The Marriage Book (41 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

Olivia Harrison (1948–) was the second wife of George Harrison, the Beatle known for his quiet demeanor, sharp cheekbones, sharp wit, and commitment to Eastern religion. In Martin Scorsese’s documentary about the late musician, the filmmaker interviewed Olivia, with whom George had been married—despite any number of twists and turns—for thirty years.

Sometimes people say, you know, “What’s the secret of a long marriage?”

It’s like, “You don’t get divorced.”

And I think, you know, you go through challenges in your marriage, and here’s what I found. First time we had a big hiccup in the road, I, you know, you go through things, and you go, “Wow, there is a reward at the end of it.” There’s this incredible reward. You love each other more. You learn something, you let go of something, you get—those hard edges get softened. You know, you’re that block of stone and life shapes you and takes away those hard edges.

QUEEN ELIZABETH AND PRINCE PHILIP, 1947 AND 2007

STEPHEN KING

“PROUST QUESTIONNAIRE,”

VANITY FAIR

, 2013

Stephen King (1947–) is the author of more than fifty novels and is considered the modern master of the horror genre. He married Tabitha Spruce in 1971.

Q: What do you consider your greatest achievement?

A: Staying married.

LEAP

JOHN HEYWOOD

PROVERB, 1546

At least one source, the online British

Phrase Finder

, claims that “look before you leap” originated not with horsemanship, but indeed with marriage—and this proverb.

And though they seeme wives for you never so fit, Yet let not harmfull haste so far out run your wit: But that ye harke to heare all the whole summe That may please or displease you in time to cumme.

Thus by these lessons ye may learne good cheape In wedding and all things to looke ere ye leap.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY RHYME

Some wed for gold and some for pleasure, And some wed only at their leisure, But if you wish to wait and weep, When e’er you wed,

Look well before you leap.

“THE SILENT PROPOSAL,” 1908

A British tradition holds that women may propose to men only on Leap Year.

W. H. AUDEN

“LEAP BEFORE YOU LOOK,” 1940

The editors of this volume are extremely partial to this poem, because we asked Lisa’s brother to read it at our wedding. Given the fact that we had met less than a year before, it seemed fitting for us. Most critics agree that W. H. Auden (1907–1973) wrote the poem not only as a general endorsement of risk taking but as a love poem to the American poet Chester Kallman.

Auden married Erika Mann, daughter of the German novelist Thomas Mann, so that she could attain a British passport and escape the Nazis. But it was his relationship with Kallman that he referred to as a marriage, and it lasted for several decades—though not always on sexual terms—until Auden’s death.

The sense of danger must not disappear: The way is certainly both short and steep, However gradual it looks from here;

Look if you like, but you will have to leap.

Tough-minded men get mushy in their sleep And break the by-laws any fool can keep; It is not the convention but the fear That has a tendency to disappear.

The worried efforts of the busy heap, The dirt, the imprecision, and the beer Produce a few smart wisecracks every year; Laugh if you can, but you will have to leap.

The clothes that are considered right to wear Will not be either sensible or cheap, So long as we consent to live like sheep And never mention those who disappear.

Much can be said for social savoir-faire, But to rejoice when no one else is there Is even harder than it is to weep;

No one is watching, but you have to leap.

A solitude ten thousand fathoms deep Sustains the bed on which we lie, my dear: Although I love you, you will have to leap; Our dream of safety has to disappear.

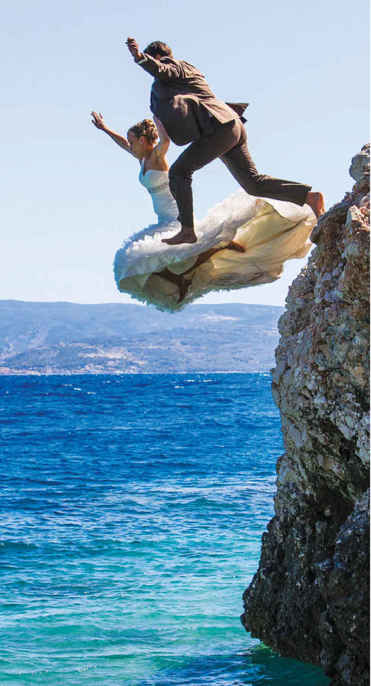

WEDDING IN CROATIA, 2012

The leap was by a just-married couple, the photographs by Zvonimir Barisin.

LEGALITIES

MESOPOTAMIAN MARRIAGE CONTRACT, 2200 BC

The bride, a slave, attained her freedom through this marriage; the groom attained a bride. This apparently accounted for the difference in penalties if either of them wanted out.

