The Mistletoe Bride and Other Haunting Tales (17 page)

Read The Mistletoe Bride and Other Haunting Tales Online

Authors: Kate Mosse

Tags: #Anthology, #Short Story, #Ghost

Vengeful.

Beneath the trees, Miette shifts slightly from foot to foot, feeling the cold seeping up from the earth and the roots into her young bones. She does not know how long she has been waiting, entombed in the green embrace of the wood. Long enough for dusk to fall, it seems both an eternity and a moment. Eighteen years, in truth, and although she has been biding her time, all these minutes and hours and weeks, Miette feels panic rising in her throat, nausea, sour and bitter. She wills herself not to lose her nerve. Not now, not at the moment she has been planning for so long. Waiting for.

Pas maintenant.

Red is the colour of dying. What else could it be?

The violent rays of the setting sun through glass, flooding the chamber crimson. The petals pulled from a rose, strewn on the cobbled stones of a garden no longer tended. The colour of the damaged struggling heart. Blood dripping through the fingers.

To steady her nerves, Miette sends her thoughts flying back to the castle. She remembers herself at seven or eight years old, carried on Yniold’s shoulders. Laughing, sometimes. Content, sometimes. But, quick, the darker memories come. Her past unfolds in her memory like the decaying slats of a paper fan. Older, eleven or twelve, tiptoeing alone down dusty corridors. Or, later still, hidden beneath the covers in her cold chamber, hands over her ears, trying not to hear her father shouting or Yniold weeping. Fear or humiliation, the sound was the same.

A bird flies up out of the trees, the abrupt beating of its wings upon the air mirroring the rhythms of her own anxious pulse. Miette narrows her eyes, sharpens her ears. In the distance, now, she can hear something. The subtle snap of twigs on the path, the rattling of rabbits seeking cover in the undergrowth, the shifting of the atmosphere. Someone is coming.

Him? The man who is her father, though she feels no love or duty to him? Is it he?

Miette stiffens. She has imagined this scene so many times. The single strike of the knife, an act of revenge. An eye for an eye, a blade for a blade. She has imagined how Golaud, wounded, would reach out his hands to her, as once Mélisande had reached for the baby daughter she could not hold. How he would ask her forgiveness.

And, even now, she could give it. Absolve him for his sins. Absolve herself for what she has done.

‘

Je te pardonne. Je te pardonne tout.

’

That hour has not yet come. Miette waits, holding her breath, wishing the deed could be over. Or need not to be done at all.

The light from a lantern, jagged and uneven, is getting closer. Miette can distinguish the sound of breathing above the twilight sighings and whisperings and chitterings of the forest. The rattle of an old man’s chest as Golaud walks out of the darkness, out of the cover of the trees and into the glade, following the well-worn path to

La Fontaine des Aveugles

– the Fountain of the Blind Men – to the place where Pelléas fell.

He moves slowly, pain in every step. Miette watches him and feels nothing. His body is failing him. He is old. His wounds, from war or the hunt, sing loud in the damp evening air. The scars, beneath the velvet of his robes, remind of hunting accidents and the memory of metal and spear. The crumbling of sinew and bone, eating him away from the inside out, grief or regret or anger? For eighteen years she has asked herself the same question, and received no answer. But she does not pity him. She cannot. She thinks only that he must be called to account. In Yniold’s absence, his lack of will, it falls to her.

A daughter to avenge a mother, a less familiar story.

Golaud places the lantern uncertainly on the edge of the well. Miette waits. It is not yet her turn to step upon the stage. Her father is muttering, talking, but so softly that she cannot distinguish one word from the next. She moves a little closer, picks out the words.

‘

La vérité. La vérité

.’

Over and over, like a chorus refrain, the syllables bleeding one into the other and back again. Demanding the truth. The words he said to his Mélisande as she lay dying.

Tell me the truth.

