The Making Of The British Army (55 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

The Maginot concept derived from a more fundamental logic, however – or, at least, had done at the time of its conception. After the losses of the First World War France was left holding a demographic time bomb: in the 1930s there would simply not be enough conscripts to maintain the size of army which the general staff calculated it would need. But the overwhelming conclusion that the staff had drawn from the great battles of 1916 – Verdun and the Somme – was that impregnable defences could be constructed, and with a German offensive thereby halted, artillery could do the rest. Such a line of defences would also buy time for general mobilization – recall of reservists – as well as protecting Alsace-Lorraine, which had been reacquired through the Versailles Treaty. There was no longer talk in French military circles of

l’offensive à l’outrance;

this was a defensive-minded strategy, a vision of warfare along the lines of the middle years of the First World War. It was, indeed, not so different from the British perception, although until 1939 that perception had been academic since war on the Continent was – in the estimation of the cabinet – out of the question.

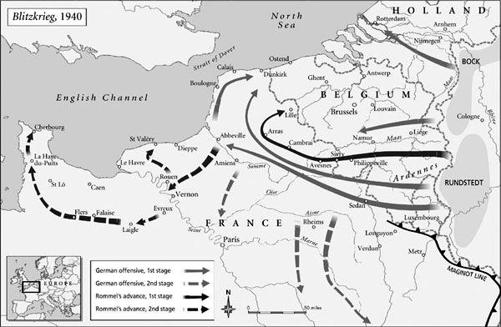

And so in May 1940, just before the Germans struck, what passed for the Anglo-French manœuvre force was waiting on the Franco-Belgian border. It did not expect to fight there, however. In the event of a German thrust into Belgium it intended sprinting across the border like an enormous Le Mans start to take up positions alongside the Belgian army on the River Dyle (Dijle), which linked the Ardennes in the south with Antwerp in the north. So sensitive were the Belgians about their neutrality, none the less, that reconnaissance of the Dyle by British and French officers had had to be done in plain clothes. It did not augur well.

*

The so-called ‘phoney war’ from 3 September 1939 (the actual declaration of hostilities) to mid-May the following year (when the Germans at last launched their offensive into the Low Countries) had been a vital breathing space for the BEF. On 23 August, Neville Chamberlain’s government had finally been disabused of any thoughts of preserving peace by – somewhat ironically – the signing of a Nazi – Soviet non-aggression pact, even while its most alarming protocols remained secret. Two days later Britain signed the Anglo-Polish treaty of mutual assistance, though in military terms it was Britain, rather than Poland, that would prove the beneficiary. On 31 August, as wearily expected, Hitler gave orders for his troops to cross the Polish frontier the following day. After expiry of the obligatory ultimatum, Chamberlain sombrely announced on the BBC: ‘I have to tell you that no such undertaking [to withdraw troops from Poland] has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.’ The air-raid sirens sounded almost immediately when a lone plane approaching London was mistaken for a bomber. But except at sea there was little immediate military action that Chamberlain could take: he was not willing to provoke retaliation by sending Bomber Command to Berlin, and it would be months – by any reckoning – before the BEF was in a position to take the offensive.

Besides making up the shortfall in equipment, the army had to address the organizational problems created by its rapid expansion, much as in 1914. At the beginning of 1939 there were 56,000 British troops in India, 14,000 men in garrisons from the West Indies to Hong Kong and 107,000 regulars in the United Kingdom. In addition there were 21,000 in the Mediterranean and Middle East, though because of the uncertainty over Italy’s intentions and Japanese expansionism in the Far East they were not available for operations in France, as they had been in 1914.

176

Yet by the end of September 160,000 troops had already crossed to France, and by the following April, just before the Germans struck, the BEF had grown to over 380,000. Even so, tanks were few and none of them were integrated with the divisions, which had only a ‘divisional cavalry regiment’ for reconnaissance equipped with the woefully inadequate Vickers light tanks armed with twin machine guns.

A good many of the officers and NCOs with Great War medals had been promoted to command and staff posts in the expanded army. In consequence, and in contrast to 1914, when only a dozen years had passed since the South African War, there was at regimental level a dearth of fighting experience, except of colonial skirmishing. The colonial experience was by no means valueless, but it did not translate automatically to the needs of the

Blitzkrieg

which was about to befall the BEF. The period of ‘sitzkrieg’, as inevitably the military wags dubbed the winter of waiting, was therefore a blessing in providing time to get the BEF trained.

Unfortunately not all its commanders were up to the job, as one of them who was – GOC (general officer commanding) II Corps, Lieutenant-General Alan Brooke (later to be Churchill’s CIGS) – explained in his memoirs:

The First World War had taken the cream of our manhood. Those that had fallen were the born leaders of men, in command of companies or battalions. It was always the best that fell by taking the lead. Those that we had lost as subalterns, captains and majors in the First World War were the very ones we were [now] short of as colonels, brigadiers and generals.

177

France had a demographic time bomb; Britain had damp powder.

The defect at brigade level and above – though nearly every one of the BEF’s generals had a DSO, and there were several VCs too – would be brutally exposed in the withdrawal to Dunkirk, but it was evident even during the ‘sitzkrieg’. It was revealed also at the regimental level, with some units appearing not to have appreciated the demands of a war of manœuvre as distinct from one fought on the solidified lines of the old Western Front. Major-General Bernard Montgomery, commanding 3rd Infantry Division, complained for example that his divisional reconnaissance regiment, the 15th/19th Hussars (equipped with the Vickers light tanks), ‘attached more importance to billets and messes than to organized rehearsal for battle’. They were by no means alone in attracting the general’s displeasure, though they would undoubtedly have had the best officers’ mess.

In the regiments these defects were treatable by ruthless pruning and training. Higher up it was not so easy; and at the very top, next to impossible. The BEF’s commander-in-chief was General the Viscount Gort VC, DSO and two bars, MC.

178

There can be no arguing with such an unsurpassed record of valour, and yet Gort soon appeared out of his depth, derided as ‘the best platoon commander in France’. On 22 November Brooke wrote of him in his diary,

Gort is a queer mixture, perfectly charming, very definite personality, full of vitality, energy and joie de vivre, and gifted with great powers of leadership. But, he just fails to be able to see the big picture and is continually returning to those trivial details which counted a lot when commanding a battalion, but should not be the main concern of a Commander-in-Chief.

Perhaps the medals had dazzled during the inter-war years when, as in the late Victorian period, ‘regimental qualities’ had come to be seen as everything: no promotion board could have denied the next step on the ladder to those post-nominal letters. Or perhaps as a Grenadier and very much a ‘guardsman’s guardsman’ he had risen by that private Household elevator which had once been a feature of the army. Either way, it did not bode well.

There was a distant overture to the

Blitzkrieg

, however – in Norway. In early April, for a mix of political and military reasons including Russia’s invasion of Finland, the Nazi – Soviet non-aggression treaty, Swedish natural resources, the attraction of Norwegian bases for U-boats and the uncertainty of Anglo-French intentions, the Germans invaded Norway by invading Denmark en route, and also via Sweden which they traversed by the simple expedient of buying railway tickets. At Churchill’s urging (from the Admiralty, to which he had returned as first lord when war was declared) a hastily assembled landing force sailed for Norway in an attempt to forestall the seizing of the northerly ports. The force, also comprising French

Chasseurs d’Alpin

and Polish infantry, arrived too weak and too late, the Germans having already mounted a full-scale and highly effective invasion, although allied troops did help extricate the Norwegian royal family and much of the

country’s gold reserves (for which the Christmas tree in Trafalgar Square each year is a memorial gift of the Norwegian government). Perhaps the greatest consequence of the débâcle, for so the landings had been, was Chamberlain’s resignation and his replacement by Churchill at the very moment the Germans struck in the Low Countries – in the early hours of 10 May.

At a stroke the strategic situation now changed: Belgium was an ally once more. The flag dropped and the BEF sprinted across the Franco-Belgian border for the Dyle, and by the early evening its leading units had reached the river – including the 15th/19th Hussars who had presumably left behind their encumbering mess silver. They were not there long. The Belgian forts fell more quickly than in 1914, for the Germans did not tend to repeat obvious mistakes: they took Fort Eben Emael, for example, in a brilliant

coup de main

by parachute and glider troops. To make matters worse, on 14 May the Dutch, who did not escape invasion this time, capitulated, leaving the Dyle’s northern flank open. With the Belgian army rapidly disintegrating, and the French surprised – shocked – by armoured penetration of the Ardennes which threatened to outflank the Dyle in the south, the BEF began withdrawing on the evening of 16 May, re-establishing the defensive line west of Brussels along the River Escaut, with an intermediate line along the Dendre. It was pretty well a textbook operation, the divisional reconnaissance regiments covering the withdrawal much as they had done in 1809 at the beginning of Sir John Moore’s run for Corunna, although the 15th/19th Hussars (one of whose antecedent regiments had distinguished themselves covering Moore’s escape across the Esla) would pay dearly for the time they bought the infantry to get clear on the Belgian flank. Their Vickers light tanks were shot to pieces, and thereafter the regiment practically ceased to exist.

To the south the Germans, having slipped through the Ardennes, were making astonishing progress under General Heinz Guderian, the architect of the panzer forces. They had brushed the French aside at Sedan and crossed the Meuse with little difficulty, and by 19 May Guderian’s tanks – over 800 of them, faster than the British tanks yet with a better balance of protection and mobility and better armed, because they were intended for independent action, not as close support for the infantry – were at Abbeville near the mouth of the Somme.

That day, Gort signalled London that he had been ‘unable to verify that the French had enough reserves at their disposal south of the gap

to enable them to stage counter-attacks sufficiently strong to warrant expectation that the gap would be closed’. London replied that the BEF should fall back south-west along their lines of communication, but Gort, believing (rightly) that the French had little fight left in them and that such a move consequently risked encirclement, decided instead to withdraw northwards towards the Belgian coast – much to the anger of the new prime minister, though later, in his speech to the House of Commons after Dunkirk, Churchill would acknowledge the truth:

the German eruption swept like a sharp scythe around the right and rear of the Armies of the north. Eight or nine armoured divisions, each of about four hundred armoured vehicles of different kinds, but carefully assorted to be complementary and divisible into small self-contained units, cut off all communications between us and the main French Armies. It severed our own communications for food and ammunition, which ran first to Amiens and afterwards through Abbeville, and it shore its way up the coast to Boulogne and Calais, and almost to Dunkirk. Behind this armoured and mechanized onslaught came a number of German divisions in lorries, and behind them again there plodded comparatively slowly the dull brute mass of the ordinary German Army and German people, always so ready to be led to the trampling down in other lands of liberties and comforts which they have never known in their own.

The foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, who had been one of Chamberlain’s strongest supporters in the policy of appeasement but who had latterly embraced rearmament and taken a firm stand against Hitler and Mussolini, put it more prosaically in his diary on 25 May, but with the raw truth that had shaken Whitehall: ‘The mystery of what looks like the French failure is as great as ever. The one firm rock on which everyone was willing to build these last two years was the French army and the Germans walked through it like they did through the Poles.’