The Myst Reader (112 page)

Authors: Robyn Miller

LATER, WHEN THEY WERE ALL SITTING IN GADREN’S

cabin talking, someone mentioned the old man who lived alone on an island on the lake.

“An old man?” Atrus asked, interested.

“His name is Tergahn,” Gadren’s wife, Ferras, said before her husband could speak, “and he keeps bitterness for a wife.”

“He lives a hermit’s life,” Gadren said, frowning at his wife.

“Hermit indeed,” Ferras said, making a face back at her husband. “If we see the old stick once a year that’s oftener than most.”

“Is he D’ni?”

“Oh, indeed,” Gadren said. “A fine old gentleman he must have been. A Master, I’d guess, though of what Guild I wouldn’t know.”

“You didn’t know him, then?”

“Not at all. You see, he was passing our house when it all happened. The great cavern was filling up with that evil gas and there was no time for him to get back to his own district. My father, rest his soul, saw him and asked him in. He linked here with us.”

“And afterward? Did he not try to return?”

Gadren looked down. “We did not let him. He wanted to, but my father would let no one use the Linking Book. Not for a year. Then he went himself. After that, no one went.”

“And the Linking Book?”

“My father destroyed it.”

Atrus thought a moment, then stood. “I would like to meet this Tergahn and talk with him. Try to persuade him to come with us.”

“You can try,” Ferras said, ignoring her husband’s frown, “but I doubt you’ll get a word out of him. He’ll scuttle away like a squirrel and hide in the woods behind his cabin till you’re gone.”

“He’s that unsociable?”

“Oh, aye,” Gadren said with a laugh. “But if you’re keen to meet with him, I’ll row you there myself, Atrus. And on the way you can tell me what’s been happening in D’ni.”

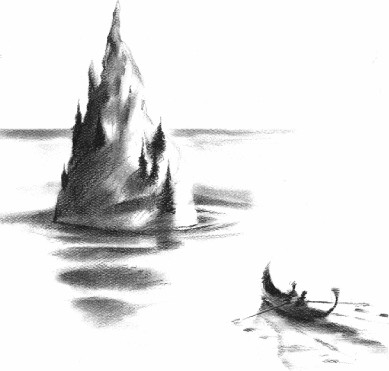

THEIR DESTINATION WAS AT THE FAR END OF

the lake, over a mile from the village. The lake curved sharply here, ending in a massive wall of dark granite. The island lay beneath that daunting barrier, its wooded slopes reflected in the dark mirror of the lake.

As they rowed toward it, that mirror shimmered and distorted.

A narrow stone jetty reached out into the lake. From there a path led up among the trees. Tergahn’s cabin was near the top of the island, enclosed by the darkness of the wood. It was silent on those slopes. Silent and dark.

Standing just below the cabin, staring up into its shadowed porch, Gadren cupped his hands to his mouth and hailed the old man.

“Tergahn? Tergahn! You have a visitor.”

“I know.”

The words startled them. They turned to find the old man behind them, less than ten paces away.

Tergahn was not simply old, he looked ancient. His face was deeply lined, his eyes sunken in their orbits. Not a shred of hair was on his head, the pate of which was mottled with age, yet he held himself upright and there was something about his bearing, a sharpness in his eyes behind the lenses, that suggested he was still some distance from senility.

Atrus took a breath, then offered his hands. “Master Tergahn, I am honored to meet you. My name is Atrus.”

The old man stared at him a while, then shook his head. “No, no … you’re far too young.”

“Atrus,” he repeated, “of the Guild of Writers, son of Gehn, grandson of Master Aitrus.”

The old man’s eyes blinked at that last name. “And Ti’ana?”

“Ti’ana was my grandmother.”

Tergahn fell silent. He looked down at the ground for a long time, as if lost in his thoughts, then, finally, he looked up again. “Ahh,” he said. “Ahh.”

“Are you all right, Master Tergahn?” Gadren asked, concerned for him, but Tergahn gave an impatient gesture with his hand.

“Leave me,” he said, a hint of bad temper in his voice. “I need to talk to the boy.”

Atrus looked about, then realized that Tergahn meant him.

“Well?” Tergahn said, staring pointedly at Gadren. “Haven’t you a boat to look after?” Then, turning, pulling his cloak tighter about him, he stomped past Atrus and up the slope.

“Come,” he said, stepping up into the shadows of the porch. “Come, Atrus, son of Gehn. We need to talk.”

THE INTERIOR OF THE CABIN WAS SMALL AND

dark, a bulging knapsack sat beside the open door, its drawstring tied.

At the center of the room was a table with a single chair. Standing on the far side of that table, Tergahn put his arm out, indicating that Atrus should be seated.

