The Modern Middle East (14 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

In Saudi Arabia at the start of the 1920s, state building was at a far more embryonic stage than in Turkey or in Iran. In fact, while Abdel Aziz ibn Saud built a “state,” he did not start its construction until

after

he had unified Arabia in the early 1930s, and even then he built only a skeletal one—a more urban and urbane version of what he had earlier ruled as a tribal warrior. What occurred in the Arabian deserts in the 1910s and 1920s was, more accurately, a process of “nation building,” in which a series of conquests and alliances brought disparate tribes under one, increasingly national umbrella. Only after a measure of national cohesion had been accomplished could the construction of a state apparatus be started, a task that the first two Saudi monarchs undertook only haltingly.

Nevertheless, all three political systems discussed here had an important feature in common, and still do: they were created, maintained, and nurtured by one individual, someone who was not just a founding father but a personality larger than life, the embodiment of everything political. From the very beginning, each of these systems, like many others in the Middle East before and after them, was a personal creation, and, more importantly, a personal possession. Individuals came to personify systems; politics was relegated to the domain of personal relations; and institutions assumed only a secondary importance, to be bent and shaped in whatever way the

nation’s father willed. Such was Middle Eastern politics from the 1920s to the 1940s, and its essence, as will be seen later, would change little for more than a half century afterward.

Just as the Great War fundamentally altered the political geography of the Middle East, so did the Second World War. Beginning in the second half of the 1940s, mandatory protectorates were given their formal independence, and a new country, the state of Israel, was born. Thus ensued one of the most traumatic phases in the life of the contemporary Middle East. The next chapter turns to that era.

3

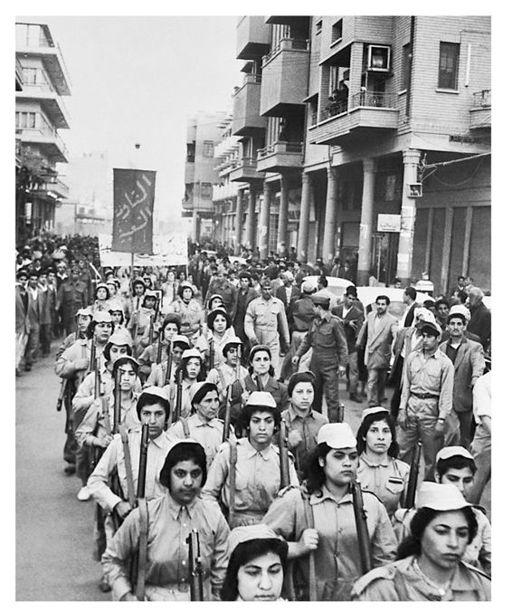

The Age of Nationalism

In the Middle East, as elsewhere, nationalism has been a powerful force shaping the destiny and character of peoples and countries. Although most conventional accounts of nationalism in the Middle East trace its genesis back to the mid-nineteenth century, it was in the 1940s and the 1950s that nationalism became what it has been ever since, one of the most dominant forces—if not

the

most dominant force—in the region’s politics.

Enormous scholarly energy has been spent on defining nationalism and exploring the causes of its birth, and what follows here is of necessity brief and general.

1

For the purposes of this chapter, I take

nationalism

to mean simply attachment on a national scale to a piece of territory, reinforced by common bonds of identity such as shared symbols, historical experiences, language, folklore, and whatever else creates a sense of commonality. At times, these common bonds include religion. This conception of nationalism has two important elements. First, there must be a definite territorial frame of reference, a piece of geography toward which a sense of attachment and loyalty is directed. This may be a result of economic ties to the land, its products having served as a source of livelihood for successive generations, or it may be more immediate and primordial, resulting from the need for shelter, personal security, and the sanctity of one’s private household. Second, this territorial attachment needs to become national in scope, a transformation often achieved only through active ideological, political, and at times even military agitation on the part of political leaders and states.

The first element of nationalism, identification with a piece of territory for economic and/or personal reasons has been a feature of human societies from the beginning of settled life, when the ability to own or at least to live and work on land became a central feature of daily living. By itself, however,

this sense of attachment to land, rooted in necessity, is parochial and localized, limited in scope to units that can conceivably be as few as one or two families. What is essential is for such an attachment to become national in scope, embodying individuals not only in isolated pieces of territory but in an organically and emotionally linked territorial entity that contains various towns and cities. The organic and emotional links are reinforced by shared symbols and experiences and by other similar bonds of commonality. In other words, a

nation

needs to have been formed, or to at least be in the process of formation, for attachment to territory to be enhanced in scope and transformed into nationalism.

This sense of nationhood, or “becoming national,” emerges out of a variety of developments.

2

Benedict Anderson traces it to the birth of “print capitalism” in Europe, first in Latin and then in more local vernaculars, and the emerging “possibility of a new imagined community, which in its basic morphology set the stage for the modern nation.”

3

Similarly, Ernest Gellner maintains that the spread of industrial social organization creates a certain level of homogeneity throughout society and in cultural norms, thus resulting in the emergence of the phenomenon of nationhood and, consequently, nationalism.

4

Similar material and cultural developments facilitated the social construction of nationality in the non-Western world as well, although here the deliberate role of individual personalities, whose resistance to colonial domination was often inspired in the name of a

nation,

was also important. Often either explicitly or in less conscious ways, these individuals mobilized people in the various cities and regions who already shared certain historical experiences and sociocultural characteristics.

