirror of the washstand, and in the harsh electric light overhead, seemed different to her, tired and perhaps older. She washed as best she could, but even soap could not erase the memory of the dormitory where her thoughts now carried her. She looked at her shoulders, at the line of her neck, and tried to remember Toma in the baths at Herculaneum, his breath in her hair. Did he still smell like that?

The room, soundless and unfamiliar, encouraged a bleak train of thought. Did not men meet women in such places, women unaccompanied by luggage? If she had thought to visit him in the car, might he have thought recklessly of coming to her here?

Harriet switched off the light, then found her way to the bed, where the linens chilled her to the bone. She said her prayers feeling very far from God and slept at last, but not without dreaming, and those dreams, and her waking thoughts, and, most of all, the ruined arc of her imagined connection to this man beside her now made her mute.

As they made their way north from New York and the hotel, the fa

miliar landmarks of the journey tempered her despair, and she began to feel more like herself. In spite of the bright sun it was colder now as they began to climb, and the road grew less certain, alternating between open water and piles of slush sculpted by the last wheel or hoof to pass this way. They came to the foot of Great Mountain, and Toma, in response to the pressure of her hand, slowed the Packard to look up at its icebound heights, where stunted oaks bowed under their burden.

“It often happens thus,” she said, breaking the hour of silence since they had stopped to refill the gas tank. “They call Beecher's Bridge the Icebox of Connecticut, and when the towns around us have rain we are likely to have snow, especially in the spring. But this is unusual, even for us. Look at the little birches bent right to the ground. If it does not thaw by tomorrow they may never stand upright again. Papa will be upset when he sees this: he will be worried about the ice on his wheel, about having to shut down the works.”

Toma did not respond other than to nod his head, but he glanced from the road to the outcrops of ragged, glistening rock, and to those refractions of light from every limb and twig that bathed the car in a nimbus.

“This is truly a land of wonders,” he said at last.

Now the road was frozen solid, and strewn with a windfall of ice shards from the tall elms. The wheels lost their purchase, and Toma slowed almost to a walking pace, keeping the left wheels on the rutted crown. When they came to a slight incline he let the Packard roll to a halt without touching the brake.

“Are we there already?” boomed Amos Bigelow, suddenly and cheerfully awake. “Well, what's this? Ice, for all love, ice. You should have woken me sooner. Shall I give us a push?”

“No, Papa, we'll wait. It's more than two miles to town, and it's uphill, as you know.”

“Someone may come along, as you say, but he'd better be quick about it or I'll have to take shank's mare. Horatio will have stopped the wheel, in spite of what Mr. Brown says. Another day lost for sure.”

Someone did come along: Walter Hubbard with his oxcart and just a light load of hay on it. Bigelow offered him a dollar to pull the Packard the rest of the way.

“It's no trouble to me, Mr. Bigelow. I'm going anyway, and the boys won't mind the weight. It's a slow way, but a sure one.”

Slow it was, and although Bigelow's impatience was palpable, Toma seemed to be in an unaccountably good mood.

“What pleases you so, Toma? Why do you smile like that?”

“It is the beasts, only that. I am six years in your country and I have never seen an ox until now. I am thinking of my home.”