There were shelves of books on the walls, and prints. Things that must have been there before Tergahn came.

Declining the offer of the chair, Atrus stood there, facing Tergahn across the table.

“Forgive me, Master Tergahn, but I sensed just now, when I mentioned my grandfather’s name, that you knew him.”

“I knew

of

him. He was a good man and an excellent Guildsman.” Tergahn stared at Atrus intently a moment. “Indeed, you’re very like him now that I come to look.”

Atrus took a long breath. “We came here …”

“To ask us to return?” Tergahn nodded. “Yes, yes, I understand all that. And I’m ready.”

“Ready?” For once Atrus could not keep the surprise from his voice. “But surely you’ll want time to pack?”

“I have already packed,” Tergahn answered, indicating the bag beside the door. “When I heard the boat coming and saw you on it, I knew.”

“You

knew

?”

“Oh, yes. I’ve been waiting a long time now. Seventy years in this cursed place. But I knew you would come eventually. Or someone like you.”

“And all this?” Atrus, gesturing toward the books, the various objects scattered on shelves about the room.

“Forget them,” Tergahn answered. “They were never mine. Now come, Atrus. I will not wait another hour in this place.”

THE FINAL SEARCHES TOOK MUCH LONGER

than the earlier ones. As Atrus had foreseen, the majority of them proved to be dangerous, unstable Ages, and the E.V. suit found much further use. But there were successes. One Book in particular—an old, rather decrepit volume for which Atrus had held very little hope—yielded up a colony of three hundred men, women, and children. This and a second, much smaller, group—from a Book that had been partly damaged in the Fall—swelled the population of New D’ni to just over eighteen hundred souls. On the evening of that final search, eight weeks after they had linked into Sedona, Atrus threw a feast to celebrate.

That evening was one of the high points of their venture, and there was much talk of—and many toasts to—the rebirth of D’ni. Yet in the more sober atmosphere of the next morning, all there realized the scale of the task confronting them.

When a great empire falls, it is not easy trying to lift the lifeless carcass back onto its feet. Even if many more had survived, it would have been difficult; as it was, there were not enough of them to fill a single district, let alone a great city such as D’ni. At the final count there were 618 adult males, and of them a mere 17 had been Guildsmen.

Atrus, making his final reckoning before beginning the next phase of the reconstruction, knew that one thing and one thing only could carry them through: hard work.

Each night he fell into his bed, exhausted. Day after day he felt this way, like a machine that cannot rest unless it is switched off completely. Each night he would sleep the sleep of the dead, and each morning he would rise to take on his burden once again. And little by little things got done.

But never enough. Never a tenth of what he wanted to achieve.

One morning Atrus wandered out to see how Master Tamon was faring. Tamon had cleared most of the fallen masonry from the site, exposing the interior of the ancient Guild House, and now he was about to begin the most delicate phase of the operation: lifting an internal wall that had come down in what had been the dining hall. The fallen wall had smashed through the mosaic floor in several places, revealing the hypocaust beneath it. Master Tamon’s problem was how to clear away the massive chunks of fallen wall without the damaged floor collapsing beneath his team as they worked.

After much consideration, he had decided that this was a simple mining problem—an exercise in shoring up and chipping out—and therefore he had called in “Young Jenniran,” a sprightly ninety-year-old who had been a cadet in the Guild of Miners when D’ni fell. When Atrus arrived, the two men were standing, their heads together, on one side of the site, a sheet of hand-drawn diagrams held between them as they debated the matter.

“Ah, Atrus!” Tamon exclaimed. “Perhaps you can help us resolve something.”

“Is there another problem?”

“Not so much a problem,” Jenniran said, “as a small difference of opinion.”

“Go on,” said Atrus patiently.

“Well … Master Tamon wishes to lift the wall and save the floor. And I can see why. It’s a very beautiful piece of mosaic. But to do so, we would have to get beneath the floor and prop it up, and that will take days, possibly weeks, of hard work and involve considerable risks for those undertaking the task.”

Atrus nodded. “And your alternative?”

Jenniran glanced at Tamon, then went on. “I say let’s give up the floor. Let’s drop weights on it and smash the whole thing through, then clear up the mess. It will not only save us precious days but cut out any risk of injury.”

“But the floor, Atrus! Look at it!”

Atrus looked. He could see only the edges, and they were covered in a fine layer of dust, but he had seen the diagrams of the Guild House and remembered this mosaic well. It would be a great shame to lose it. Then again, Jenniran had a point about the safety element, and the floor

was

badly damaged as it was.

And then there was so much else to do. So much to clear away. So much to repair and make good. Thinking that, Atrus made his decision.

“Can I have a word, Master Tamon?” he said, laying an arm about the older man’s shoulders and turning him away.