The Lying Stones of Marrakech (8 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

You should know that while I was in Rome, Signor Cioli visited the Duchess [Cesi's widow] several times, and that she gave him, at his departure, several pieces of the fossil wood that originates near Acquaspartaâ¦. He wanted to know where it was found, and how it was generated ⦠for he noted that Prince Cesi, of blessed memory, had planned to write about it. The Duchess then asked me to write something about this, and I have done so, and sent it to Signor Cioli, together with a package of several pieces of the wood, some petrified, and some just beginning to be petrified.

This fossil wood had long vexed and fascinated the Lynxes. Stelluti had described the problem to Galileo in a letter of August 23, 1624, written just before the Lynxes' convention and the fateful series of events initiated by Stelluti's microscopical drawings of bees, intended to curry favor with the new pope.

Our lord prince [Cesi] kisses your hands and is eager to hear good news from you. He is doing very well, despite the enervating heat, which does not cause him to lose any time in his studies and most beautiful observations on this mineralized wood. He has discovered several very large pieces, up to eleven palms [of the human hand, not the tree of the same name] in diameter, and others filled with lines of iron, or a material similar to ironâ¦. If you can stop by here on your return to Florence, you can see all this wood, and where it originates, and some of the nearby mouths of fire [steaming volcanic pits near Acquasparta that played a major role in Stelluti's interpretation of the wood]. You will observe all this with both surprise and enthusiasm.

We don't usually think of Galileo as a geologist or paleontologist, but his catholic (with a small

c

!) interests encompassed everything that we would now call science, including all of natural history. Galileo took his new telescope to his first meeting of 1611 with Cesi and the Lynxes, and the members all became enthralled with Galileo's reconstructed cosmos. But he also brought, to the same meeting, a curious stone recently discovered by some alchemists in Bologna, called the

lapis Bononensis

(the Bologna stone), or the “solar sponge”âfor the rock seemed to absorb, and then reflect, the sun's light. The specimens have been lost, and we still cannot be certain about the composition or the nature of Galileo's stone (found in the earth or artificially made). But we do know that the Lynxes became entranced by this geological wonder. Cesi,

committed to a long stay at his estate in Acquasparta, begged Galileo for some specimens, which arrived in the spring of 1613. Cesi then wrote to Galileo: “I thank you in every way, for truly this is most precious, and soon I will enjoy the spectacle that, until now, absence from Rome has not permitted me” (I read this quotation and information about the Bologna stone in Paula Findlen's excellent book,

Processing Nature

, University of California Press, 1994).

A comparison of title pages for Galileo's book on sunspots and Stelluti's treatise on fossil wood, with both authors identified as members of the Lynx society

.

Galileo then took a reciprocal interest in Cesi's own geological discoveryâthe fossil wood of Acquasparta; so Stelluti's letters reflect a clearly shared interest. Cesi did not live to publish his controversial theories on this fossil wood. Therefore, the ever-loyal Stelluti gathered the material together, wrote his own supporting text, engraved thirteen lovely plates, and published his most influential work (with the possible exception of those earlier bees) in 1637:

Trattato del legno fossile minerale nuovamente scoperto, nel quale brevemente si accenna la varia e mutabil natura di detto legno, rappresentatovi con alcune figure, che mostrano il luogo dove nasce, la diversita dell'onde, che in esso si vedono, e le sue cosi varie, e maravigliose forme

âa tide almost as long as the following text (Treatise on newly discovered fossil mineralized wood, in which we point out the variable and mutable

nature of this wood, as represented by several figures, which show the place where it originates, the diversity of waves [growth lines] that we see in it, and its highly varied and marvelous forms).

The title page illustrates several links with Galileo. Note the similar design and same publisher (Mascardi in Rome) for the two works. Both feature the official emblem of the Lynxesâthe standard picture of the animal (copied from Gesner's 1551 compendium), surrounded by a laurel wreath and topped by the crown of Cesi's noble family. Both authors announce their affiliation by their nameâthe volume on sunspots by Galileo Galilei Linceo, the treatise on fossil wood by Francesco Stelluti Accad. Linceo. The ghosts of Galileo's tragedy also haunt Stelluti's title page, for the work bears a date of 1637 (lower right in Roman numerals), when Galileo lived in confinement at Arcetri, secretly writing his own last book. Moreover, Stelluti dedicates his treatise quite obsequiously “to the most eminent and most revered Signor Cardinal Francesco Barberini” (in type larger than the font used for Stelluti's own name), the nephew of the pope who had condemned Galileo, and the man who had refused Stelluti's invitation to lead (and save) the Lynxes after Cesi's death.

But the greatest and deepest similarity between Galileo's book on sunspots and Stelluti's treatise on fossil wood far transcends any visual likenesses, and resides instead in the nature of a conclusion, and a basic style of rhetoric and scientific procedure. Galileo presented his major discussion of Saturn in his book on sunspots (as quoted earlier in this essay)âwhere he stated baldly that an entirely false interpretation must be correct because he had observed the phenomenon with his own eyes. Stelluti's treatise on fossil wood presents a completely false (actually backward) interpretation of Cesi's discovery, and then uses exactly the same tactic of arguing for the necessary truth of his view because he had personally observed the phenomena he described!