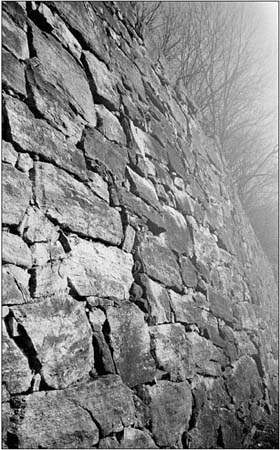

The wall of the Power City canal

No account of the so-called North West Corner, and certainly of Beecher's Bridge in particular, can stray far from that distinctive topography that has been our blessing and challenge ever since those hardy colonists, our forefathers, first pushed into “the Greenwoods,” to bring honest industry into what had been the haunt of wild animals and aboriginal Indians. Time, patience, and a great deal of earnest labor have been necessary to channel the Bounty of Nature toward the Progress of Mankind in these parts. These steep and unforgiving hills, which for so long impeded the ebb and flow of commerce, were also, from earliest times, the source of mineral treasures not yet fully exploited, and have at last yielded themselves to the harness of the rails. The forest is now the preserve of the charcoal maker, whose exertions provide the fuel for our principal industry, iron making. The narrow river bottoms have provided for the farmer's needs if not his luxury, and many a watercourse has been dammed to power the mills and workshops where mechanicians put flesh on the dreams of inventors, so that the very name “Connecticut” is now a resonant synonym for ingenuity and progress.

But the principal feature of this landscape, to the inquiring eye of an historian such as myself and in the sober calculations of the entrepreneur, is the dramatic and dominating bulk of Great Mountain itself. Let us imagine ourselves borne aloft in the gondola of a swelling balloonâwe are not so rash nor so ignorant of mythology as to aspire

to such a vantage by means of the Wrights' ingenious creationâwhere we may view without hindrance or apprehension this noble landmark that has attracted so much admiration and indeed shaped the aspirations and fortunes of those townsmen, farmers, and mechanicians who live in its shadow.

It is a day in early spring, and the shelving rock of the broad plateauâfor here is no Andean cone, no Pyrenean toothâis softened by a gauze of faintest green, the crescent bud and leaf of the forest, dotted now and again by the glory of our shadbush, which so resembles a puff of smoke and is as soon vanished. The season is not so far advanced that maple, oak, and cherry will obscure the contours of the land, though a deeper, unfailing green marks those descents where hemlocks guard the mystery of their watercourses.

The severity of the original forest is tempered, for we see that certain stands of hardwood have been felled by the raggies for charcoal, and the more accessible hemlocks by the tanner for their bark. Those stumps, some ancient and of heroic girth, gaze up at us through the branches of more recent growth. There are pasturelands as well, though the season is too early for the farmer to trust his livestock to the conditions that prevail here. And there, practically at the western extremity of the mountain, not far from the crenellated walls that loom above the town of Beecher's Bridge, another mystery of Great Mountain is revealed to our aerial gaze: a lake ringed with acres of impenetrable alder like any mud pond on lower ground, but its color is the most brilliant sapphire blue, denoting a depth that, to our knowledge, has yet to be plumbed. For the lake has its legends, and we will not attempt here to credit or disprove them; but in the history of Beecher's Bridge it has had only one name: Dead Man's Lake.

The breeze has carried us west over the lake, over the brow of the mountain, and below us now we see the town laid out in miniature, as if for the delight of children. The disadvantage of our height is that all is flattened out to the dimensions of length and breadth, as on any map, and those works of man that have so engaged the energies and passions of generations are mere toys, and less than toys when compared to the mountain and the river.

To look on the gleaming strands of the railway track you would think that it has just been taken from its box on Christmas Day and

laid down with no more trouble than croquet hoops on a lawn. You would never imagine that just beyond those benign hills to the north lies a wild tumble of rock, a gorge by the name of the Stony Lonesome, and that the construction there claimed the lives of nine men, or ten if we include the engineer of the first train to cross the trestle, who died of a heart attack.

Rails and river converge a half mile from the town where the Long Bridge, parallel to the older, eponymous structure of Beecher's Bridgeâan architectural marvel in its dayâconveys goods and passengers to our eastern bank of the Buttermilk. As the town was laid out before the railroad came here, and as there is not such a distance between the river and the foot of the mountain, the townsmen, both the rich and the poor, have had to make their peace with this energetic and sometimes inconvenient neighbor. And not only the townsmen, but their wives, who must wash their curtains twice weekly to banish the soot, and whose gossip must yield each day to the clamorous interruption of four passenger and six freight trains.

