The Man Behind the Iron Mask (2 page)

Read The Man Behind the Iron Mask Online

Authors: John Noone

Apparently Louis XV had been informed by his predecessor in power, the Duc d'Orléans,

13

who had been Regent from the death of Louis XIV in 1715 until his own death in 1723. Unknown to Louis XV, however, the Regent had already betrayed the secret. His daughter, Charlotte de Valois, had persuaded him to disclose it to her. She had passed it on in a letter to her lover, Maréchal de Richelieu,

14

and he had left the letter among his private papers where it had been found by La Borde. The letter, as quoted by Grimm, began with a short message originally in code: âHere then is the famous story. I dragged the secret out. I had to pay a horrible price â¦' For Grimm's readers the price the young lady had to pay remained obscure, but the mystery of the Iron Mask was finally elucidated. The Regent had allowed his daughter to read a secret document, the contents of which she reproduced in her letter. This document was a death-bed confession made by an unnamed nobleman, who declared that he had witnessed the birth of the man who later became the Iron Mask, had been his tutor and had shared imprisonment with him until his death.

According to this nobleman's account â as retold by Charlotte de Valois, as reported by La Borde, as revealed by Grimm â the story began in 1638 when Anne of Austria, the wife of Louis XIII,

15

was pregnant. Two shepherds arrived in Paris, demanded an audience with the King, and warned him that his wife would give birth to twin boys, who would destroy the kingdom in their conflict over the throne. The King turned for advice to his Prime-Minister, Cardinal de Richelieu,

16

the great-uncle of Maréchal de Richelieu, who solved the immediate problem by having the two shepherds locked up in the asylum of Saint-Lazare. At midday on 9 September, the Queen gave birth to a son, Louis XIV, in the presence of all the witnesses normally demanded by law and protocol. But four hours later, while the King was taking his afternoon collation, the midwife, Dame Perronet, came to inform him that the Queen's labour pains had recommenced. The King hurried to her bedside, accompanied by the Chancellor, and, with no one else present except the midwife, the doctor and the nobleman responsible for the secret declaration, saw his wife give birth to a second son âmore handsome and vigorous than the first'. The King had everyone present sign a formal record of what had taken place and swear a solemn oath never to speak of it to anyone, not even to each other, and to reveal it only if the first-born twin should happen to die. The baby was then entrusted to Dame Perronet, who was ordered to pretend that it was the child of some lady at court.

When the child reached boyhood, responsibility for his upbringing was transferred to the nobleman, who took him to live in Dijon. The nobleman might have passed for the boy's father, but the extraordinary deference he always showed caused the young prince to ask questions, which were never answered satisfactorily. As the boy grew older, his curiosity increased, and by the time he was twenty-one his suspicions centred upon the fact that under no circumstances was he ever allowed to see a portrait of the King. Through all this time the nobleman had been in secret correspondence with the King, first with Louis XIII, who died when the boy was five, later with Louis XIV, who was crowned when the boy was sixteen, and also with the Queen, Anne of Austria, and Cardinal Mazarin, who was the successor of Cardinal de Richelieu. Somehow the young man contrived to find or intercept one of these letters and at the same time to persuade a chambermaid, who had become his sweetheart, to procure for him a portrait of Louis XIV. Armed thus with proof that he was the identical twin-brother of the King, he confronted his tutor and informed him that he was leaving at once for Saint-Jean-de-Luz in the South of France, where the court had gathered for the marriage of Louis XIV with Maria-Teresa of Spain. The nobleman had the young prince confined to the house while he informed the King of what had happened. As soon as Louis XIV got the news, he gave orders to have both the prince and the nobleman packed off to prison, first to the island of Sainte-Marguerite in the Bay of Cannes, and later to the Bastille.