If Bashtum to Rimum, her husband, shall say, “You are not my husband,” they shall strangle her and cast her into the river. If Rimum to Bashtum, his wife, shall say, “You are not my wife,” he shall pay ten shekels of money as her alimony.

EGYPTIAN MARRIAGE CONTRACT, 200 BC

Among the many discoveries made in Luxor in the early part of the twentieth century was this marriage contract. It was written in demotic, the Egyptian vernacular of that period, and inscribed on an

ostracon

, or pottery shard. Historians suggest that the idea of a trial marriage may have been rooted in the importance of children in Egyptian life and thus of a wife’s early pregnancy.

The

stater

was an early Greek coin. The word

ostracon

derived from the practice Athenians had of writing the names of outcast citizens on shards of pottery—hence the word

ostracism

.

I take thee, Taminis, daughter of Pamonthis, into my house to be my lawful wife for the term of five months. Accordingly I deposit for you in the Temple of Hathor the sum of four silver stater, which will be forfeited to you if I dismiss you before the conclusion of the five months, and besides this my banker shall do something for you. But if you leave me on your own account before the end of the five months, the above sum which I have deposited shall be refunded to me.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

LETTER TO LEOPOLD MOZART, 1781

Rumors that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) had been carrying on an inappropriate relationship with Constanze Weber, at whose family’s house he had been boarding, were circulating throughout Vienna and Salzburg in the autumn and winter of 1781. In this unctuous letter to his ever-critical father, Mozart explained that the rumors were the reason that Constanze’s guardian had insisted Mozart sign what was in effect a prenuptial agreement.

Mozart and Constanze (he alternated between spelling her name with a

C

and a

K

) were married the following year and remained so until his death.

But let me talk now about the Marriage contract, or rather the written assurances of my honorable intentions concerning the girl; you do know, don’t you, that they have a guardian because—unfortunately for the family and also for me and my Konstanze—the father is no longer living—and this guardian, who doesn’t even know me, must have gotten an earful about me by such servile and loudmouthed gentlemen as Herr Winter:—that one must beware of me—that I had no secure income; that I was too intimate with her—that I might jilt her—and that the girl would be done for in the end, etc.; all this stuff wafted like a bad odor into the guardian’s nose—because Constanze’s mother, who knows me and my honest behavior, allowed all this to be said without saying anything that would put it right.—Yet, my entire association with them consisted in my—living there—and afterward in my visiting there every day.—No one ever saw me with her outside the house.—But this guardian filled the mother’s ears with stories about me for so long until she finally told me about it and asked that I have a talk with him myself, because he was supposed to come by the house in a few days.—He came—I spoke with him—the result was (because I did not explain things as clearly as he had wished) that he told the mother to forbid all association between me and her daughter until I had settled the matter in writing.—The mother told him: his entire association with her consists in coming to my house and—I can’t forbid him my house—he is too good a friend for that—a friend to whom I am obliged in many ways.—I am satisfied and I trust him—you must work out an agreement with him yourself.—So then he forbade me to have anything to do with the girl until I acknowledged my relationship in writing. So what other recourse did I have?—to give him a written contract or—never to see the girl again—but if you love honorably and truly, can you forsake the one you love?—could not the mother, could not my beloved herself, come up with ugliest interpretation of my conduct?—Such was my situation! So, I drew up a document in which I stated

that I obligated myself to marry Mad.elle Constance Weber within the time of 3 years; if it should prove impossible for me to do so owing to a change of mind, she would be entitled to receive from me 300 gulden a year.

—Nothing in the world was easier for me to write—because I knew I would never have to pay these 300 gulden—for I shall never forsake her—and even if I should be so unfortunate as to undergo a change of mind—I should be glad that I can liberate myself for a mere 300 gulden—and Konstanze, as I know her, would be too proud to let herself be bought off.— But what did this heavenly girl do as soon as her guardian had left?—She demanded that her mother give her the document—then said to me—

dear Mozart! I don’t need any written assurances from you; I believe what you say

; and she tore up the writ.—This gesture endeared my Konstanze to me even more.—and because she tore up the contract and the guardian gave his Parole d’honneur to keep this matter to himself, my mind, dearest father, was somewhat put at ease when I thought about you.—For I am not worried about obtaining your consent to get married when the time comes, for the only thing the girl lacks is money—and I know how reasonable you are in such matters. So will you forgive me?—I do hope so!—in fact, I don’t doubt it at all.