Once past the town, the river begins to drop and to gather speed on its way due south. It is checked briefly by the old upper dam that has diverted some water to the Bigelow Iron Company for well over a century, and again only a few rods downstream by that more ambitious concrete barrier erected by a Bigelow scion, Aaron Bigelow of Civil War fame, father to the present ironmaster. And then the water frees itself from the hand of man to plunge recklessly a hundred and sixty feet in those thunderous cataracts of the Great Falls of the Buttermilk, whose din and mists rise even to the height of our balloon.

Now rails and river diverge, for such an acrobatic display would be fatal to any machinery, and many miles of gentle gradient intervene before they are reunited at Perrysville, near the junction of the Buttermilk and the broad Housatonic. In the triangle of land between these two paths we may glimpse the traces of an even grander ambition belonging to that same Aaron Bigelow.

From the eastern edge of his new damâwhich, unlike the older one, harnessed the entire flow of the Buttermilkâthe ironmaster projected a canal, an earthwork faced in massive stone that descends in a slow serpentine, the better part of a mile from bend to bend, until it rejoins the river below the falls. Along the canal, at irregular intervals

on the various tiers, stand foundation works and sometimes entire buildings now fallen to ruin, and this is all that remains of the dream of Aaron Bigelow, the dream he called Power City.

On the ground there is not much to see, and few to see it anyway, for there are superstitions attached to this place that distilled so much pride and ill luck and animosity. The history of Beecher's Bridge, according to the Congregational minister who preached here for almost fifty years, is by and large the history of failed enterprise; and if that be true, then here in these damp thickets entwined with the great weed-choked serpent of the canal, here is failure writ in stone, and the intrepid local historian, or perhaps the errant tourist, considers one of these canal walls, twenty feet high and vanishing right and left into the forest, with the same awe and pity as one who encounters the remains of Nebuchadnezzar's palace or the fallen statue of Ozymandias.

It was not a bad or a foolish plan, this Power City, or, if it was, then at least many people shared it, and sought to tie their own fortunes to Bigelow's vaulting ambition. He was, physically, a big man and had already achieved a great fortune by dint of his daring. In 1860, Aaron Bigelow, having recently taken control of the ironworks from his own father, set about tinkering with a new process whereby iron was cast into rings and the rings then fused together to make a tube of superior properties. Bigelow thought he was improving the performance and durability of the cast pipe of those days, and he imagined burgeoning new markets in the metropolises of Hartford and Springfield, even Boston and New York: aqueducts or sewers, depending on which way the water was running.

Then history intervened in the form of the Civil War, and Aaron Bigelow's cast ring pipe was reincarnated as a cannon barrel that could withstand greater pressure, and hence achieve greater range, than conventional cannon of equivalent weight. Patents were taken, and this efficient engine of destruction, the Bigelow Rifle as it was called, made a great fortune for its inventor, and gave him pride of place among the capitalists and industrialists of the North West Corner.

The war came to an end, and life returned to its old ways in Beecher's Bridge and at the Bigelow works. Some of the men had to be laid off, of course, for although the Bible speaks of beating swords into ploughshares, in practice the Bigelow Rifle would not be changed back

into pipe. The orders never materialized: the ring-casting process was deliberate and costly, and the product was of an awkward bulk and heft for a manufactory serviced by no railroad or canal link. During the war, each cannon barrel was ferried or floated across the Buttermilk, then carted eight miles to the nearest railroad depot. Aaron Bigelow understood that he had been defeated as much by the difficulty of transportation as by the unwillingness of municipal officials to invest in plumbing of the highest grade.

Bigelow was still a young man, not yet forty, and he was very, very rich. But he did not think that it was time to rest on those laurels; he must do something, else Beecher's Bridge would be forever cut off from the outside world, or at least handicapped in its pursuit of progress. He still came to the works every day, and on his way past the cannon would rub the decorative brass B for good luck. This cannon, a Bigelow eighteen-pounder, squatted in the dust at the entry to the ironmaster's office, chained off from the general chaos and drayage of the works by huge iron links cast by Bigelow's great-grandfather and salvaged from the chain that had once prevented British warships from navigating the Hudson. The cannon was the first fruit of Bigelow's process and patent, and in order to encourage visiting generals and politicians, Aaron Bigelow would sit astride the charged cannon and light the fuse with his own cigar. When the smoke cleared, there was the ironmaster, grinning and puffing his cheroot as if nothing had happened, and his audience, mouths agape and ears still ringing, would applaud. Young Amos Bigelow, much taken with the spectacle, asked each time if he might join his father in this adventure, and was told by Aaron that this was a man's business, and no game.