Golaud leans forward, two twisted hands in the yellow halo of light on the grey stone of the well. Miette steps forward, in silence and without drama. For if she is to rewrite this story, it cannot be told in noise and emotion, but rather enacted with cold purpose. It is a practical ending, not a theatrical one.

One step forward, then two.

Un, deux, trois loup.

Coming to get you, Mr Wolf, ready or not. A game of grandmother’s footsteps played by two lonely children, she and Yniold, in a desolate palace long ago.

With a third silent step, she is on him.

Now, at last, she is ready to join herself to him. A murderer for a father, a murderer for a daughter.

As Golaud stoops forward to gaze into the blind eye of the water, Miette has the advantage of height. Thinking of Mélisande and her Pelléas, of Yniold’s mother too – dead before her time – Miette lifts the knife and, with the strength of both hands and the weight of her body, she brings the blade down between her father’s shoulders.

He cries out, once, like an animal caught fast in the metal jaws of a trap, then nothing. She has heard it said that the soul takes flight alone and in silence. She does not know if this is true, only that he does not speak or cry out again.

Miette relinquishes her hold on the hilt and steps back, half stumbling on the hem of her cloak beneath her heel, sodden with dew. She, too, is silent. There is nothing to say, though she wills him to turn, wishing her act of vengeance to be understood. At the same time, she does not want to see the life leaving him or her own image reflected in his dying eyes.

Golaud falls forward, as once Pelléas had fallen. His hands slip from the wall, empty fingers scratching down the stone surface of the well, down to the ground. No crash of cymbals to mark the moment of death, no crescendo, merely justice done.

Then, a nightjar calls, a spur to action. Taking the letter from her pocket, Miette places it upon her father’s body. The testimony of Mélisande’s daughter, eighteen years in the telling. A confession of why and how she killed her father.

‘

La vérité

,’ she whispers.

This is the truth. Set it down, set it down.

The truth is that stories can be rewritten. Acts of love and death.

Miette stretches to take Golaud’s lantern from the rim of the well, taking care not to touch him, then turns to walk back through the forest. How easy, it seems, to kill a man. So easy to separate the spirit from the skin and bone?

In the distance, the bell strikes another hour. It marks the end of one history and the beginning of another.

Gold is the colour of loyalty. Of a duty fulfilled.

The Fishbourne Marshes, Sussex

Winter 1955

When latest autumn spreads her evening veil,

And the grey mists from these dim waves arise,

I love to listen to the hollow sighs

Thro’ the half leafless wood that breathes the gale.

For at such hours the shadowy phantom pale,

Oft seems to fleet before the poet’s eyes;

Strange sounds are heard, and mournful melodies

As of night wanderers who their woes bewail!

from Sonnet XXXII, ‘To Melancholy’

CHARLOTTE TURNER SMITH

I first saw her on a Thursday afternoon. She was ahead of me on the path out on the marshes, walking fast as if to keep an appointment. Her hands were dug deep in her pockets and her shoulders hunched. A blue belted jacket and pleated skirt, white shirt just showing above the collar and shoes suitable for pavements not mud. Seamed stockings. Later, I realised why she looked familiar and why the look of her struck a false note.

But not then. Not that first time.

That Thursday, I stopped, puzzled I’d not noticed her before. The path, at this point, was narrow and accessed only from Mill Lane, and though I usually walked down to the estuary in the afternoon, when I could get away, it wasn’t a popular spot. Although the lights of the lending library were visible on the far side of the field, most local people considered this area west of the Mill Pond too deserted, too overgrown and that November it had rained and rained.

She was too far ahead for me to make out her features and, besides, she didn’t turn round. But her brown hair, visible beneath the rim of her cap, looked salon curled and from the way she moved, I thought she was about my age. That, too, stuck in my mind. Those who did come out this way were mostly old men with time on their hands, or farm workers taking a short cut across the fields to the big houses up along. Not girls in their twenties.

