The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (19 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Storm activity increased by 85 percent in the second half of the sixteenth century, mostly during cooler winters. The incidence of severe

storms rose by 400 percent. From November 11 to 22, 1570, a tremendous gale moved slowly across the North Sea from southwest to northeast

at about 5 knots. The storm, remembered for generations as the All Saints

Flood, coincided with the unusually high tides of the full moon. As the

tempest progressed northeastward, heavy rains deluged the low-lying

coast. Frontal passage caused the wind to shift to the northwest. Enormous sea surges cascaded ashore, breaching dikes and flattening coastal

defenses. At Walcheren Island in the Low Countries (now in the southern

Netherlands), the dikes gave way between 4 and 5 o'clock on November

21, just as dark was gathering. By late evening, much of Rotterdam was

under water. Salt water surged into Amsterdam, Dordrecht, and other cities, drowning at least 100,000 people. In the River Ems, sea levels rose

four and a half meters above normal.

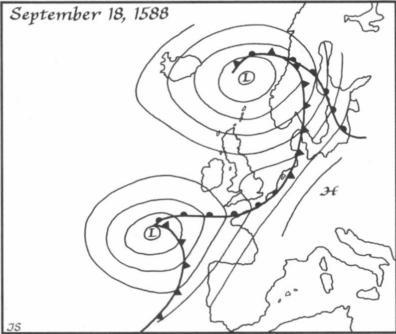

The depressions that

affected the Spanish

Armada.

Data compiled from

Hubert Lamb and Knud

Frydendahl, Historic

Storms of the North Sea,

British Isles and Northwestern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1991).

The storminess continued through the 1580s, to the discomfort of the

Spanish Armada, which endured a "very great gale at SW' off Scotland's

east coast in August 1588: "we experienced squalls, rain and fogs with

heavy sea and it was impossible to distinguish one ship from another." Sir

Francis Drake reported a "very great storm considering the time of year"

in the southern North Sea on the same day. A month later, a strong cyclonic depression advanced northeast from the region of the Azores, perhaps the descendant of a tropical hurricane on the other side of the Atlantic. The leading ships of the retreating Armada encountered the storm

in the Bay of Biscay on September 18. Three days later, the same westerly

gale blew with great fury off western Ireland, where the stragglers of the

great fleet found themselves on a hostile lee shore. "There sprang up so

great a storm on our beam with a sea up to the heavens so that the cables

could not hold, nor the sails serve us and we were driven ashore with all

three ships upon a beach covered with fine sand, shut in one side and the

other by great rocks." The Armada lost more ships to this episode of bad

weather than in any conflict with the English.17

The weather records in the logs of Armada captains have been subjected

to rigorous meteorological analysis. Modern estimates place the maximum

wind squalls as high as 40 to 60 knots, approaching hurricane strength. On several occasions, the jet stream upper wind strengths between July

and September 1588 exceeded the maxima recorded during the equivalent

months between 1961 and 1970 and, probably, over a much longer period

of the twentieth century. The unusually windy and stormy weather coincided with a strong thermal gradient caused by a vigorous southward extension of polar ice off East Greenland and Iceland and south of Cape

Farewell. Elizabethan explorer John Davis, searching for the elusive Northwest Passage, found the seas between Iceland and Greenland blocked by

ice in 1586 and 1587. Similar conditions probably continued into 1588.

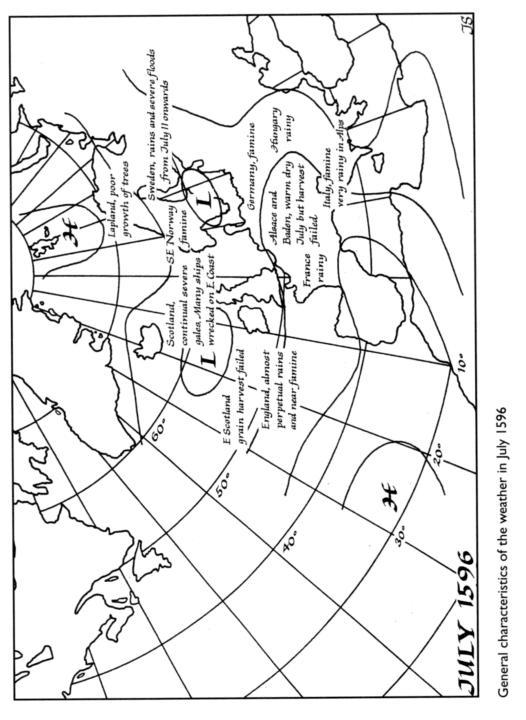

The 1590s were the coldest decade of the sixteenth century. The poor

harvests of 1591 to 1597 hit England hard three years after the triumphant defeat of the Spanish Armada. An observer wrote: "Every man

complains against the dearth of this time." Food riots erupted in many

counties, as the poor vented their anger over the enclosing of common

lands to create larger, more productive farms. The towns suffered worst.

In Barnstaple, Devon, one Philip Wyot wrote in 1596: "All this May has

not been a dry day and night.... Small quantity of corn is brought to

market [so] townsmen cannot have money for corn. There is but little

comes to market and such snatching and catching for that little and such

a cry that the like was never heard."ls In towns like Penrith in the northeast, famine mortality rose to as much as four times normal.

England's Tudor monarchs presided over 3 million subjects and were

constantly fretting about the possibility of grain shortages and famine.

England was a country of subsistence farmers, whose methods and implements of tillage had little changed from medieval times. The government

had ample cause for concern, for crop yields were low. On prime land.

two bushels of wheat were reasonably expected to yield between eight and

ten at harvest time, which left precious little margin for crop failure. The

farmers gathered "good" harvests about 40 percent of the time, with sequences of three or four good years, then a cycle of as many as four poor

harvests before a change in the weather pattern brought improved

yields.'`' Grain prices fluctuated accordingly. The price changes hit the

poor hardest of all and engendered a deep distrust of farmers among the

growing urban population. At times of crop failure and grain shortages,

suspicions of hoarding were rife. Preachers denounced hoarders from

their pulpits with a text from Proverbs: "He that witholdeth corn, the

people shall curse him," but with little effect.20 England, like the rest of Europe, still lacked a large-scale infrastructure for moving grain from

country to town, or from one region to another, to relieve local famines.

Even after the last widespread famine in southern England in 1623,

hunger was never far from the door.

Farming was just as difficult in the fledgling European colonies in North

America. Bald cypress tree rings along the Blackwater and Nottoway

rivers in southeastern Virginia may help explain why most people in the

southeastern United States speak English rather than Spanish.21 The cypresses document several severe drought cycles between 1560 and 1612,

just as Europeans were settling along the Carolina and Virginia coasts.

In 1565, Spanish colonists settled at Santa Elena on the South Carolina coast during an exceptionally dry decade. The settlement struggled

from the beginning, then succumbed to a second, even more severe

drought in 1587-9. The capital of Spanish Florida was moved to Saint

Augustine. The evacuation came as British colonists were trying to establish a settlement at Roanoke Island, North Carolina, to the north. The

Roanoke colonists were last seen by their British compatriots on August

22, 1587, at the height of the driest growing season in eight hundred

years. Even as their compatriots departed, the colony's native American

neighbors were concerned about the poor condition of their crops. The

drought persisted for two more years and created a serious food crisis

both for the local Croatan people and the colonists. Since the latter were

heavily dependent on the Croatan, this very dependence must have aggravated already serious food shortages. Many historians have criticized

the Roanoke colony for poor planning and for a seeming indifference to

how they were going to feed themselves in the face of apparent disinterest

from England. But even the best planned colony would have been challenged by the 1587-89 drought.

Further north, at Jamestown, the colonists had the bad luck to arrive at

the height of the driest seven-year period in 770 years. Of the original

104 colonists who came in 1607, only 38 were still alive a year later. No

fewer than 4,800 of the 6,000 settlers who arrived between 1607 and

1625 perished, many of them of malnutrition in the early years of the set Clement. Like their predecessors at Roanoke, the colonists were expected

to live off the land and off trade and tribute from the Indians, a way of

life that made them exceptionally vulnerable during unusually dry years.

They also suffered from water shortages when the drought drastically reduced river levels. Jamestown's archives make frequent references to the

foul drinking water and the illnesses caused by consuming it, especially

before 1613, when the drought ended.

In 1600, hunger was still a familiar threat to anyone cultivating the

soil, whether European peasant or English colonist on the edge of North

America. But the first stirrings of an agricultural revolution were underway, stimulated by explosive city growth.

THE END OF

THE "FULL WORLD"

They are made up of many small terminal moraines, laid against

and on top of each other, as is clearly shown in instances where

individual moraines lie spread out in a series one behind another, with concentrically curving crests. They record for each

glacier many repeated advances, all of approximately the same

magnitude. How many centuries of glacial oscillation are represented by these moraine accumulations it is difficult to estimate.

-Francois Matthes, "Report of Committee on Glaciers, " 1939