The Mapmaker's Wife (7 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Although the knights were fearless and brutal in battle, they were of the most delicate sort when it came to matters of love. Knights in a faraway land were constantly heartsick over beautiful maidens back home, who were locked away in castles. So great was their mutual passion that should a knight return and appear at his maiden’s window, her honor would be at great peril. How could she resist him? Yet the virtuous woman would find a way to remain in her chamber, offering her knight only a hand to kiss, for it was essential that she preserve her honor and remain a virgin until marriage. A similar chastity was not expected of the knight, however. He was quite adept at luring lower-class women into his bed, and in his travels abroad, he regularly took time out from his fighting to dally with the ladies. A knight, the writers made clear, was skilled at the art of seduction.

While the romances were fanciful in the extreme, they were presented to the public as historical novels, and readers often thought of them as true. As one sixteenth-century priest wrote, the books had to be factual,

“for our rulers would not commit so great a crime

as to allow falsehoods to be spread abroad.” Authors exploited this naiveté by calling their romances “chronicles,” often claiming that that they had simply rediscovered old handwritten texts recording past crusades.

Tirant lo Blanch

employed this device, as did the

Chronicle of Don Roderick

, which was sold as a “history” of the Moorish invasion of Spain.

This was the imaginative world that Spaniards inhabited in the early 1500s, and thus it was, their minds feverish with such fantasies, that they set off to conquer the New World.

T

HE

S

PANISH CONQUISTADORS

came from the same class of men that had waged the Reconquest. Many were poor, hailing from the harsh plains of Castile. In the first twenty-five years after Columbus’s 1492 voyage, they established control over Hispaniola and Cuba, explored most of the islands in the West Indies, and crossed over the Panama isthmus to the Pacific Ocean. And everywhere they went, they queried natives about where to find the mythical lands they had read about. Mexico was whispered to be such a place, and in 1518, those on an exploratory voyage from Cuba to Yucatán returned with thrilling news.

“We went along the coast where we found a beautiful tower on a point said to be inhabited by women who live without men,” reported a priest, Juan Diaz. “It is believed that they are a race of Amazons.”

This report stirred the governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez, to enter into a contract with Hernando Cortés for the conquest of Mexico. Velázquez warned Cortés to expect the fantastic,

“because it is said that there are people with large, broad ears and others with faces like dogs.” He also directed Cortés to find out “where and in what direction are the Amazons.”

Cortés sailed from Cuba with 600 men, sixteen horses, thirteen muskets, and one cannon—a small contingent to conquer an empire. After landing on the coast at a site he christened Villa Rica de Vera Cruz, Cortés took a page from the tales of knighthood and burned all his ships but one, which he offered to anyone who wanted

to turn back.

“If there be any so craven as to shrink from sharing the dangers of our glorious enterprise,” he told them, “let them go home, in God’s name. They can tell there how they deserted their commander and their comrades, and patient wait till we return loaded with spoils of the Aztecs.”

Cortés and his men were Amadís knights on the march. Their adventure soon unfolded like the plots in the novels they read. As they neared the central plateau of Mexico, Aztecs greeted them with glittering gifts from their ruler, Montezuma. The goods were meant as bribes—the Aztecs hoped that the Spaniards would take them and leave—but the treasures simply hastened Cortés’s march. He demanded to see Montezuma, and on November 8, 1519, he and his men were escorted along a great causeway into the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, which was built, in the manner of a fairy tale, upon islands in Lake Texcoco.

“We were amazed,” marveled Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier in Cortés’s army, in his

True History of the Conquest of New Spain

. “We said that it was like the enchanted things related in the

Book of Amadis

because of the huge towers, temples and buildings rising from the water and all of masonry. Some of the soldiers even asked whether the things we saw were not a dream.”

Within three years, the men of Castile had defeated the Aztecs, and while they were disappointed in the amount of gold and silver to be had, they took the place of the Aztecs as ruling overlords of Mexico. The legal method that the Spanish Crown had established for rewarding conquistadors was known as the

encomienda

system. A native village or group of villages would be “commended” to the care of an individual Spaniard, who was obligated to protect the inhabitants and bring in a priest to convert them to Catholicism. In return, the governing Spaniard, who was known as an

encomendero

, was authorized to collect a “tribute” from the Indians in the form of food, goods, clothing, and labor. Cortés became the master of 23,000 Indian families, while others in his army were awarded encomiendas of 2,000 households.

The conquest of Mexico inspired Spaniards to new heights of

fancy. While the Amazon women first spotted on the Yucatán coast had never materialized, their location was now better known. A tribe of women warriors, Cortés explained in a letter to King Charles V, was living on an island further west, where

“at given times men from the mainland visit them; if they conceive, they keep the female children to which they give birth, but the males they throw away.” There were also rumors circulating of an “otro Mexico” waiting to be discovered south of Panama, this one said to be even richer in gold and silver. The people there, the Spaniards believed,

“eat and drink out of gold vessels.”

In 1531, Francisco Pizarro, a soldier of fortune who was living as an encomendero in Panama, set out with 180 men and thirty-seven horses to conquer this empire to the south. He had the good fortune to arrive while the Incas were bogged down in a civil war. The Incas were a mountain people from the Cuzco region who had begun to conquer neighboring tribes in the middle of the fourteenth century. Over the next 150 years, they had extended their control over a territory that stretched more than 2,000 miles along the spine of the Andes, from Quito to the Maule River (in central Chile), with a total population of more than 10 million people. The Incas were skilled potters and weavers, and they had utilized advanced irrigation techniques to turn desert coastal areas into thriving agricultural regions. They had built more than 15,000 miles of roads. They also maintained warehouses of clothing, food, and weapons, and had a communication system, composed of relay runners, that could deliver a message from Cuzco to Quito, a distance of 1,230 miles, in just eight days. But around 1525, the reigning Inca, Huayna Capac, died of smallpox (a plague that had begun to creep south from Panama), and two of his sons, Atahualpa and Huáscar, immediately began a fratricidal battle.

Atahualpa controlled the northern half of the empire, and so it was he who heard, in late 1532, of Spaniards advancing inland toward his army of 40,000 headquartered outside the Andean village of Cajamarca, where he was enjoying the hot springs. The small group of intruders did not inspire fear in Atahualpa, and he,

like Montezuma, sent out emissaries bearing gifts—llamas, sheep, and woolens embroidered with gold and silver—and invited them to visit. Pizarro and his men peacefully entered Cajamarca on November 15, and the following day, Atahualpa was carried into the town square on a litter decorated with plumes of tropical birds and studded with plates of gold and silver. He was accompanied by 5,000 men and was expecting to dine with Pizarro, but instead, a Dominican priest, Vicente de Velvarde, stepped forward to read to him a formal document of conquest, known as the

Requierimiento

. The Spanish Crown, intent on believing that its conquest of the New World was a just and honorable enterprise, had drawn up this legal paper in 1513. All conquistadors were required to read it to natives before a notary and through an interpreter. It told of the history of the world starting with Adam and Eve, of man’s fall and his redemption by Jesus Christ, and the grant of dominion over the New World given to the kings of Castile by the pope. It concluded

by asking that aboriginal groups acknowledge their obligation to pay homage to the agents of the Spanish Crown, advising them that a gruesome fate would be theirs if they failed to submit. Friar Velvarde informed Atahualpa,

“We protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault.”

A sixteenth-century illustration of the conquest of Peru.

From

Historia General de las Indias y Nuevo Mundo

(1554). Biblioteca Universidad, Barcelona, Spain. Bridgeman Art Library

.

Once the Requierimiento had been read, the conquistadors were absolved by the church for any actions they subsequently took. Natives found the reading of this document utterly bizarre, and Atahualpa responded by throwing down the Bible he had been handed. Pizarro’s men took this as a signal to attack. They rushed into the plaza on horseback, shooting their muskets and hacking at panicked Incas with their swords. In the course of an hour, they killed more than 2,000 Incas without suffering a single death of their own. They also took Atahualpa prisoner. He agreed to pay Pizarro a ransom for his freedom, promising to fill a room twenty-two feet long and seventeen feet wide with gold piled nine feet high, and a smaller room twice over with silver. Over the next six months, his followers worked at doing just that, but before the rooms had been completely filled, the Spaniards grew restless and began melting the gold and silver treasures into ingots. Pizarro also reneged on his agreement and charged Atahualpa with a variety of crimes, including idolatry and adultery. After a short trial, he had Atahualpa strangled. A final tally of the spoils of conquest came to seven tons of twenty-two-carat gold and thirteen tons of pure silver. Even the lowliest infantryman accompanying Pizarro received forty-five pounds of gold and twice that weight in silver.

No Amadís author had ever dared to write such a script. The exploits of the literary knights paled beside those of Pizarro and his men at Cajamarca. Had not a handful of Castilians triumphed over an army of thousands without suffering a single death? Had not the square filled with the blood of the vanquished? Had not their own eyes seen a room filled with the most exquisite treasures of gold? Soon other such amazing events occurred. The Spanish conquered Cuzco on November 15, 1533, and there they found royal buildings covered with gold and virgins waiting in the temples. At

Potosí, high in the Andes, they discovered veins of silver so immense that it seemed the mountain itself must be made of this treasure.

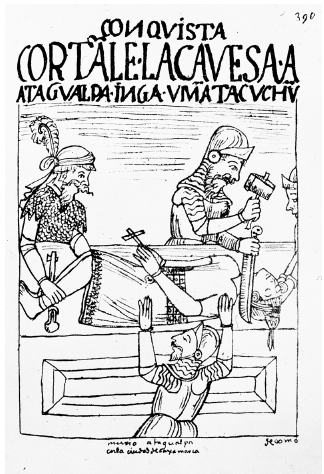

Execution of the Inca king Atahualpa.

By Felipe Huaman Poma de Ayala. Biblioteca del ICI, Madrid, Spain. Bridgeman Art Library

.

There was one final chapter in this knightly tale yet to come true: The discovery of the Amazons. Ever since the mythical warrior women had been sighted off the Yucatán coast, they had seemed to jump one step ahead of the advancing Spaniards. But much New World wilderness remained unexplored, and in 1541, Francisco’s brother Gonzalo Pizarro departed from Quito in search of El Dorado, a rumored kingdom of great riches east of the Andes. He and his troop of 200 men quickly became bogged down in the jungle, but a splinter group from his party, led by Francisco de Orellana, forged ahead and traveled down the length of a great river, all the way to the Atlantic. During this voyage—or so they reported—they came upon the fierce women the Spanish had been

seeking for so long. Friar Gaspar de Carvajal chronicled the astonishing sight:

These women are very white and tall, and they have long and braided hair wound about their heads; they are very robust and go about naked, their privy parts covered. With bows and arrows in hand, they do as much fighting as ten Indian men. Indeed, there was one woman among them who shot an arrow a span deep into one of the brigantines, and others less deep, so that our boats looked liked porcupines.