The Monkey Grammarian (18 page)

With stones, little hammers, and other objects, the acolytes began to strike the iron bars hanging from the ceiling. A man appeared—wearing a coarse-woven garment, with a mask over his face, a helmet, and a rod simulating a lance. He may have represented one of the warrior monkeys who accompanied Hanum n and Sugriva on their expedition to Lanka. The acolytes continued to strike the iron bars, and a powerful and implacable storm of sound rained down on the heads of the multitude eddying about below. At the foot of the banyan tree a dozen

n and Sugriva on their expedition to Lanka. The acolytes continued to strike the iron bars, and a powerful and implacable storm of sound rained down on the heads of the multitude eddying about below. At the foot of the banyan tree a dozen

sadhus

had congregated, all of them advanced in years, with shaved heads or long tangled locks coated with red dust, wavy white beards, their faces smeared with paint and their foreheads decorated with signs: vertical and horizontal stripes, circles, half-moons, tridents. Some of them were decked in white or saffron robes, others were naked, their bodies covered with ashes or cow dung, their genitals protected by a cotton pouch hanging from a cord that served as a belt. Lying stretched out on the ground, they were smoking, drinking tea or milk or bhang, laughing, conversing, praying in a half-whisper, or simply lying there silently. On hearing the sound of the bars being struck and the confused murmur of the priests’ voices chanting hymns overhead, they all stood up and without forewarning, as though obeying an order that no one save them had heard, with blazing eyes and somnambulistic gestures— the gestures of someone walking in his sleep and moving about very slowly, like a diver at the bottom of the sea— they formed a circle and began to sing and dance. The crowd gathered round and followed their movements, transfixed, with smiling, respectful fascination. Leaps and chants, the flutter of bright-colored rags and sparkling tatters, luxurious poverty, flashes of splendor and wretchedness, a dance of invalids and nonagenarians, the gestures of drowned men and illuminati, dry branches of the human tree that the wind rips off and carries away, a flight of puppets, the rasping voices of stones falling in blind wells, the piercing voices of panes of glass shattering, acts of homage paid by death to life.

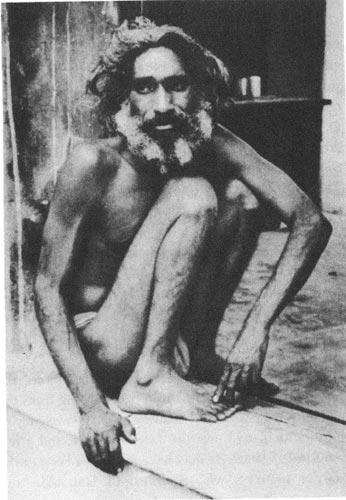

A s dhu in the sanctuary of Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

dhu in the sanctuary of Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

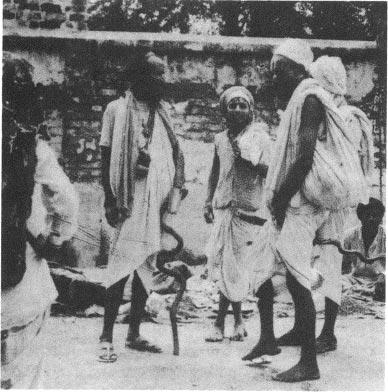

A s dhu and pilgrim near Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

dhu and pilgrim near Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

The multitude was a lake of quiet movements, one vast warm undulation. The springs had let go, the tensions were disappearing, to exist was to spread out, to overflow, to turn liquid, to return to the primordial water, to the ocean that is the mother of all. The dance of the

sadhus

, the chants of the officiants, the cries and exclamations of the multitude were bubbles rising from the great lake lying hypnotized beneath the metallic rain brought forth by the acolytes as they struck the iron bars. In the sky overhead, insensible to the movements of the hordes of people jammed together in the courtyard and to their rites, the crows, the blackbirds, the vultures, and the parakeets imperturbably continued their flights, their disputes, and their lovemaking. A limpid, naked sky. The air too had ceased to move. Calm and indifference. A deceptive repose made up of thousands upon thousands of imperceptible changes and movements: although it appeared that the light had halted forever on the pink scar on the wall, the stone was throbbing, breathing, it was alive, its scar was becoming more and more inflamed until finally it turned into a great gaping red wound, and just as this smoldering coal was about to burst into flame, it changed its mind, contracted little by little, withdrew into itself, buried itself in its dying ardor, simply a black stain spreading over the wall now. It was the same with the sky, with the courtyard, with the crowd. Evening came amid the fallen brightnesses, submerged the flat-topped hills, blinded the reflections, turned the transparencies opaque. Congregating on the balconies from which, in other times, the princes and their wives contemplated the spectacles taking place on the esplanade, hundreds and hundreds of monkeys, with that curiosity of theirs that is a terrible form of the indifference of the universe, watched the feast being celebrated by the men down below.

