The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition (24 page)

Read The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition Online

Authors: Daniel J. Wallace

Why are women disproportionally afflicted with SLE? Do men have milder or

more severe cases than women? Are there hormonal imbalances unique to lupus?

Is there any relationship between the disease and our endocrine (hormonal)

tissues, such as the thyroid and adrenal glands? Since it was first observed that 90 percent of lupus patients are women and 90 percent of these patients develop the disease during their childbearing years, it seemed logical to study hormonal relationships in SLE. This section reviews these approaches.

The use of hormonal interventions such as birth control pills and estrogens,

among others, is discussed in Chapters 13 and 28.

UNDERSTANDING HORMONES

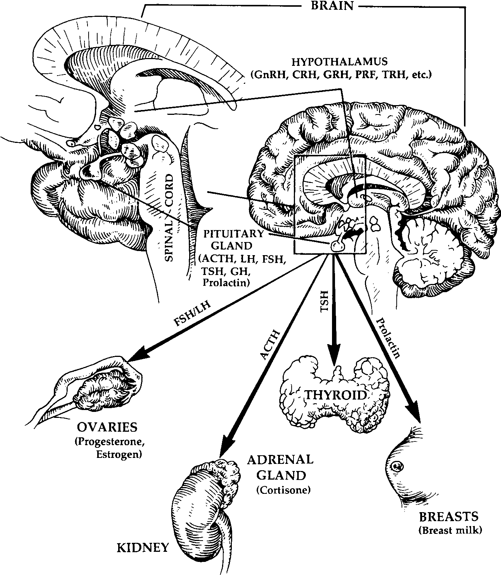

A hormone is a chemical made by one organ that is transported in the blood to

another organ, where it carries out its function. There is an area in the brain known as the hypothalamus, which is responsible for manufacturing a group of

chemicals known as

releasing hormones

. When these chemicals travel a short distance to another area called the anterior pituitary gland, the releasing hormones promote the production of

stimulating hormones

. These stimulating hormones are secreted into the bloodstream and travel to the peripheral endocrine

glands or other body organs.

For example, the hypothalamus makes thyroid-releasing hormone, which in-

duces pituitary production of thyroid-stimulating hormone, which, in turn,

prompts the thyroid gland to make thyroid hormone. Other hormones derived

by similar mechanisms include cortisol, made by the adrenal gland, and prolac-

tin, which is made in the anterior pituitary and results in the secretion of breast milk. The female reproductive organs produce estrogen and progesterone; male

hormones are called

androgens

, with testosterone being the most important.

Figure 17.1 illustrates these hormonal pathways.

[128]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

Fig. 17.1.

Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormonal Pathways

HOW IS THE ENDOCRINE SYSTEM ALTERED

IN SYSTEMIC LUPUS?

What happens to sex hormones in lupus patients? Sex hormones act on the

immune system in three ways. First of all, they stimulate the central nervous

system to release immunoregulatory chemicals. Second, they regulate the pro-

duction of cytokines (Chapter 5). Finally, sex hormones stimulate endocrine

glands to release other hormones, such as prolactin, in women.

Estrogens, or female hormones, can promote autoimmunity, and this can in-

directly increase inflammation, whereas androgens (male hormones) generally

What about Hormones?

[129]

suppress autoimmunity. Estrogens increase the production of autoantibodies, in-

hibit natural killer cell function, and induce atrophy of the thymus gland. Further, in SLE, estrogens are metabolized differently. Due to an abnormality in a chemical pathway (called 16 alpha-hydroxylation), lupus patients have excess

levels of 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone and estriol metabolites. Males with lupus have lower-than-normal levels of testosterone and other androgens.

IS THERE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN MEN AND WOMEN

WITH SYSTEMIC LUPUS?

How do males with SLE fare? This information has been surprisingly difficult

to ascertain. For instance, in order to study outcomes in a scientifically acceptable fashion, a large group of men with SLE must be followed closely for at

least 5 and preferably 10 years. Since 90 percent of those with SLE are women,

this requires studying several hundred patients. Interestingly, no studies suggest that males have a better prognosis. Published reports are evenly divided between males having a similar outcome to that of females and those suggesting that

men have a poorer prognosis.

If SLE is aggravated by female hormones, why might males fare worse? This

question has stumped the best and brightest rheumatologists for years. One pos-

sible answer recalls a fascinating survey performed in the 1960s that would be

extremely difficult to repeat in today’s research environment. In that report, the gender of fetuses from women with SLE who miscarried was tabulated, and the

majority were males. This suggests that male fetuses with a lupus gene are more likely not to be born, which may explain why there are so few men with SLE.

On the other hand, a rare chromosomal disorder known as

Klinefelter’s syn-

drome

provides investigators with contradictory clues. A normal female carries two X chromosomes (XX) and a normal male one X and one Y (or male)

chromosome (XY). Individuals with Klinefelter’s are men who carry an extra

X chromosome (XXY). It has been suggested that Klinefelter’s patients have an

increased incidence of SLE and that this is directly related to female hormone

excess.

MENSTRUAL PROBLEMS IN SLE

One of the most frequently asked questions I encounter deals with the relation-

ship between lupus and menstruation.

Amenorrhea

, or the absence of menstruation, is observed in 15 to 25 percent of women with SLE between the ages of

15 and 45 and can be related to prior chemotherapy or severe disease activity.

Irregular periods are not uncommon. For example, nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increase bleeding, and changes in corticosteroid

doses or steroid shots into joints or muscles can alter menstrual cycles. A preg-

[130]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

nancy test should always be performed before any medical treatment directed

toward amenorrhea or menstrual irregularities is initiated.

