The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (20 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

The vines look as if they had been swept by fire. The poor

people are obliged to use their oats to make bread. This winter

they will have to live on oats, barley, peas, and other vegetables.

-A government official at Limousin, France,

October 18, 1692

will always remember the sights, smells, and sounds of subsistence agriculture in Africa-rows of women hoeing newly cleared woodland, the

will always remember the sights, smells, and sounds of subsistence agriculture in Africa-rows of women hoeing newly cleared woodland, the

scent of wood smoke and the hazy, ash-filled autumn skies, the endless

thumping of wooden pestles pounding grain for the evening meal. I recall

leisurely conversations by the fire or sitting in the shade of a hut, the talk

of rain and hunger, of scarce years, of plentiful times when grain bins burst

with maize and millet. The memories of October are the most vivid of all:

the countryside shimmering under brutal, escalating heat, the great clouds

massing on the afternoon horizon, anxious women watching for rain that

never seemed to fall. When the first showers finally arrived with their marvelous, pungent scent of wet earth, the people planted their maize and

waited for more storms. Some years there was no rain until December, and

the crops withered in the fields. Stored grain ran out in early summer and

the people faced scarcity. The specter of hunger was always in the air, never

forgotten. I received a firsthand lesson in the harsh realities of subsistence

farming, the brutal ties between climatic shifts and survival.

Surprisingly few archaeologists and historians have had a chance to observe subsistence farming at firsthand, which is a pity, for they sometimes fail to appreciate just how devastating a cycle of drought or heavy rainfall,

or unusual cold or warmth, can be. Like medieval farmers, many of today's subsistence agriculturalists in Africa and elsewhere have virtually no

cushion against hunger. They live with constant, often unspoken, environmental stress. The same was true in Europe at the end of the sixteenth

century, where well over 80 percent of the population was engaged in

subsistence agriculture, by definition living barely above subsistence level,

and at the complete mercy of short-term climatic shifts. The five centuries of the Little Ice Age were defined by these shifts: short periods of

relatively stable temperatures were regularly punctuated by markedly

colder or wetter conditions that brought storms, killing frosts, greater

storminess, and cycles of poor harvests. While Europe's subsistence farmers muddled by in good years, such sudden changes brought great stress

to communities and growing cities that were on the economic margins in

the best of times. These stresses were not only economic; inevitably they

were political and social as well.

Until recently, historians have tended to discount short-term climate

change as a factor in the development of preindustrial European civilization, partly because we lacked any means of studying annual or even

decadal climatic variations. French scholar Le Roy Ladurie argued that

the narrowness in temperature variations and the autonomy of human

phenomena that coincided with them in time made it impossible to establish any causal link. He reflected a generally held view, with only a few

dissenters, among them the English climatologist Hubert Lamb, who was

convinced climate and human affairs were related and was much criticized for saying so. I The ghosts of environmental determinism-discredited assumptions of three-quarters of a century ago that invoked climatic

change as the primary cause of the first agriculture, the emergence of the

world's first civilizations, and other major developments-still haunt

scholarly opinion. Environmental determinism is an easy charge to level,

especially if one is unaware of the subtle effects of climatic change.

Today, no one seriously considers that climate change alone caused

such major shifts in human life as the invention of agriculture. Nor do

they theorize that the climatic shifts of the Little Ice Age were responsible

for the French or Industrial revolutions or the Irish potato famine of the

1840s. But the spectacular advances of paleoclimatology now allow us to look at short-term climatic change in terms of broad societal responses to

stress, just as archaeologists have done with much earlier societies. Climate variability leading to harvest failures is just one cause of stress, like

war or disease, but we delude ourselves if we do not assume it is among

the most important-especially in a society like that of preindustrial Europe, that devoted four-fifths of its labor just to keeping itself fed.

Observing subsistence farming at firsthand is a sobering experience, especially if you have spent all your life buying food in supermarkets. You

learn early on that human beings are remarkably adaptable and ingenious

when their survival depends on it. They develop complex social mechanisms and ties of obligation for sharing food and seed, diversify their

crops to minimize risk, farm out their cattle to distant relatives to combat

epidemic disease. These qualities of adaptability and opportunism came

to the fore in sixteenth- to eighteenth-century Europe, when adequate

food supplies in the face of changeable weather conditions became a

pressing concern. A slow agricultural revolution was the result.

The revolution began in the Low Countries and took root in Britain

by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in France as a whole much

later, and in Ireland as a form of hazardous monoculture based on the

potato.2 The historical consequences were momentous-in England,

food to feed the burgeoning population of the Industrial Revolution,

along with widespread social decay and disorganization; in France, a slow

decline in peasant living standards, bringing widespread fear and unrest

at a time of political and social uncertainty; and in Ireland, catastrophic

famine that killed over a million people when blight destroyed its staple

crop and Britain neglected its humanitarian responsibilities.