In doing so, these emergent national leaders needed forums and institutions to spread their unifying messages more effectively, at times coercively. The forums often served as embryonic components of a state, through which the national project was formulated among an elite, then articulated for the masses and upheld against challenges from within and from the outside. The phenomenon of the state, therefore—or, for stateless nations, protostate organizations such as national liberation parties—is central to the development and spread of nationalist sentiments. Centrality of the state became all the more crucial in the early twentieth century, when several multinational empires—most notably the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires—collapsed and gave rise to new national entities. In each of these newly independent or “successor” states, the idea of national independence had been a largely elite invention up until that point. Take, for example, the challenges facing the stewards of

Turkish independence upon the death of the Ottomans. As Bernard Lewis observes, “This new idea of the territorial state of Turkey, the fatherland of a nation called the Turks, was by no means easy to inculcate in a people so long accustomed to religious and dynastic royalties. The frontiers of the new state were themselves new and unfamiliar, entirely devoid of the emotional impact made by the beloved outlines of their country on generations of schoolboys in the West; even the name of the country, Türkiye, was new in conception and alien in form, so much so that the Turkish authorities hesitated for a while between variant spellings of it.”

5

Slightly to the west of Turkey, leaders of the newly independent countries of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary grappled with nearly identical dilemmas. A few decades later, so did the champions of African independence.

The popular inculcation of the idea of the new nation, and the defense of its largely artificial boundaries, is the task of the state. In fact, the state and frequently the primary actors within it, the “leaders,” emerge as the chief protectors and embodiment of national independence. It is no accident that at certain points in history, depending on the prevailing conditions within the nation and the agendas and capabilities of the state and its leaders, nationalism can boil over into jingoist militarism. At the opposite extreme, nationalism may remain dormant and untapped.

Nationalist sentiments may also be awakened by developments elsewhere. Nationalism can at times assume an

antithetical

nature, being formed and expressed in opposition to something. That something is often the expressed identity of another nation—another nationalism—or an external development that awakens, or reawakens, a sense of national pride and self-assertion. This is precisely what occurred in relation to both Zionist and Palestinian national identities. Zionism, it will be seen shortly, originated in the wake of and in reaction to growing anti-Semitism in Europe in the mid-to late 1800s. In the early decades of the 1900s, this new sense of national identity, by then affixed to geographic Palestine, jolted and awakened a Palestinian identity that had lain dormant for some time.

6

In a sense, “Arabness and Jewishness were formulated as nationalist concepts in historically unprecedented ways.”

7

In the larger Middle East, several different nationalist sentiments emerged, some sequentially, some concurrently in different countries of the region, and still others in an overlapping manner among different peoples within the same geographic territory. This latter form of nationalism developed within the Palestinian and Zionist communities in relation to the same piece of land. Earlier, from approximately the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s, Ottoman nationalism—or, more accurately, Ottomanism—held

sway throughout Ottoman territories, articulated in and dictated from Istanbul. By most accounts, Ottomanism was successful in instilling a communal sense of belonging to an expansive

umma

(Muslim community) and in maintaining loyalty to the Ottoman state and to the sultan. But by the mid-nineteenth century, as the influence and intrigue of European powers in Ottoman territories gradually increased, especially in the Balkans, the sense of national belonging as articulated from Istanbul—of belonging to an imperial, caliphal, Ottoman nation—began to decline. In its place, more localized forms of nationalism, revolving around locally more resonant symbols and less expansive territories, emerged. At this stage Ottomanism was gradually supplanted by Turkish nationalism in Anatolia and by Arabism elsewhere in the empire. The rise and nature of Arabism, or Arab nationalism, differed from region to region in intensity, origin, and precise character.

8

The earliest forms of Arab nationalism, as envisaged politically by the likes of King Hussein of Hijaz and his sons, included the Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire from the boundaries of Iran in the east to Turkey in the north, the Red Sea in the west, and Egypt in the southwest.

9

Hussein’s two sons, Faisal and Abdullah, who ruled over Syria (briefly) and eventually Iraq and Transjordan, had still more narrow conceptions of national identity and nationhood, though less out of ideological convictions than as a result of European mapmaking. Although the Ottomans allowed for considerable local autonomy, these territorially more specific versions of nationalism were more steeped in local, Arab (non-Turkic) social dynamics and cultural lore and symbolism.

10

Political manifestations of Arab nationalism were eclipsed for a few years by the more powerful forces of European colonialism, which, among other things, redrew the map of the Middle East for their own administrative and political convenience. Nevertheless, during the period of European political and military domination, and largely in reaction to it, a number of Arab intellectuals began articulating nationalist ideals and sentiments through the publication of books and journals.

11

Once European colonialism started retreating in the 1940s, Arab nationalism regained the opportunity to assert itself politically, this time in a much more vocal and virulent manner. The Europeans had created new Arab countries, leaving behind new states for each country, and now the stewards of these new states called on their respective nations to awaken to their full national potential. By the mid-twentieth century, there were such brands of nationalism as Egyptian, Iraqi, Syrian, Lebanese, Jordanian, and Libyan. Turkish and Iranian nationalisms had emerged a few decades earlier, articulated by the Kemalist and Pahlavi states, respectively. Hopes of resurrecting earlier, territorially more

expansive conceptions of Arab nationalism—what came to be known as “Pan-Arabism”—lingered, at times motivated by more immediate political considerations. They led to territorial and political unions of Egypt and Syria (1958–61), as well as an ambitious proposed federation of Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Sudan in 1971 and another proposed union of Syria and Iraq in 1979, neither of which materialized. These supranational creations were unrealistic and at best impermanent. Their failure points to the

powers of the more localized manifestations of Arab

nations

and the corresponding force of more locally focused nationalisms.