Despite some practical inconveniences imposed by ruling powers committed neither to democracy nor to pluralismâone might, after all, end up burned like Bruno, or merely arrested, tried, convicted, and restricted like Galileoâthe first half of the seventeenth century must rank as an apex of excitement for scientists. The most fundamental questions about the structure, meaning, and causes of natural phenomena all opened up anew, with no clear answers apparent, and the most radically different alternatives plausibly advocated by major intellects. By inventing a simple device for closer viewing, Galileo fractured the old conception of nature's grandest scale. Meanwhile, on earth, other scientists raised equally deep and disturbing questions about the very nature of matter and the basic modes of change and causality.

The nascent science of paleontology played a major role in this reconstruction of realityâprimarily by providing crucial data to resolve the two debates that convulsed (and virtually defined) the profession in Stelluti and Galileo's time (see chapter 1 for more details on this subject):

1. What do fossils represent? Are they invariably the remains of organisms that lived in former times and became entombed in rocks, or can they be generated inorganically as products of formative forces within the mineral kingdom? (If such regular forms as crystals, and such complex shapes as stalactites, can arise inorganically, why should we deny that other petrified bodies, strongly resembling animals and plants, might also originate as products of the mineral kingdom?)

2. How shall we arrange and classify natural objects? Is nature built as a single continuum of complexity and vitality, a chain of being rising without a gap from dead and formless muds and clays to the pinnacle of humanity, perhaps even to God himself? Or can natural objects be placed into sharply separated, and immutably established, realms, each defined by such different principles of structure that no transitional forms between realms could even be imagined? Or in more concrete terms: does the old tripartite division of mineral, vegetable, and animal represent three loosely defined domains within a single continuum (with transitional forms between each pair), or a set of three utterly disparate modes, each serving as a distinct principle of organization for a unique category of natural objects?

Cesi had always argued, with force and eloquence, that the study of small objects on earth could yield as much reform and insight as Galileo's survey of the heavens. The microscope, in other words, would be as valuable as the telescope. Cesi wrote:

If we do not know, collect, and master the smallest things, how will we ever succeed in grasping the large things, not to mention the biggest of all? We must invest our greatest zeal and diligence in the treatment and observation of the smallest objects. The largest of fires begins with a small spark; rivers are born from the tiniest drops, and grains of sand can build a great hill.

Therefore, when Cesi found a puzzling deposit of petrified wood near his estate, he used these small and humble fossils to address the two great questions

outlined aboveâand he devised the wrong answer for each! Cesi argued that his fossil wood had arisen by transformation of earths and clays into forms resembling plants. His “wood” had therefore been generated from the mineral kingdom, proving that fossils could form inorganically. Cesi then claimed that his fossils stood midway between the mineral and vegetable kingdoms, providing a smooth bridge along a pure continuum. Nature must therefore be constructed as a chain of being. (Cesi had strongly advocated this position for a long time, so he can scarcely be regarded as a dispassionate or disinterested observer of fossils. His botanical classification, eventually published by Stelluti in 1651, arranged plants in a rising series from those he interpreted as most like minerals to forms that he viewed as most like animals.) Since Cesi could not classify his fossils into any conventional kingdom, he awarded them a separate name for a novel realm between minerals and plantsâthe Metallophytes.

Stelluti, playing his usual game of follow the leader, devoted his 1637 treatise to supporting Cesi's arguments for the transitional status of metallophytes and their origin from the mineral kingdom as transmuted earths and clays. The fossils may look like plants, but they originate from heated earths of the surrounding countryside (where subterranean magmas boil the local waters, thus abetting the conversion of loose earth to solid metallophyte). Stelluti concludes:

The generation of this wood does not proceed from the seed or root of any plant, but only from a kind of earth, very much like clay, which little by little becomes transmuted to wood. Nature operates in such a manner until all this earth is converted into that kind of wood. And I believe that this occurs with the aid of heat from subterranean fires, which are found in this region.

To support this conclusion, Stelluti presented the following five basic arguments:

1. The fossil wood, generated from earth, only assumes the forms of tree trunks, never any other parts of true plants:

It is clear that this wood is not born from seeds, roots or branches, like other plants, because we never find pieces of this wood with roots, or branches, or nerves [internal channels for fluids], as in other [truly vegetable] wood and trees, but only simple trunks of varied form.

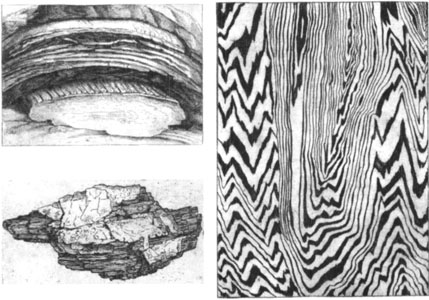

Three figures of fossil wood from Stelluti's treatise of 1637

.

2. The fossil trunks are not rounded, as in true trees, but rather compressed to oval shapes, because they grow

in situ

from earths flattened by the weight of overlying sediments (see the accompanying reproduction of Stelluti's figure):

I believe that they adopt this oval shape because they must form under a great mass of earth, and cannot grow against the overlying weight to achieve the circular, or rather cylindrical, form assumed by the trunks of true trees. Thus, I can securely affirm that the original material of this wood must have been earth of a clayey composition.

3. Five of Stelluti's plates present detailed drawings of growth lines in the fossil wood (probably done, in part, with the aid of a microscope). Stelluti's argument for these inner details of structure follows his claim for the outward form of entire specimens: the growth lines form wandering patterns reflecting irregular pathways of generation from earth, following limits imposed by the weight of overlying sediments. These lines never form in regular concentric circles, as in true trees. Stelluti therefore calls them

onde

, or “waves,” rather than growth lines: