The Mapmaker's Wife (9 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Neither Bouguer nor Godin had publicly taken sides in the debate over the earth’s shape. Bouguer had tried to reconcile Newtonian and Cartesian views, while Godin had published a paper in 1733 describing how the distances between lines of latitude would vary depending on whether the earth was flattened or elongated at the poles. Either was possible from Godin’s point of view. But La Condamine had jumped into the fray on the side of the rebels. Maupertuis and Clairaut counted him as an ally, and Voltaire had written him a fan letter, hailing him as

“an apostle of Newton and Locke.” In 1733, La Condamine had floated the idea of mounting an expedition to the equator to solve the debate, but since he was a friend of the scorned Maupertuis and a junior member of the academy, Cassini and the other Cartesians had ignored him. It took someone of Louis Godin’s status to get the academy’s leaders behind the idea. Once they were, La Condamine, more than any

other member, lobbied to be named to the expedition. The academy, a colleague said,

“sensed that his zeal and courage would serve the enterprise well.”

Charles-Marie de La Condamine.

By Louis Carmontelle. Musée Conde, Chantilly, France. Lauros-Giraudon-Bridgeman Art Library

.

La Condamine, who had spent much of the previous sixteen months organizing the voyage, was the first to arrive in La Rochelle, having come in mid-April. The other seven members of the expedition were expected to assist the academicians, except perhaps for Joseph de Jussieu, who had his own scientific duties. Jussieu’s two brothers, Antoine and Bernard, were botanists and academy members, and they had requested that Joseph, a doctor at the medical school of Paris, be named the expedition’s botanist, charged with gathering plants and seeds from the New World. Joseph, however, had a fragile temperament, and everyone knew that he would have to be treated gently. His peers in Paris often spoke about his

“vivid imagination,” which was a polite way of saying that at times he was haunted by demons and prone to horrible bouts of melancholy.

Most of the others in the crew were professionals as well. The surgeon Jean Senièrgues would attend to the team’s medical needs, ready to bleed and purge at the first sign of sickness. Jean Verguin was a naval engineer and draftsman expected to draw maps. The watchmaker Hugo would be responsible for the care and maintenance of the scientific instruments, while Morainville, an engineer, would help build the observatories for their celestial measurements. The final two members of the expedition were younger men who would be general assistants: Couplet and Jean Godin des Odonais. Couplet was the nephew of the academy’s treasurer, Nicolas Couplet, and it was rumored that his uncle had twisted an arm or two to get him on the expedition. As for Jean Godin, he was Louis’s twenty-one-year-old cousin, and the minute he had heard about the expedition, he had hurried to Paris to volunteer.

The son of Amand Godin and Anne Fouquet, Jean was born on July 5, 1713, in Saint Amand, a village in the central region of France about 165 miles south of Paris. He was the seventh of eleven children, but only four of his siblings—two brothers and two sisters—survived

past infancy. Jean’s family was fairly prosperous. Amand was an attorney, and he also owned a property, Odonais, in the parish of Charenton, which provided Jean with the descriptive name—“des Odonais”—listed on the expedition’s travel documents. The countryside around Saint Amand was quite beautiful, the river Cher flowing through the fertile fields, and Jean would spend hours walking here, lost in his thoughts. He was

“born a traveler,” a relative later wrote. “As a child, he dreamed of far-off places.”

He would be paired with Couplet on the expedition. Their job would be to carry the survey chains and do the advance mapping that triangulation required. He and Couplet would be expected to travel ahead of the main group to identify the best geographical sites for establishing a triangulation point. Jean, as a nineteenth-century French historian noted, also planned to

“study at their source some of the lesser-known languages of the New World.” Upon his return to France, Jean hoped to publish a grammar on the New World idioms, establishing himself as an intellectual in his own right. He already felt the sting that comes from standing in the shadow of a famous relative, and—as his behavior on the expedition would later reveal—he wanted to be known as something more than just the cousin of a famous Parisian mathematician.

But on this day, those were half-formed ambitions. Jean had talked his way onto the voyage for the same reason that any young man would: He smelled adventure. He and the others would be the first group of foreigners to be allowed to travel to the interior of Peru, a colony that had stirred European curiosity for 200 years.

S

PAIN HAD SOUGHT

to keep the rest of Europe in the dark about its new lands almost from the moment of their discovery. By 1504, it had established a house of trade, the

Casa de Contratación

, to oversee all voyages to the New World. No one could ship goods or go there without the consent of the

Casa

. After Pizarro’s conquest of the Incas revealed the mineral riches of South America, Spain

formally decreed that no foreigner could enter its colonies. To put teeth into this law, Spain later declared that helping a foreigner enter Peru was a crime punishable by death.

As New World silver and gold flowed into Spain in the sixteenth century, France and the other European powers looked on with envy. What particularly galled them was that it was their uncouth neighbor to the south that had built this world empire.

“By the abundant treasure of that country (Peru),” Sir Walter Raleigh complained, “the Spanish King vexeth all the Princes of Europe, and is become in a few years from a poor King of Castile the greatest monarch of this part of the world.” French, English, and Dutch pirates regularly attacked Spanish ships in the colonial period, and occasionally they attacked Peruvian ports as well, which prompted Spain to further withdraw from the rest of Europe.

Ironically, it was a book by a Spanish priest, Bartolomé de Las Casas, that provided Europe with reason to season its envy with scorn. Until Las Casas published

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

in 1542, the story of Spain’s conquest had been written by chroniclers who had celebrated the conquistadors’ feats as heroic, surpassing in glory even those of the Castilian knights of old. Bernal Díaz del Castillo glorified Cortés’s triumph over the Aztecs in this way, and these early histories became known throughout Europe. But Las Casas, who went to the New World in 1502, saw things through a different prism. In his account, he likened the conquistadors to “Moorish barbarians” who, like

“ravening wolves among gentle lambs,” slaughtered Indians with abandon.

Hoping that his book would lead Spain to pass laws protecting the natives, Las Casas attacked all elements of the conquest. The encomienda system, he wrote, was

“a moral pestilence which daily consumes these people.” He said that the Requierimiento, the formal document of conquest, was so absurd that he did not know whether to laugh or cry. And in his book, he described one graphic episode after another of Indians being killed, raped, and enslaved. Francisco Pizarro and his men—according to the testimony of an

eyewitness who had told his story to Las Casas—were the worst brutes of all:

I testify that I saw with my own eyes Spaniards cutting off the hands, noses and ears of local people, both men and women, simply for the fun of it, and that this happened time and again in various places throughout the region. On several occasions I also saw them set dogs on the people, many being torn to pieces in this fashion, and they also burned down houses and even whole settlements, too numerous to count. It is also the case that they tore babes and sucklings from the mother’s breast and played games with them, seeing who could throw them the farthest.

While much of what Las Casas wrote was true, historians have noted that he also employed exaggerated rhetoric—such as the tale of baby tossing—to make his point. Las Casas hoped that his polemical book would stir reform in the colonies, but it served primarily to bring a flood of international hatred down upon his country.

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

was immediately translated into every major European language. The ghoulish engravings of a Protestant Flemish artist, Theodore de Bry, which accompanied the translations, deepened the image of Spanish cruelty. He drew scenes of pregnant Indian women being thrown into pits and impaled, of Indian babies being roasted alive, and of dogs tearing apart the severed limbs of those so slaughtered.

After the publication of Las Casas’s book, Spain redoubled its efforts to build a wall that would separate it and its colonies from Europe. In 1551, the Spanish Inquisition published its first Index of Forbidden Books, which was designed to keep reformist writings—like those of Las Casas—out of print. Anyone who dared to challenge biblical teachings or the Spanish monarchy risked being branded a heretic and burned at the stake. Seven years later, Spain banned all foreign books in Spanish translations. Violators of these laws could be put to death. In 1559, Spaniards studying in other European countries were ordered to come home, and those who

returned from the colonies hoping to tell of their experiences were forbidden to publish a word.

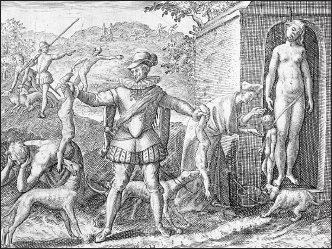

Theodore de Bry’s depiction of the Spanish hunting Indians with dogs.

By permission of the British Library

.

As a result of this censorship, the rest of Europe learned little about Peru or the rest of South America. Rumors, gossip, and the scattered writings of a handful of foreign traders were the primary sources of information, and these reports often encouraged the imagination to run wild.

One of the earliest travelogues was written by an Italian slave trader, Francesco Carletti. He returned from Peru in 1594 with tales of an amazing wilderness, reporting, for instance, that frogs and toads of “frightening size” were found in such quantity in Cartagena that people there were uncertain whether

“they rain[ed] down from the sky” or whether they were “born when the water falls and touches that arid land.” Vampire bats liked to feast on a person’s fingers and ears; chiggers bored into the feet and nibbled on the flesh until they grew fat; and in the forests, Carletti wrote, there were “mandril cats” so smart that, to cross a river, they linked

“themselves together by their tails” and swung from trees on one side of the river to the other.

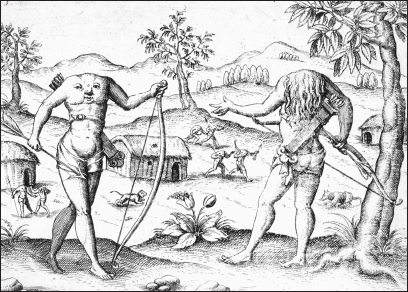

Levinus Hulsius’s depiction of Sir Walter Raleigh’s headless men in Guiana (1599).

By permission of the British Library

.

At this same time, the English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh returned with a report on the Guianas, where he had gone to search for El Dorado. This region, he said, was home to a fierce tribe of headless men, known as the Ewaiponoma, who had

“eyes in their shoulders and their mouths in the middle of their breasts, and a long train of hair growing between their shoulders.” Sir Walter also had met a man named Juan Martinez who claimed to have

lived

in El Dorado for seven months. This fabled empire, Raleigh wrote, was located around a salt lake 200 leagues (600 miles) in length and was graced by a city of stone, named Manoa, so grand in size that it

“far exceeds any of the world, at least so much of it as is known to the Spanish nation.”