The Lying Stones of Marrakech (12 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

The availability of this alternative view, based on the theatrical idol of Neoplatonism, set the primary context for seventeenth-century discussions about hysteroliths. Scholars could hardly ask: “what animal makes this shape as its mold?” when they remained stymied by the logically prior, and much more important, question: “are hysteroliths remains of organisms or products of the mineral kingdom?” This framework then implied another primary questionâ also posed as a dichotomy (and thus illustrating the continuing intrusion of tribal idols as well)âamong supporters of an inorganic origin for hysteroliths: if vulva stones originate within the mineral kingdom, does their resemblance to female genitalia reveal a deep harmony in nature, or does the similarity arise by accident and therefore embody no meaning, a mode of origin that scholars of the time called

lusus naturae

, a game or sport of nature?

To cite examples of these two views from an unfamiliar age, Olaus Worm spoke of a meaningful correspondence in 1665, in the textual commentary to his first pictorial representation of hysterolithsâalthough he attributed the opinion to someone else, perhaps to allay any suspicion of partisanship:

These specimens were sent to me by the most learned Dr.J.D.Horst, the archiater [chief physician] to the most illustrious Landgrave of Darmstadtâ¦. Dr.Horst states the following about the strength of these objects: these stones are, without doubt, useful in treating any loosening or constriction of the womb in females. And I think it not silly to believe, especially given the form of these objects [I assume that Dr.Horst refers here to hysteroliths that resemble female parts on one side and male features on the other] that, if worn suspended around the neck, they will give strength to people experiencing problems with virility, either through fear or weakness, thus promoting the interests of Venus in both sexes

[Venerem in utroque sexu promovere]

.

But Worm's enthusiasm did not generate universal approbation among scholars who considered an origin for hysteroliths within the mineral kingdom. Anselm de Boot, in the 1644 French translation of his popular compendium on fossils (in the broad sense of “anything found underground”), writes laconically:

“Elles n'ont aucune usage que je sçache”

(they have no use that I know).

By the time that J.C. Kundmannâwriting in vernacular German and living in Bratislava, relatively isolated from the “happening” centers of European intellectual lifeâpresented the last serious defense for the inorganic theory of

fossils in 1737, the comfortable rug of Neoplatonism had already been snatched away by time. (The great Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher had written the last major defense of Neoplatonism in paleontology in 1664, in his

Mundus subter-raneus

, or

Underground World)

Kundmann therefore enjoyed little intellectual maneuvering room beyond a statement that the resemblances to female genitalia could only be accidentalâfor, after all, he argued, a slit in a round rock can arise by many mechanical routes. In a long chapter devoted to hysteroliths, Kundmann allowed that hysteroliths might be internal molds of shells, and even admitted that some examples described by others might be so formed. But he defended an inorganic origin for his own specimens because he found no evidence of any surrounding shell material: “an excellent argument that these stones have nothing to do with clamshells, and must be considered as

Lapides sui generis”

(figured stones that arise by their own generationâa “signature phrase” used by supporters of an inorganic origin for fossils).

3.

Idols of the Marketplace in the Eighteenth Century

. Reordering the language of classification to potentiate the correct answer.

As stated above, the inorganic theory lost its best potential rationale when the late-seventeenth-century triumph of modern scientific styles of thinking (the movement of Newton's generation that historians of science call

“the

scientific revolution”) doomed Neoplatonism as a mode of acceptable explanation. In this new eighteenth-century context, with the organic theory of fossils victorious by default, a clear path should have opened toward a proper interpretation of hysteroliths.

But Bacon, in his most insightful argument of all, had recognized that even when old theories (idols of the theater) die, and when deep biases of human nature (idols of the tribe) can be recognized and discounted, we may still be impeded by the language we use and the pictures we drawâidols of the marketplace, where people gather to converse. Indeed, in eighteenth-century paleontology, the accepted language of description, and the traditional schemes of classification (often passively passed on from a former Neoplatonic heritage without recognition of the biases thus imposed) established major and final barriers to solving the old problem of the nature of hysteroliths.

At the most fundamental level, remains of organisms had finally been separated as a category from other “things in rocks” that happened to look like parts or products of the animal and vegetable kingdom. But this newly restricted category commanded no name of its own, for the word

fossil

still covered everything found underground (and would continue to do so until the early

nineteenth century). Scholars proposed various solutionsâfor example, calling organic remains “extraneous fossils” because they entered the mineral kingdom from other realms, while designating rocks and minerals as “intrinsic fossils”â but no consensus developed during the eighteenth century. In 1804, the British amateur paleontologist James Parkinson (a physician by day job, and the man who gave his name to Parkinson's disease), recognizing the power of Bacon's idols of the marketplace and deploring this linguistic impediment, argued that classes without names could not be properly explained or even conceptualized:

But when the discovery was made, that most of these figured stones were remains of subjects of the vegetable and animal kingdoms, these modes of expression were found insufficient; and, whilst endeavoring to find appropriate terms, a considerable difficulty arose; language not possessing a sign to represent that idea, which the mind of man had not till now conceived.

