The Lions of Little Rock (10 page)

Read The Lions of Little Rock Online

Authors: Kristin Levine

19

COLORED

Friday afternoon finally came. I wasn't sure what I should do. On the one hand, the federal marshal showing up the night before had spooked me. And Daddy had told me to stay away from Liz. On the other, I really wanted that math book. I'd earned it. There could be no harm in meeting her, getting the book and leaving. At least that's what I told myself. But the truth was I just wanted to see Liz.

I meant for her to meet me by the lions, but she wasn't there when I arrived. After a few minutes, I decided to walk around the zoo to see if she was waiting somewhere else. The monkeys were chattering at each other and ignored me. The flamingos slept on one leg, their heads under their wings. Even Ruth wouldn't take the peanuts I offered.

I was in a foul mood. How dare Liz not show up? She probably wouldn't even bring the magic square book if she did. She'd lied to me. She'd used me. Picked the dumb white girl for a friend, because even if I did find out her secret, I wouldn't tell anyone. Part of me knew that didn't make senseâif she'd wanted me only to stay quiet, why had she worked so hard at getting me to talk?âbut as I walked around the zoo, my disappointment grew, and I nursed my anger like a jawbreaker that grew hotter and hotter as I rolled it around on my tongue.

I went back to the lion's cage. There was a strange girl on the bench, with a bandanna tied around her head and big sunglasses and a patched coat. She was looking off in the other direction. I had just decided to give Liz five more minutes before I left when I noticed there was a book on the bench next to the girl. A big book. A math book.

“Liz?” I ventured.

The girl turned to face me. “You came,” Liz said.

“Of course I came,” I said. “I invited you.”

“You weren't here when I got here.”

“I was,” I insisted. “

You

weren't here, so I went to look around. Visited Ruth and her friends.”

We stared at each other for a minute, not exactly scowling, but not smiling either. Maybe Daddy was rightâmaybe now she was a completely different person after all.

Liz looked down at the ground. “Why don't you just say it,” she said.

“Say what?” I asked.

“Ask me. Isn't that why you wanted to meet me here?”

Questions swirled in my head:

Why did you lie? Why didn't you tell me? Did you like me at all, or was our friendship a story too?

But what I said was the obvious question. “Are you really colored?”

Liz nodded.

I sat down next to her. “You don't look colored.”

“It doesn't matter what you look like,” said Liz. For the first time since I'd known her, Liz dropped her friendly mask. “I am colored. Do you have a problem with that?”

I wasn't sure. If you'd asked me last summer if I wanted a Negro for a friend, I'd have said no thank you. I'm sure they are very nice, but I'll stick to my own kind. Birds of a feather flock together, right? But this wasn't some random hypothetical Negroâthis was Liz. “I'm not sure,” I said finally. “Why did youâ”

“I don't know,” said Liz miserably. “My parents told me to go to West Side Junior High, so I went. Do you ever talk back to your parents?”

I thought about the conversation with my father in the car. Meeting Liz probably qualified as talking back. “Sometimes,” I admitted.

“Well, I don't,” said Liz. “They're my parents. They have their reasons. I have to trust them.”

I waited. There was more she had to say. And

if there's anything a quiet girl knows, it's how to listen.

Sure enough, after a moment Liz began to speak again. “My mother is real smart. She's like you in math, it comes natural to her without even thinking. But she had to quit school when she was fifteen and get a job working as a housekeeper in a rich white lady's house. When she should have been a scientist, designing one of those satellites.”

I gave Liz a surprised look.

“What?” she said. “You think white people are the only ones who dream about going to the moon?”

For the first time I realized, not only were there no women among those scientists on TV, there weren't any Negroes either.

“We moved to Little Rock this past summer. My grandmother's getting old, and she has a nice little house but no one to help her take care of it. So we moved in with her. And when Mama told me to go register myself at West Side Junior High, I did, and I didn't ask any questions.

“I haven't gone anywhere with my family in months, just school and home and the zoo with you. My grandmother and I even said our prayers at home. Then last Sunday, my little brother was getting confirmed at church, and we figured this one time, it would be okay for me to go.” She shrugged. “You know the rest.”

No, I didn't. I mean, I knew about Sally and her mother, but what about Liz and me? What was going to happen to us? “Where are you at school now?” I asked.

“Dunbar Junior High,” said Liz. “The colored school. The official story is that I've been real sick and my grandmother's been teaching me at home. But the truth is, everyone knows.” Liz was crying now, small silent tears that dripped out from behind those ridiculous glasses. “No one will talk to me. If I ask a question, they don't respond. If I sit down at a table at lunch, the others get up and leave. Everyone ignores me as if I weren't even there.”

I handed her my handkerchief, and she wiped her eyes. This wasn't the Liz I'd known at all. The Liz I'd met at school was strong and confident, and this one reminded me a lot of myself.