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

may be more severe in SLE, and the majority of women with lupus report a mild premenstrual flare in their musculoskeletal

symptoms. The onset of

menopause

is associated with less SLE activity.

THYROID DISEASE

Vanessa was feeling achy and under a lot of stress. When she visited her

doctor, he decided to take an ANA test, which came back positive, and he

told her she might have lupus. She was very edgy and couldn’t focus on

any task for more than 3 minutes. She increasingly became aware of pal-

pitations and was always turning up the air conditioning. A rheumatologist

was consulted, who confirmed that the ANA was positive, but it was in a

low-level speckled pattern. The blood panel also included other autoanti-

bodies, and her thyroid antibodies were markedly elevated. Blood testing

showed that she had elevated thyroid function and was hyperthyroid. A

diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis was made; Vanessa did not have lupus.

When antithyroid medication failed to suppress her symptoms adequately,

she was given radioactive iodine to drink, which prevented the gland from

making thyroid and allowed her to feel normal again. She is now main-

tained on a low dose of thyroid replacement.

The thyroid gland in the neck helps regulate our metabolism and it affects

how we feel by controlling the production of thyroid hormone. Thyroid-related

symptoms—such as fatigue, palpitations, fevers, being too hot or too cold, and

joint aches—can often be mistaken for SLE.

Autoimmune disease of the thyroid is characterized by detectable levels of

antithyroid antibodies in the blood. Clinically manifested as

Graves’ disease

or

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

, autoimmune thyroid disease initially appears as hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and ultimately develops into hypothyroidism

(underactive thyroid). Approximately 10 percent of lupus patients have thyroid

antibodies, and autoimmune thyroiditis occasionally coexists with SLE. Many

of these individuals also have Sjo¨gren’s syndrome. Conversely, many people

like Vanessa with primary autoimmune thyroid disease have positive ANA tests

without evidence of lupus.

Whether or not autoimmune thyroiditis is present, some 1 to 15 percent of

those with SLE studied at any point are hyperthyroid and 1 to 10 percent are

hypothyroid. In other words, thyroid abnormalities are commonly noted in lupus

and are related to antithyroid antibodies about half of the time.

DIABETES MELLITUS

The most common cause of diabetes in SLE patients is corticosteroid therapy.

Steroids raise blood sugars, and the risk of developing diabetes depends on how

What about Hormones?

[131]

much prednisone the patient has been taking and for how long. Diabetes some-

times disappears when steroid doses are lowered or discontinued.

The islet cells of the pancreas are endocrine tissues responsible for producing insulin. Interestingly, many individuals with juvenile diabetes (called type I) have positive ANAs even though lupus is uncommon in this group of patients.

THE ADRENAL GLAND

Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH)

in the hypothalamus stimulates the production of

adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

in the pituitary, which induces the secretion of various types of cortisone (steroids) by the adrenal gland (see Figure 17.1). The adrenal gland can be affected directly and indirectly in systemic lupus.

The direct effects include an autoimmune inflammatory process known as

autoimmune adrenalitis

, whose concurrence rate with SLE has not been determined. In addition, the

antiphospholipid syndrome

(see Chaper 21) may result in clots to the adrenal gland’s blood supply, which leads to infarction, or death of adrenal tissue.

The administration of oral (exogenous) corticosteroids suppresses internal (en-

dogenous) secretions of steroids from the adrenal gland. The normal adrenal

gland makes the equivalent of 7.5 milligrams of prednisone daily. Higher oral

steroid doses turn off the adrenal gland; when steroid doses are decreased below 7.5 milligrams, the gland is supposed to resume steroid production. However,

when one has been on corticosteroids for a prolonged time, the adrenal response is sluggish and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, such as fatigue and aching,

may become evident. When the adrenal gland does not make enough cortisone,

symptoms of

adrenal insufficiency

become manifest and can mimic a lupus flareup. See Chapter 27.

WHAT ABOUT PROLACTIN—THE BREAST HORMONE?

Prolactin

is a hormone that provides the stimulus needed to produce breast milk.

Over the last few years, several investigators have documented that a dispro-

portionate number of lupus patients have elevated prolactin blood levels. One

group of researchers has gone further and suggested that a drug known as brom-

ocriptine (Parlodel), which blocks prolactin, may help lupus patients. These hy-potheses have not yet been confirmed, and lupus patients of mine who have

taken the drug have not improved.

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION: DO LUPUS PATIENTS

HAVE A PROBLEM?

It’s rare for women with lupus to be unable to enjoy sexual intercourse. Female sexual dysfunction because of disease activity is unusual in SLE. The two well-

[132]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

established exceptions are vaginal dryness from Sjo¨gren’s syndrome and vaginal ulcerations, which are rare compared to oral or nasal ulcerations. Both of these conditions can result in painful intercourse. Vaginal dryness is managed with

lubricants and ulcerations with a hydrocortisone ointment. Physiologic sexual

problems unique to males with lupus have not been reported.

Sometimes women with avascular necrosis or other destructive changes in the

hip have difficulty spreading their legs apart during lovemaking. Until corrective surgery can alleviate this, lupus patients and their partners are urged to use

alternatives to the missionary (man on top) position, such as the woman being

on top, or rear entry. (In Chapter 25, psychological and emotional aspects of

sexuality are discussed in more detail.)

DO LUPUS PATIENTS HAVE ANTIBODIES

TO SEX HORMONES?

Even though sexual problems of a physiologic nature are unusual, many lupus

patients have antibodies to reproductive hormones. As many as 30 percent of

women with lupus have antiestrogen and antiovarian antibodies in their blood.

The presence of the antibodies does not really matter, and has nothing to do

with fertility, except that they are more common in patients taking birth-control pills. Males with SLE have an increased prevalence of antisperm antibodies.