The Mistletoe Bride and Other Haunting Tales (16 page)

Read The Mistletoe Bride and Other Haunting Tales Online

Authors: Kate Mosse

Tags: #Anthology, #Short Story, #Ghost

Allemonde, a legendary land

The Past

Author’s Note

This story was written in May 2008 for a 75th-anniversary celebration for Glyndebourne Opera House in Sussex,

Midsummer Nights

. Each author in the collection was invited to choose one – significant – opera as their inspiration and I chose

Pelléas et Mélisande

by Claude Debussy. Debussy is an off-stage character in the second of my Languedoc Trilogy,

Sepulchre

, which is partly set during the 1890s, so I had been listening to a great deal of French impressionist music and reading symbolist poetry, plays and novels to all the better immerse myself in the world of

fin-de-siècle

Paris.

Pelléas et Mélisande

, the only opera Debussy wrote, premiered at the Opéra-Comique in Paris in April 1902. Adapted from Maeterlinck’s symbolist play of the same name, it had mixed reviews at the time, though quickly became seen as marking a turning point in the development of opera from its nineteenth-century traditions to a musical form lighter on its feet.

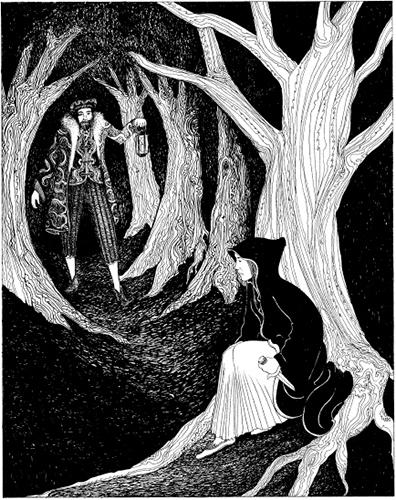

For readers not familiar with Maeterlinck’s tragic tale or Debussy’s interpretation, here are the bare bones of the story. A man quick to anger, violent and jealous, Prince Golaud comes across a young woman, Mélisande, wandering lost in a forest. Timid, fearful, traumatised, she does not know where she has come from – though she remembers a sea journey – and has no idea why she finds herself in this strange, dark kingdom. Golaud marries her and takes her home to the court of his grandfather, the old blind King Arkel, where Golaud’s mother Geneviève and his young son from an earlier marriage, Yniold, live. Golaud’s half-brother, Pelléas, is also resident at the castle, though he is seeking permission from Arkel to leave.

This being opera, Pelléas and Mélisande fall in love. She is expecting Golaud’s child, but she lives in fear of his violent temper and his jealousy – in Act I, when she loses her gold wedding ring, Golaud forces her to go to find it, despite her terror of the dark – so she looks, in part, to Pelléas for protection. Suspicious, vengeful, Golaud becomes obsessed with finding out the ‘truth’ – ‘

la verité

’ – of the relationship between his half-brother and his wife, and he forces his son, Yniold, to spy on the pair. When Golaud sees them taking their leave of one another by the fountain in the grounds – they understand their love affair cannot be – he stabs Pelléas and pursues the grieving Mélisande. The closing scene of Act V sees Mélisande going into labour prematurely and dying as her daughter is born, without ever holding her. Even then, rather than seeking forgiveness or attempting to atone for his actions, Golaud still demands ‘the truth’. The whispering final lines hint that the same fatalistic pattern of misery and twisted love is destined to continue down the generations.

From there, I imagined the childhood of this unwanted, unmothered child, Mélisande’s daughter – I gave her the name Miette, ‘little one’ – and what might it have been like to grow up in the sombre halls of the castle, in the shadow of murder. How Miette might have felt hearing rumours about her mother’s death and her uncle’s murder, her suspicions of what might have happened to Yniold’s mother, Golaud’s first wife. Seeing her father not brought to account for his deeds, because of his high birth, yet nonetheless a man haunted by the past and making an annual pilgrimage to the scene of his crime. With such a background, it seemed natural that Miette, purposeful and determined, would grow up to want to avenge her mother.

In the writing, I wanted to mirror the dreamy, otherworld quality of Debussy’s score, the indeterminate setting, the blurring of past and present and future, the sense that nothing was certain, nothing was quite as it seemed. Such is the nature of mythologies and legend, both symbolic and real, not fixed in place or time, but rooted instead in impression, in emotion, in atmosphere. My story is set, however, on the occasion of Miette’s eighteenth birthday . . .

The ideal would be two associated dreams.

No time, no place.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY,

writing about

Pelléas et Mélisande

in 1890

White is the colour of remembrance. The hoar frost on the blades of grass that cling to the castle walls, the hollow between the ribs and the heart. A shroud, a winding sheet, a ghost.

Absence.

The trees are silhouettes, mute sentinels, slipping from green to grey to black in the twilight. The forest holds its secrets.

Mélisande’s daughter, Miette, presses herself deeper into the green shadows of the wood. She can see glimpses of

La Fontaine des Aveugles

through the twisted undergrowth and juniper bushes. It is late in the day and already the light has fled the sombre alleyways of the park and the gloomy tracks that cross the forest like veins on an old man’s hands.

White is the colour of grief.