When spoken or written, words advance and inscribe themselves one after the other upon the space that is theirs: the sheet of paper, the wall of air. They advance, they go from here to there, they trace a path: they go by, they are time. Although they never stop moving from one point to another and thus describe a horizontal or vertical line (depending on the nature of the writing), from another perspective, the simultaneous or converging one which is that of poetry, the phrases that go to make up a text appear as great motionless, transparent blocks: the text does not go anywhere, language ceases to flow. A dizzying repose because it is a fabric woven of nothing but clarity: each page reflects all the others, and each one is the echo of the one that precedes or follows it—the echo and the answer, rhyme and metaphor. There is no end and no beginning: everything is center. Neither before nor after, neither in front of nor behind, neither inside nor outside: everything is in everything. Like a spiral seashell, all times are this time now, which is nothing except, like cut crystal, the momentary condensation of other times into an insubstantial clarity. Condensation and dispersion, the secret sign that the now makes to itself just as it dissipates. Simultaneous perspective does not look upon language as a path because it is not the search for meaning that orients it. Poetry does not attempt to discover what there is at the end of the road; it conceives of the text as a series of transparent strata within which the various parts—the different verbal and semantic currents—produce momentary configurations as they intertwine or break apart, as they reflect each other or efface each other. Poetry contemplates itself, fuses with itself, and obliterates itself in the crystallizations of language. Apparitions, metamorphoses, volatilizations, precipitations of presences. These configurations are crystallized time: although they are perpetually in motion, they always point to the same hour—the hour of change. Each one of them contains all the others, each one is inside the others: change is only the oft-repeated and ever-different metaphor of identity.

When spoken or written, words advance and inscribe themselves one after the other upon the space that is theirs: the sheet of paper, the wall of air. They advance, they go from here to there, they trace a path: they go by, they are time. Although they never stop moving from one point to another and thus describe a horizontal or vertical line (depending on the nature of the writing), from another perspective, the simultaneous or converging one which is that of poetry, the phrases that go to make up a text appear as great motionless, transparent blocks: the text does not go anywhere, language ceases to flow. A dizzying repose because it is a fabric woven of nothing but clarity: each page reflects all the others, and each one is the echo of the one that precedes or follows it—the echo and the answer, rhyme and metaphor. There is no end and no beginning: everything is center. Neither before nor after, neither in front of nor behind, neither inside nor outside: everything is in everything. Like a spiral seashell, all times are this time now, which is nothing except, like cut crystal, the momentary condensation of other times into an insubstantial clarity. Condensation and dispersion, the secret sign that the now makes to itself just as it dissipates. Simultaneous perspective does not look upon language as a path because it is not the search for meaning that orients it. Poetry does not attempt to discover what there is at the end of the road; it conceives of the text as a series of transparent strata within which the various parts—the different verbal and semantic currents—produce momentary configurations as they intertwine or break apart, as they reflect each other or efface each other. Poetry contemplates itself, fuses with itself, and obliterates itself in the crystallizations of language. Apparitions, metamorphoses, volatilizations, precipitations of presences. These configurations are crystallized time: although they are perpetually in motion, they always point to the same hour—the hour of change. Each one of them contains all the others, each one is inside the others: change is only the oft-repeated and ever-different metaphor of identity.

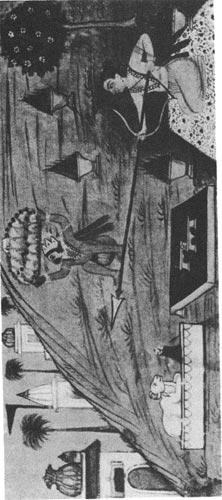

Bharat transporting Hanum n to battlefield with his magic arrow, Oudh, 19th century.

n to battlefield with his magic arrow, Oudh, 19th century.