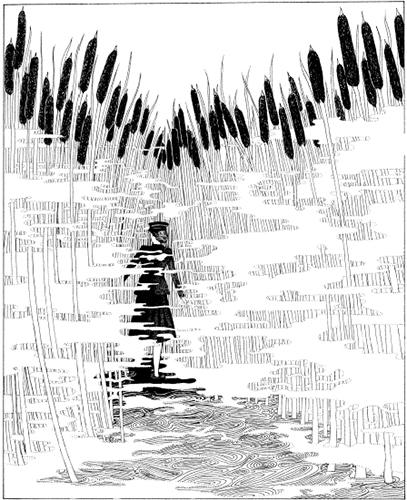

I followed her along the path, in that awkward proximity of strangers. I picked up my pace, feeling my gumboots slip on the mud. Was I hoping to catch up with her? I’m not sure of anything except that she stayed precisely the same distance ahead. But when I rounded the bend in the path, she’d vanished. I stopped again, trying to work out where she’d gone. There was a trail that cut down through the reed mace to the water’s edge, white stones marking a route over the mud flats at low tide. The sea was right up, though, and not even a local would reckon you could get across. I looked behind me, in case she’d doubled back, but there was no sign of her.

What else? An odd smell, like rotten eggs, like seaweed on the shore in summer.

Thursday, 24th November, 1955, an afternoon like any other. My routine, in those days, rarely altered. On Monday and Thursday afternoons, I helped out in the library as a volunteer. It was a debt, of sorts. When I was growing up in Fishbourne, the library was the only place I felt was mine. We had no books to speak of at home and, besides, my stepfather didn’t think girls should waste time reading. Didn’t think they were good for anything but cooking and fetching and carrying. In the library I was let alone. No one shouted at me, nobody took the mickey. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, I travelled the world in the company of Agatha Christie and Eleanor Burford and Rider Haggard, dreaming of what I’d be when I grew up. Nothing came of any of it – Harry’s trouble with the police, then the war put paid to dreams of leaving – I retained an affection for the place. So when I found myself back in Fishbourne fifteen years later, the library seemed the obvious place to offer my services. And even now, when I stepped through the big oak doors, and breathed in the familiar perfume of dust and polish, life didn’t seem so bad for an hour or two.

That Thursday the library was closed. A burst pipe had flooded Natural Sciences and we had all been sent home. So after I’d cleared the table and the dishes were stacked and drying on the draining board, I asked our neighbour, Mrs Sadler – who came in to keep an eye on my stepfather when I was at work – if she wouldn’t mind staying on for a while anyway, so I could slip off.

I went out by the side door, turning the handle slowly so as not to disturb him. Old habits die hard. Over the main road, quiet in the drowsy part of the afternoon, down Mill Lane and out onto the estuary, where the salt marshes lay spread out like a battered old map. When we were children, my older brother forced me to climb down the bank into the muddy creek. I was scared of the filthy, tidal water, but I was more frightened of Harry’s temper, so always did what he told me. It was different when I managed to get out on my own. Then, I could kick my heels. Bright days when the sun bathed the Downs in the distance in a chill yellow light. Stormy days when black clouds scudded along the horizon, the smell of bonfires heavy in the air. The soft days of spring, when pink ragged robin and southern marsh orchids pricked the green, or the white flowers of lady’s smock, identified from the Collins Guide borrowed from the Natural History section in the pocket of my regulation school coat.

We left Fishbourne when I was twelve, too young to understand the whispers or the way neighbours fell silent when Harry stepped into the Woolpack Inn. I knew there was talk – about him, and my stepfather too – but my mother never explained and I was too timid a girl to ask. Then Harry signed up – moment he could, couldn’t wait to get away – and went to war. Never came back. When we came back to Fishbourne, I realised there had been rumours about the pair of them, Harry and my stepfather, even before it happened. I never wanted to come back to this corner of Sussex – it rubbed it in how little I’d made of my life, to end up back where I’d started and been so unhappy – but my stepfather was insistent and my opinion wasn’t taken into account. I understand now that, as his mind started to unravel, something drew him back.