The severe weather of the 1590s marked the beginnings of the apogee

of the Little Ice Age, a regimen of climatic extremes that would last over

two centuries. There were spells of unusual heat and of record cold, like

the winter of 1607, when savage frosts split the trunks of many great trees

in England. Atmospheric patterns changed too, as the polar ice cap expanded, anticyclones persisted in the north, and depression tracks with

their mild westerlies shifted southward. These anticyclones brought many

weeks of northeasterly winds, as opposed to the prevailing southwesterlies

experienced by earlier generations. Dutch author Richard Verstegan remarked in 1605 how retired skippers in the Netherlands remembered that "they have often noted the voyage from Holland to Spayne to be

shorter by a day and a halfe sayling than the voyage from Spayne to Holland."; In the century that followed, profound changes in European life

were shaped, in part, by the coldest weather in seven hundred years.

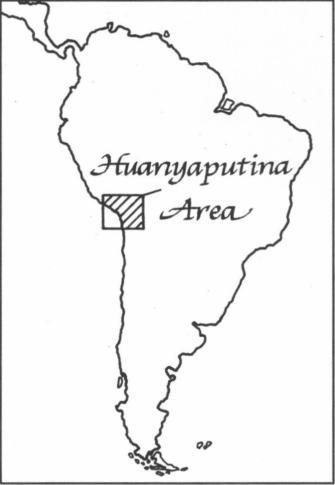

The seventeenth century literally began with a bang. Between February

16 and March 5, 1600, a spectacular eruption engulfed the 4,800meter Huanyaputina volcano seventy kilometers east of Arequipa in

southern Peru.4 Huanyaputina hurled massive rocks and ashy debris

high into the air. Volcanic ash fell over an area of at least 300,000

square kilometers, cloaking Lima, La Paz and Arica, and even a ship

sailing in the Pacific 1,000 kilometers to the west. During the first

twenty-four hours alone, over twenty centimeters of sand-sized ash fell

on Arequipa, causing roofs to collapse. Ash descended for ten days,

turning daylight into gloom. At least 1,000 people died, 200 of them in

small communities near the volcano. Lava, boulders, and ash formed

enormous lakes in the bed of the nearby Rio Tambo. The water burst

through and flooded thousands of hectares of farmland, rendering it

sterile and unproductive. Many ranches lost all their cattle and sheep.

The local wine industry was devastated.

The scale of the Huanyaputina eruption rivaled the Krakatau

explosion of 1883 and the Mount Pinatubo event in the Philippines in

1991. The volcano discharged at least 19.2 cubic kilometers of fine sediment into the upper atmosphere. The discharge darkened the sun

and moon for months and fell to earth as far away as Greenland and the

South Pole. Fortunately for climatologists, the fine volcanic glass-powder

from Huanyaputina is highly distinctive and easily identified in ice

cores. It is found at high levels in South Pole ice layers dated to

1599-1604. The signal is also present, though less distinct, in Greenland ice cores. The sulphate levels are such that we know that the

amount of sediment thrust into the stratosphere was twice that of

Mount Pinatubo and about 75 percent of the vast Mount Tambora

eruption of 1815, probably the greatest sulfur-producing event of the

Little Ice Age.

Huanyaputina ash played

havoc with global climate.5

The summer of 1601 was

the coldest since 1400

throughout the northern

hemisphere, and among the

coldest of the past 1,600

years in Scandinavia, where

the sun was dimmed by constant haze. Summer sunlight

was so dim in Iceland that

there were no shadows. In

central Europe, sun and

moon were "reddish, faint,

and lacked brilliance." Western North America lived

through the coldest summer

of the past four hundred

years, with below-freezing

temperatures during the

maize growing season in

Map of Huanyaputina area, Peru

many areas. In China, the sun was red and dim, with large sunspots.

Volcanic events produced at least four more major cold episodes dur-

ing the seventeenth century, which is remarkable for having at least six

climatically significant eruptions.6 None rivaled summer 1601, but

1641-43, 1666-69, 1675, and 1698-99 experienced major cold spikes

connected with volcanic activity. The identity of these eruptions remains unknown except for that of January 4, 1641, when Mount

Parker on Mindanao in the Philippines erupted with a noise "like musketry." Wrote an anonymous Spanish eyewitness: "By noon we saw a

great darkness approaching from the south which gradually spread over

the entire hemisphere. . . . By 1 pm we found ourselves in total night

and at 2 pm in such profound darkness that we could not see our hands

before our eyes."7 A nearby Spanish flotilla lit lanterns at midday and

frantically shoveled ash off its decks, fearing in the darkness "the Judgement Day to be at hand." The dust from the eruption affected temperatures worldwide.