This is the anniversary of her mother’s death when, according to the mythology of the land, the paths between one world and the next are said to be open. It is not a night to be abroad. It is also Miette’s birthday, although this has passed without celebration or comment these past eighteen years. The date has never been marked by feasts or fanfares or ribbons.

The story of Mélisande – forbidden love, tragic beauty, a heroine dead before her time – this is the architecture of legend, of fairytale, of poetry and ballad. How could the existence of an unwanted, though resilient, daughter possibly compare? A watchful daughter biding her time.

Miette presses her hand against the silk of her robe, feeling the reassuring crackle of the paper. It is her testament, her confession, an explanation of the act she intends to carry out today. She knows her father, Golaud, has murdered once, if not twice – and holds him responsible for her mother’s death – but yet he has kept his liberty. He has never been called to account. This is not how it will be for her. Although she is the great-grand-daughter of old King Arkel, she is a girl not a boy. She is considered of no account. Besides, Miette wants to explain her deeds, make herself understood. In this, as in so many other ways, she is not her mother’s daughter. Everything about Mélisande’s life – her delicate spirit, her fragile history – remains as indistinct as a reflection moving upon the surface of the water. Where had she come from before Golaud found her and brought her to Allemonde? What early grief had cracked her spirit? What were her thoughts as her wedding ring fell, twisting, down into the well, knowing the loss of it would matter so much? How tripped her heart when she looked at Pelléas and saw her love reflected in his eyes? Did she catch her breath? Did he?

Did she know, even then, that her story would be denied a happy ending?

Miette grew up in the shadow of these stories, now grown stale and battered around the edges. Whisperings about her father, Golaud, and his violent jealousy. Of her mother, Mélisande, and her gentleness. Of how her long hair tumbled down from the window like a skein of silk. Of her uncle, Pelléas, and his folly. Of the others who stood by and did nothing.

Green is the colour of history.

Not the white and black of words on a page or notes on a stave. Not the frozen grey of tombstones and chapels. It is green that is the colour of time passing. Olive moss, sable in places, covering the crow’s feet cracks in the wall. Emerald weeds that spring up on a path long unused. The lichen covering, year by timeless year, the inscription on the headstone, the letters, the remembered name.

At her nurse’s knee, Miette learned the history of Pelléas and Mélisande. A history, a tale, is no substitute for a mother, but it gives a purpose to the suffering. Their story is the legend of Allemonde, a tale perfect in its construction –

un amour défendu

, a sword raised in anger. Always the balance of the light with the dark, the ocean with the confines of the forest, the castle and the tower. The colours, the texture of the story, Miette pieced together from what was left unsaid between her half-brother, Yniold, and her father.

The truth she learned from her grandmother, Geneviève. Of how men use women ill. How money buys safety, if not peace. Of how the faults of one generation are passed down, silent and sly, to the next. Of how the truth is always shabby, always mundane when set next to the stuff of legend.

In her green hiding place in the forest, Miette sighs, caught between boredom and terror. Her confession and weapon lie concealed beneath her cloak. She is eighteen today. She will act, today.

Il est presque l’heure

.

Her father’s custom on this day are well known. From the white-haired beggars at the gate to the servants that walk the sombre corridors of the castle, all of Allemonde knows how Golaud, the widower – some say, the murderer of wives – makes his annual pilgrimage to

La Fontaine des Aveugles

on the anniversary of Mélisande’s death, though Miette’s birthday is not remembered. Golaud comes to mourn, some say, or to pray. To weep, to pick over the bones of his life. No one knows if it is remorse or grief that guides his steps. He has never shared that chapter of his story and Miette never asked for fear it would strip her purpose from her.

In the distance, the chiming of the bell. The sheep in the fields begin their twilight chorus, the mournful chorus for the passing of the day. Out at sea, the sun is sinking slowly down beyond the horizon, as every day for centuries. And in the palace, the slow and steady business of lighting the candles will now begin. The yellow flames dancing up along the stone walls and grey corridors.

The legend of Mélisande holds that she dreaded the dusk. Miette does not know if this is true. They say that Mélisande feared the night. The ringing of the Angelus bell, the closing of the gates in a rattle of wood and metal and chain – all this made her think of the grave where the worms and spiders dwelt. Mélisande turned to the west, or so Miette’s nurse told her, to the setting sun and the shore, as if looking for that first ship, long departed, which had brought her as a child-bride to Allemonde from who knows where. As if hearing, still, the cries of the sailors and the gulls. An echo of a memory of happier times? Miette glances down and sees the tips of her satin slippers are stained with the first touches of the evening dew brushing the grass.

She shivers and pulls her cloak tight around her with her slim, strong arms. Deep in the folds of cloth, she presses the tip of the knife against her thumb, softly at first, then harder until her skin is pierced, then withdraws her hand. A single, red pearl of blood hangs suspended, like a jewel in the twilight.

There are beads of perspiration at the nape of her neck now beneath the canopy of her hair, worn long in remembrance of her mother. The mother who never held her. Although an inconvenience, the braids are a symbol of the connection between them. Brushed, plaited, smoothed. Though everyone tells Miette she is more her father’s daughter. She is quick to temper, black moods threatening, easily frustrated.