The cannon and the chain were potent reminders of what Bigelows could do when they turned their minds to something, and they gave Aaron Bigelow no peace: surely some greater work awaited him than merely filling orders for iron wheels. The story, perhaps true, is that the idea for the canal that would harness the Great Falls came to him in the middle of the night, and that he rose from his bed and began the labor himself with a pick and shovel, young Amos holding the lantern. When the sun rose he stalked into the woods in his nightshirt with an axe and several yards of bright ribbon from Mrs. Bigelow's sewing basket to map the course of his dream. Saplings were

cut and trimmed, then hammered into the ground with the flat of the axe, a scrap of ribbon as the final touch. Three great loops were laid outâsome say the plan was determined by the amount of ribbon in his pocketâto return the water taken above the falls to the river below, and Bigelow calculated that there was room enough for eighty-five mills, each receiving water from its section of the canal and spilling it back into the level below.

Eighty-five mills representing any and every conceivable enterprise requiring power: weaving, wood turning, tool manufacture, gunsmiths, box makers, tanneries, breweries, silk spinningâ¦on and on went the list. Nothing seemed impossible to Aaron Bigelow, and, as he was fond of pointing out, after the canal was built, it was all free, for so long as the Buttermilk River should flow. Yes, the canal would be expensive, as every great work from the pyramids on must have been, but Bigelow was able to paint such a picture of Power City with all those wheels turning day and night that he found many willing investors, some of whom built their factories while the canal was being dug.

To the town fathers, and to the men of substance throughout the North West Corner, the plan, and its larger ramifications, had a compelling, dizzying logic. Even before the capital had been raised, the railroad commission made a recommendation to the legislature that the main line of the railroad be rerouted through Beecher's Bridge. And this was not all: a bank note printed in 1875 by the Iron Bank of Beecher's Bridge shows a foreshortened perspective of the town and the ironworks against a background of tall masts and swelling canvas. Not only would the railway come to the magnet of Power City, but a series of locks and canals on the Housatonic and the Buttermilk would bring oceangoing cargo vessels to the new metropolis at the foot of Great Mountain.

Aaron Bigelow was an iron maker, not an engineer, and therein lay the fatal flaw of his scheme. In order to move the water of the Buttermilk past the hundred waterwheels of Power City, he needed a dam and a canal. Bigelows had built dams before: the old dam on the Buttermilk itself that diverted water through the ironworks, and several smaller dams along tributary streams to create holding ponds or reservoirs against those droughts that could shut down the works for weeks in the dog days of summer. This new dam did not daunt him, though it

must be built to span the entire watercourse and would divert much, and sometimes all, of its flow. The dam was built, and it stands to this day: see how the water, still pale and turbid from snowmelt, falls like a veil over its top.

Perhaps he gave less consideration to the construction of the canal after he had laid it out; perhaps he was distracted by the great work of promoting his idea and raising the capital for it; perhaps he thought that a canal is no more than a ditch: you dug it out, and it worked. Except that this canal, because of the slope of the land, was more aqueduct than ditch, as those impressive stones in the undergrowth below us will attest. The work seemed to be done carefully enough. Every two hundred feet or so there is a section of the wall where the stones do not lap each other, and straight vertical cracks, six feet apart, run down from the parapet. These are the blanks, so-called, where the stones could be knocked out without damage to the structure and a wooden flume inserted, thus diverting water to the wheel of that particular enterprise. So proud of their work were the masons that now and again they signed it, leaving initials and dates, sometimes an inscription in Latin, like so many tombstones set in the wall.