Liz blew her nose and nudged the math book closer to me. “Here's the book.”

“You don't have toâ”

“In your note you said to bring the book. I thought that meant you did the presentation.”

I nodded. “I did. The whole thing. Your part too.” I couldn't keep the pride out of my voice.

“Good for you, Marlee,” Liz said, but she didn't smile. “You earned it.”

This wasn't how I imagined things. I wanted Liz to be proud and happy. “Won't your mother miss her book?”

Liz shook her head. “She was so excited when I asked to borrow it. I didn't have the heart to tell her it wasn't for me.”

I picked up the book and clutched it to my chest. It was warm from sitting in the sun. The last of my anger melted away, and suddenly I knew, despite everything, that I still wanted to be Liz's friend.

“Meet you here again next Friday?” I asked.

Liz shook her head. “Marlee, I can't meet you here anymore. It's dangerous. If the wrong person found out . . .”

She didn't finish and I thought about what Daddy had said.

You let your youngest walk to school tomorrow, she won't make it.

I guess that was why Liz had on the glasses and the bandanna. Though if she was trying not to be noticed, she probably should have picked something less conspicuous.

“Daddy's already talking about moving again,” Liz went on, “but Mother has a housekeeping job she likes for once, and Grandmother has been here forever, so she won't leave no matter what happens. Besides, Mama's not the type to run. Even if it is dangerous.”

“Are you scared?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Liz. “I am.”

I was too. At least, I tried to be. It was hard to believe that someone would really try to hurt us, when the sun was shining and we were at the zoo, and everything seemed so normal.

“Well,” I said, “you can always take a deep breath.”

Liz snorted. “Imagine them in their underwear.”

“Two, three, five, seven, eleven.”

We both giggled.

Liz leaned over and put her head on my shoulder. “Aw, Marlee, you are a good friend. I'm sorry I can'tâ”

“Please,” I said. “Daddy sent Judy away to live with Granny in Pine Bluff.”

“What?” said Liz, sitting up straight.

“She's going to go to school there,” I explained.

“But who is there left for you to talk to?”

“Exactly,” I said.

Liz was silent for a long time. “I don't have anyone to talk to, either.”

I held my breath.

“Give me the book for a minute.”

I handed the book back to her. Liz pulled a pen out of her coat pocket and began to write on the front leaf of the book. When she was done, she handed it back to me.

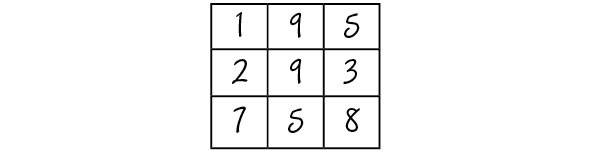

“The first two and the last two digits are the year,” said Liz.

I looked: 1958.

“The other five are my phone number.”

“Five, two, nine, three, seven,” I repeated.

Liz nodded.

“It's not a magic square,” I said. “The rows don't add up.”

“Oh, Marlee.” Liz laughed. “Only you would notice that. Ask for Elizabeth Fullerton when you call. Not Liz. Use my full name. Mother is worried about prank calls and won't let me answer the phone.”

I nodded.

“Don't bother calling until next weekend,” said Liz. “I'm going to be grounded for sneaking out today.”

I nodded again.

“And we need new names. My parents know I have a friend named Marlee at West Side.”

“Mary?” I suggested.

“Nice to meet you, Mary,” said Liz. “When I call you, I'll be Lisa.”

“Lisa,” I repeated.

“I don't know if this is going to work,” Liz admitted.

“Me neither,” I said. “But isn't it worth a try?”

Liz smiled, and for the first time, she looked like herself again. “I have to go. See you, Marlee.” And she ran off.

When she was gone, I opened the math book and looked at the square Liz had drawn. And I decided it was a magic square after all, because it was going to bring my friend and me back together.

20

THE WEC

We went to church as usual Sunday morning at Winfield Methodist Church, but I had a hard time keeping myself from yawning during the sermon. I'd stayed up late the night before reading

Magic Squares and Cubes,

and it was even better than I'd expected. Before, I'd only seen magic squares with three or four rows and columns, but this book had squares with five, six, and even seven. It had a picture of an engraving by Albrecht Dürer that had a magic square in it too. And it even talked about how magic squares were used as talismans to protect you from harm.

I closed my eyes to rest for a moment and thought about the book and Liz and talking. For a long time, I'd thought of myself as only speaking to four people: Judy, David, Daddy and Mother (if she asked me a direct question). Then Liz came along, and things started to change. I answered math questions in Mr. Harding's class most days, and squeezed out a few words to JT. I'd told Miss Taylor I was going to give the presentation, had given it and had a whole conversation with Betty Jean afterward. I'd even spoken to Pastor George. What was going on?

Mother elbowed me in the ribs. I opened my eyes, and she passed me the collection basket. I was supposed to put my one-dollar donation inside, but I was so distracted by magic squares and talking and presentations, I forgot and just passed the basket onto the next person. Drat. At least Mother hadn't noticed. I'd put in two dollars next week to make up for it.

After the service came Sunday school. My teacher, Miss Winthrop, was young, a college girl, I think. She'd only been at our church for a year or two and was sort of annoying and amusing at the same time. She was a little on the plump side and had dimples when she smiled, which was pretty much all the time.

Miss Winthrop was a glass of seltzer that had been pumped full of too many bubbles. Even if you skinned your knee or something, she'd say, “Oh, darling, there's no need to cry!” with a huge grin on her face, as if she enjoyed seeing you bleed. “I've got a Band-Aid right here in my purse. Isn't that fabulous luck!”

Uh, no. I didn't think I was lucky to have tripped on a rock. And she had the Band-Aids in her purse because it was her job to bring along the first-aid kit on the youth group hike.

That week in Sunday school, Miss Winthrop was talking about the apostle Peter and how he thought you should be good, kind and loving to everyone, even if it was hard. I was thinking, okay, it's just the Golden Rule. Then she read a quote from 1 Peter 3:14 that caught my attention:

But even if you do suffer for righteousness' sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled

.

That got me thinking about what Daddy had said to me in the car. And for the first time, I didn't feel guilty. I was pretty sure Peter would say being friends with Liz was right; Daddy was the one who was wrong to be afraid.

Before I could decide how I felt about that, I noticed Little Jimmy was sitting across the circle, staring at me. I hadn't spoken to him since I gave him the peach pit, and well, actually, I hadn't spoken to him then, either. I had a vague recollection of seeing him at Sunday school once or twice before, but he wasn't a regular like me. He was short, of course, and I'd always thought he was as bland as a glass of apple juice. His eyes seemed too big for his face, like a child's, and his cheeks were chubby, though the rest of him was skinny as a pole. I noticed he had a notebook clutched in one hand. Little Jimmy gave a small wave and smiled at me.

I blushed. Did he like me?

When class was over, I let the others file out first so I wouldn't run into Little Jimmy. By the time he was gone, my mother was at the door.

“Mrs. Nisbett,” Miss Winthrop said, “it's so good to see you!”

“Hello, Miss Winthrop,” said Mother. “I do hope Marlee was well behaved in class.”

“Oh, she's a doll, as always.” Miss Winthrop was the only person who ever described me as a doll. And I didn't talk in classâhow much trouble did Mother think I could get into?

“I've been hoping to run into you,” said Miss Winthrop.

“Oh, really?” asked Mother. “Why?”

“Some women and I have started a little group. A committee, actually, and we were wondering if we could convince you to join.”

Mother's smile brightened. “I'm always happy to do some volunteer work. And with things at school the way they are, well, let's just say I have plenty of time on my hands.”

“Funny you mention the schools,” said Miss Winthrop. “That's what our group's about. We're calling it the Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools, the WEC for short. Now, I know you are a teacher, so I was hoping you would join. Only costs one dollar, we'll put your name on our mailing list and you'll be informed of all our events. So what do you say?” Miss Winthrop finished breathlessly. “Will you join?”

Mother was red as she struggled to find the words. “Miss Winthrop, I'm honored, but . . . Of course, I want the schools to reopen, however . . . I'm not really sure Negroes should be going to our schools.”

“No need to worry about that,” Miss Winthrop continued smoothly. “The WEC isn't for integration or segregation, but for education.”

“Still,” said Mother, looking at the ground, “I'm afraid the answer is no.”

“Oh.” All the fizz went out of Miss Winthrop.

I hated Mother in that moment. She knew how important it was for me to have Judy come home. I thought it was important to her too. More important than who went to school where.

After a moment, Miss Winthrop's enthusiasm bubbled back. “Well, if you ever change your mind, please let me know.”

Mother glanced over at me. I pretended to be studying a Bible. No reason to let her know I'd been listening. Just hoped she didn't notice it was upside down. “I'll meet you on the front steps, Marlee,” she said, and walked out.

As soon as Mother was gone, I felt for the dollar in my pocket. Might as well add another name to my talking list. I looked over at Miss Winthrop and counted 2, 3, 5, 7 and said, “I want to join.”

It wasn't as hard as I'd expected. Miss Winthrop looked delighted, at least until she remembered my mother had just refused. “Are you sure your mother won't mind?”

“But even if you do suffer for righteousness' sake,”

I said,

“you will be blessed.”

“Thank you, Marlee,” said Miss Winthrop as she took my money. “You really are a doll.”