The retention of older categories of classification for subgroups of fossils imposed an even greater linguistic restriction. For example, so long as some paleontologists continued to use such general categories as

lapides idiomorphoi

(“figured stones”), true organic remains would never be properly distinguished from accidental resemblances (a concretion recalling an owl's head, an agate displaying in its color banding a rough picture of Jesus dying on the cross, to cite two actual cases widely discussed by eighteenth-century scholars). And absent such a separation, and a clear assignment of hysteroliths to the animal kingdom, why should anyone favor the hypothesis of brachiopod molds, when the very name

vulva stone

suggested a primary residence in the category of accidentsâ

for no one had ever argued that hysteroliths could be actual fossilized remains of detached parts of female bodies!

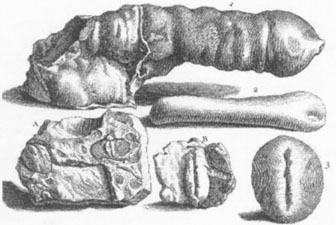

A 1755 illustration of hysteroliths on the same plate as a stalactite that accidentally resembles a penis

.

As a pictorial example, consider the taxonomic placement of hysteroliths in a 1755 treatise by the French natural historian Dezallier d'Argenville. He draws his true hysterolith (Figure A in the accompanying illustration) right next to slits in rocks that arose for other reasons (B and 3) and, more importantly, right under a stalactite that happens to look like a penis with two appended testicles. Now we know that the stalactite originated from dripping calcite in a cave, so we recognize this unusual resemblance as accidental. But if hysteroliths really belong in the same taxonomic category, why should we regard them as formed in any fundamentally different way?

When these idols of the marketplace finally receded, and hysteroliths joined other remains of plants and animals in an exclusive category of organic remainsâand when the name

hysterolith

itself, as a vestige of a different view that emphasized accidental resemblance over actual mode of origin, finally faded from useâthese objects could finally be seen and judged in a proper light for potential resolution.

Even then, the correct consensus did not burst forth all at once, but developed more slowly, and through several stages, as scientists, now and finally on the right track, moved toward a solution by answering a series of questionsâall dichotomously framed once againâthat eventually reached the correct solution by successive restriction and convergence. First, are hysteroliths molds of an organism, or actual petrified parts or wholes? Some proposals in the second category now seem far-fetchedâfor example, Lang in 1708 on hysteroliths as fossilized sea anemones of the coral phylum (colonies of some species do grow with a large slit on top), or Barrèr in 1746 on

cunnulites

(as he called them, with an obvious etymology not requiring further explanation on my part) as the end pieces of long bones (femora and humeri) in juvenile vertebrates, before these termini fuse with the main shaft in adulthood. But at least paleontologists now operated within a consensus that recognized hysteroliths as remains of organisms.

Second, are hysteroliths the molds of plants or animals, with nuts and clams as major contenders in each kingdomâand with a quick and decisive victory for the animal kingdom in this case. Third, and finally, are hysteroliths the internal molds of clams or brachiopodsâa debate that now, at the very end of the story, really could be solved by something close to pure observation, for consensus had finally been reached on what questions to ask and how they might be answered. Once enough interiors of brachiopod shells had been examinedâ

not so easy because almost all brachiopod fossils expose the outside of the shell, while few living brachiopods had been observed (for these animals live mostly in deep waters, or in dark crevices within shallower seas)âthe answer could not be long delayed.

We may close this happy tale of virtue (for both sexes) and knowledge triumphant by citing words and pictures from two of the most celebrated intellectuals of the eighteenth century. In 1773, Elie Bertrand published a classification of fossils commissioned by Voltaire himself as a guide for arranging collections. His preface, addressed to Voltaire, defends the criterion of mode of origin as the basis for a proper classificationâa good epitome for the central theme of this essay. Turning specifically to hysteroliths, Bertrand advises his patron:

There is almost no shell, which does not form internal molds, sometimes with the shell still covering the mold, but often with only the mold preserved, though this mold will display all the interior marks of the shell that has been destroyed. This is the situation encountered in hysteroliths, for example, whose origin has been debated for so long. They are the internal molds of⦠terebratulids [a group of brachiopods]. (My translation from Bertrand's French.)

But if a good picture can balance thousands of words, consider the elegant statement made by Linnaeus himself in the catalog of Count Tessin's collection that he published in 1753. The hysteroliths (Figure 2,A-D), depicted with both their male and female resemblances, stand next to other brachiopod molds that do not resemble human genitalia (Figure 1,A and B)âthus establishing the overall category by zoological affinity rather than by external appearance. In Figures 3 to 7, following, Linnaeus seals his case by drawing the fossilized shells of related brachiopods. Two pictures to guide and establish a transitionâfrom the lost and superseded world of Dezallier d'Argenville's theory of meaning by accidental resemblance to distant objects of other domains, to Linnaeus's modern classification by physical origin rather than superficial appearance.

Bacon's idols can help or harm us along these difficult and perilous paths to accurate factual knowledge of nature. Idols of the tribe may lie deep within the structure of human nature, but we should also thank our evolutionary constitution for another ineradicable trait of mind that will keep us going and questioning until we break through these constraining idolsâour drive to ask and to know. We cannot look at the sky and not wonder why we see blue. We

cannot observe that lightning kills good and bad people alike without demanding to know why. The first question has an answer; the second does not, at least in the terms that prompt our inquiry. But we cannot stop asking.