Maréchal de Richelieu, among whose papers this supposed letter was found, died at the age of ninety-two, just one year before Grimm's remarkable disclosure was made. Aged nineteen at the time of Louis XIV's death, he had lived through the Regency, the reign of Louis XV and the first fourteen years of the reign of Louis XVI. Born to fortune and to favour, a soldier, diplomat and courtier of the highest rank, illiterate, arrogant, shallow, unscrupulous, dissolute and corrupt, he had made no discernable contribution to government, thought or art in all his long life of influence and power, but coddled by fortune he had outlived the witnesses of his mediocrity and become free in old age to feed his vanity with sensational accounts of his one time political acumen and mettlesome spirit, his military glamour and sexual prowess. The private papers he left behind were important not so much for any particular text they might have provided as for the pretext their mere existence offered. With Richelieu dead and revolution in the air, they could be used as the pretended source of endless bits of gossip or invention about the secrets and scandals of the old regime. The old man's image lent credibility to the pretence, and people believed it simply because they wanted to believe. When the first volumes of his pretended

Mémoires

appeared in 1790, they sold like hot cakes.

The man responsible for this publication was a defrocked priest by the name of Jean-Louis Soulavie, who claimed that Richelieu in the last years of his life had given him access to all his papers, along with the help of the private secretary whose job it had been for twenty-five years to classify them. In fact Soulavie felt as little concern for French history as he did for the Roman Church. The public was eager for sensational disclosures on the crimes and corruptions of the past, and in the pillage of the Revolution there was no shortage of material to satisfy them. Libraries and archives, looted from great houses, could be had by the cartload for next to nothing. Soulavie ran a writing factory where plundered material was sifted through by a team of scribes and hacks, copied, adapted, elaborated, transformed and finally compiled, under his direction, into something that would sell.

After Grimm's disclosure of the letter from the Regent's daughter found in Richelieu's papers, the readers of the

Mémoires

would expect to be treated to a section on the Iron Mask and they could not be disappointed. Grimm moreover had implied that the price paid by the lady to her father for the secret had been in some way shocking. Soulavie could not pass up such an opportunity, and had his Richelieu divulge all: âAt that time it was generally believed that the Regent knew the name of the Mask, the story of his life and the reason for his imprisonment, and so being more curious and daring than anybody else, I attempted, by means of my charming princess who curiosity was also aroused, to wrest the great secret from him. She always used to repulse the advances of the Duc d'Orleans and show a great aversion to him, but since he was nevertheless passionately in love with her and at the slightest hope of favour would grant her whatever she asked, I persuaded her to let him understand that he would be happy and satisfied if he allowed her to read the

Memoires of the Iron Mask

which were in his possession.'

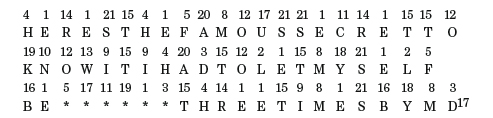

The plan worked: in return for making him âhappy and satisfied', the Regent gave his daughter the manuscript she wanted and the next day she sent it to Richelieu with a short message in code. To tease and tantalize his readers, Soulavie reproduced the note without deciphering it, and then seventy pages further on reproduced another note from the same lady in the same code, this time deciphered. Thus he allowed the reader the special thrill of turning back through the book and deciphering the first note for himself. In later editions, even this seventy-page gap was dispensed with so that the titillation could become immediate. With a little adaption to enable the system to work in translation, the note he printed read as follows:

The document referring to the Iron Mask, which was found among Richelieu's papers and published by Grimm, was a letter written by the Regent's daughter reporting information culled from a secret declaration. In Soulvaie's book the situation had improved with marvellous illogicality and devastating implausibility: the document, sent to Richelieu by the lady in question and found among his papers, was the secret declaration itself. It bore the following title:

Description of the birth and education of the unfortunate prince sequestrated by the Cardinals de Richelieu and Mazarin and confined by order of Louis XIV. (Written by the tutor of that prince on his death-bed.)

Soulavie reproduced it in its entirety, the same basic story as offered by Grimm, odd details omitted, changed or added, and all padded out to close on two thousand words.

Soulavie's version of the declaration differed from Grimm's only in the following particulars: a) the two shepherds were locked up by the Archbishop of Paris; b) âthe unfortunate prince' was born at half past eight in the evening while the King was at supper. The first chaplain and the Queen's confessor were also present; c) âthe unfortunate prince' cried at birth as if he knew even then the suffering he was to endure. He had birthmarks on his right thigh, his left elbow and the right hand side of his neck; d) it was the Cardinal de Richelieu who advised keeping the second twin out of the way but in reserve, though the Queen thought the danger of civil war greatly increased by the medical opinion that the last born of twins was the first conceived. The midwife was threatened with death if she ever betrayed the secret; e) the nobleman's house was in Burgundy, but not actually in Dijon; f) the letter stolen by âthe unfortunate prince' was one from Cardinal Mazarin, and it was a young governess of the house who gave âthe unfortunate prince' a portrait of the King; she did it because he was such an accomplished lover; g) the prisons in which âthe unfortunate prince' and the nobleman were confined were not named; h) the nobleman made his death-bed declaration to pacify his soul and to draw attention to the plight of âthe unfortunate prince', who at that time was still alive in prison.

As Soulavie himself remarked in a laboured display of objectivity, there was nothing in the declaration to prove that âthe unfortunate prince' was the Iron Mask, but since the stories of both, fragmentary and bewildering as they were when taken separately, appeared to complete and explain each other when put together, it was reasonable to suppose that they were one and the same. No one eager to accept the

Mémoires

as genuine was likely to refuse such a cautious supposition, and the myth of the Twin in the Iron Mask took its place in popular history, to be developed by romantic souls and exploited by political spirits in the century which followed.

In 1823, Emmanuel de Las Cases, who had been secretary to Napoleon during his exile on Saint Helena, published a journal of conversations with his master, in which for Friday 12 July 1816 he recorded a conversation on the subject of the Iron Mask. Much had been made of the idea, however fanciful, that the last-born of twins is the first conceived, and that therefore the Iron Mask, though younger than Louis XIV, was the rightful heir to the throne. Louis XIV was a usurper, and the legitimate possession of the crown had devolved upon his progeny only because the Iron Mask had died without children. In the popular myth developed around Napoleon was one ingenious fable which made him the descendant of the Iron Mask. According to this, the governor of the prison of Sainte-Marguerite allowed his daughter to visit the Iron Mask. The young couple fell in love and with the court's permission were married. Since the Iron Mask had no known name, the children of this union were given the name of their mother. That name was

de Bonpart

. The children were secretly moved to Corsica to be raised, and there the difference of language transformed their name from

Bonpart to Bonaparte.

Napoleon Bonaparte was of this family directly descended from the Iron Mask in an unbroken line of eldest sons, and that being so he was the legitimate heir to the French throne. In Napoleon's view the naivity and credulity of the general public was such that to establish such a story and find unscrupulous people in government to sanction it would not have been difficult. Someone else who took part in the conversation remarked that a genealogist had once seriously set about proving it to him, claiming that the record of a marriage between Mlle de Bonpart and the Iron Mask could be seen in the register of some parish church in Marseilles.

Meanwhile the Prince in the Iron Mask had inspired a pantomime, a tragedy, a four-volume novel and, in 1821, a dramatic narrative by Alfred de Vigny entitled

La Prison

. None of this work is remembered today except perhaps de Vigny's poem, three hundred lines of heavily sentimental excitement in verse-couplets, which tells the following story: An old priest clutching the viaticum is led, blindfolded and stumbling, through vast echoing galleries and narrow twisting passageways, to a dungeon dimly lit by torchlight where a mysterious prisoner lies dying. Soldiers remove the blindfold, and addressing the dying man as âprince', inform him that the priest has arrived. The reaction of the dying man is one of indifference at first, but the priest calls him âson' and at that he responds with bitterness. The priest exhorts him to confess his sins, sermonizing on penance and the sufferings of Christ, leans forward to peer into the shadows which hide the dying man's face, and is horrified at what he sees: