The Myst Reader (36 page)

Authors: Robyn Miller

Not that the rock was like real rock. It had a glassy look to it, as if it were made of gelatin, yet it had the warm, textured feel of wood. Most surprising of all, it smelled … Atrus sniffed, then shook his head, amazed … of roses and camphor.

Everywhere he looked, forms met and merged, the barriers that normally existed between things dissolved away here, as in a dream.

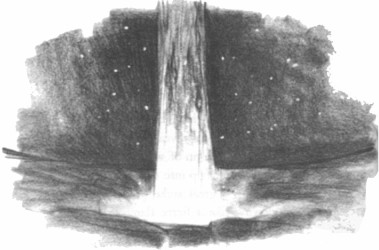

He shivered then looked up, pointing out toward the great chute of water that cascaded endlessly into the night sky.

“Where does it go?”

She laughed; the softest, gentlest laugh he’d ever heard. “Did you ever wonder what it would be like to go swimming out among the stars?”

“Swimming?” For a moment he thought of Anna and the cleft, that evening after the desert rain.

“Yes,” she said wistfully. “If it is my dream, we could fall into the night and be cradled by stars and still return to the place where we began.”

Atrus stared at her, wondering what she meant. Sometimes she was like her book—beautiful and poetic, yes, and incomprehensible, too.

“I’m not very lucky with water,” he said, making her laugh. “But this …” He turned, raising his arms to indicate the Age she’d made. “I can’t understand it.” He looked to her, shaking his head in amazement. “I just can’t see how it works.”

He looked about him, disconcerted by the way a bright blue snakelike creature split in two as it brushed against his arm, then split again and again, until there was a whole school of tiny snakes, swimming with identical motions in a tight formation.

“Did you

imagine

all of this?”

“Most of it,” she answered, walking past him, then stooping to pluck something from the ground close by. “Some of it I can’t remember writing. It’s almost like I stop thinking and just …

write

.”

She turned back, offering something to him. It was a flower. But not just a flower. As he went to take it from her, it seemed to flow toward his hand and rub against him, like a kitten brushing against its owner’s legs.

Atrus moved back.

“What is it?” she asked.

“I don’t know.” He smiled. “It’s just strange, that’s all.”

Catherine bent down and put the flower down carefully, then looked at him and smiled. “There’s nothing here that’s harmful. You’re safe here, Atrus. I promise you.”

Maybe so. But he still felt ill at ease. Nothing here behaved as it ought to behave. Wherever he looked the rules of normality were broken. This was an Age where the laws had been stood on their head. By rights it ought not to exist, and yet it did. So what did that mean? Was it as Catherine had said? Did some other set of laws—laws not discovered by the D’ni—prevail here? Or was this simply an anomaly?

Catherine straightened up, then put out her hand to him. “Come. Let me show you something.”

He walked down the slope with her until he stood only a few yards from the edge. Beyond it there was nothing. Nothing but the glow far below them, and the water, spewing up out of the center of that brightness.

“Here,” she said, handing him something small, smooth, and flat.

Atrus looked at it. It was a polished piece of stone, small enough to fit into his hand.

“Well?” she said. “Have you never skimmed a stone before?”

He looked to her, then swung his arm back and cast the stone across the darkness, imagining he was skimming it across the surface of a pond.

The stone skimmed rapidly across the vacant air, and then, as if it had suddenly hit a rock, soared in a steep curve upward, finally disappearing into that mighty rush of water.

Atrus stared, openmouthed, as he lost it in that mighty torrent, then turned, to find that Catherine was laughing softly.

“Your face!”

Atrus snapped his mouth shut, then looked back. He found that he wanted to do it again—to see the stone skim across the emptiness then soar.

“Where does it go?”

“Come,” she said, taking his hand again. “I’ll show you.”

THE TUNNEL THROUGH WHICH THEY WALKED

was small—just big enough for them to walk upright—and perfectly round, like a wormhole through a giant apple, the passage unevenly lit by some property within the rock itself. It led down, continually curving, until it seemed as though they must be walking on the ceiling. And then they came out. Out into brilliant daylight. Out into a landscape as amazing as the one they had left at the far end of the tunnel.

Atrus winced, his eyes pained by the sudden light, and pulled his glasses on, then straightened, looking out.

Just as the dark side had been strange, so this—the bright side of Catherine’s nature, as he saw it—was wonderful. They stood at the top of a great slope—a large rocky hill in the midst of an ocean, one of several set in a rough circle—each hill carpeted with bright, gorgeously scented flowers over which a million butterflies danced and fluttered.

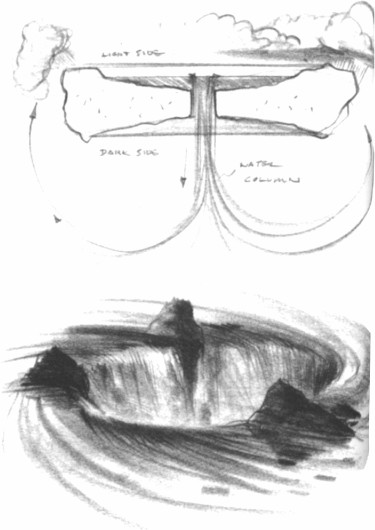

And at the very center of that circle of rocklike hills, a great ring-shaped waterfall rushed inward at an angle, toward a single central point far below. Directly over that huge vortex, flickering in and out of visibility, were twisting, vertical ribbons of fast-moving cloud that appeared high up in the air then vanished quickly into the mouth of that great circular falls.

With a shock of recognition, Atrus understood. “We’re on the other side! It’s the source of the great torrent … it falls

through

…”

And even as he said it, his mouth fell open with wonder.

But how? What physical mechanism was involved? For he knew—

knew

, with a sudden, absolute certainty—that if this existed, then there was a physical reason why it existed. This did not break the D’ni laws, it merely twisted them; pushed them to their limits.

He looked to Catherine, a sudden admiration in his eyes.

“This is beautiful. I never guessed …”

She took his hand. “There’s more. Would you like to see?”

“Yes.”

“Out there,” she said, pointing, directing his eyes toward the horizon.

Atrus stared. Huge thunderclouds massed at the horizon, rising up into the sky like steam from a boiling pot. Incredible thunderstorms, their noise muted by distance, filled the air out there, the whole of the horizon, as far as he could see to left and right, filled with flickering lightning.

It completely surrounds the torus

, he realized, turning, looking back at the great hole in the ocean, remembering the great jet of water on the far side of that massive hole. There seemed to be two separate forces at work here—one a jet stream force and the other a ring force to which the water was attracted.

Atrus blinked, then looked to Catherine. “You put most of the mass of the torus at its outer edge, didn’t you?”

She simply smiled at him.

“So the gravity …” Atrus paused, his right fist clenched intently, frown lines etched deep in his brow. “That circle of gravity …

forces

the water through the central hole … then some other force sucks it up into the sky, where it fans out … still captured by the gravitational field of the torus, and falls down the outer edges of that field …

right?

”

She simply smiled at him.

“And as it slowly falls, it forms clouds and the clouds cause the storms and …”

It was impressive. In fact, now that he partly understood it, it was even more impressive than he’d first thought.

He turned, standing, looking about him, then stopped dead. Just across from him was a patch of flowers, nestled in among the lush grass. He walked across, climbing the slope until he stood among them.

Flowers. Blue flowers. Thousands of tiny, delicate blue flowers with tiny, starlike petals and velvet dark stamen.

Moved by the sight, he stooped and plucked one, holding it to his nose, then looked to her.

“How did you know?”

“Know?” Catherine’s brow wrinkled in puzzlement. “Know what?”

“I thought … No, it doesn’t matter.” Then, changing the subject, “What are you to my father?”

She looked down. “I am his servant. One of his Guild members …”

He looked at her, knowing there was more, but afraid to ask.

After a moment, she spoke again. “I am to be married to him.”

“Married?”

She nodded, unable to look at him.

Atrus sat heavily, the flowers all around him. He closed his fingers, squeezing the tiny, delicate bloom, then let it fall.

His head hung now and his eyes seemed desolate.

“He has commanded me,” she said, stepping closer. “Thirty days, Gehn said. There is to be a great ceremony on Riven … Age Five.”

He looked up, a bitter disappointment in his eyes.

She met his eyes clearly. “I’d rather die.”

Slowly, very slowly, understanding of what she’d said came to his face. “Then …”

“Then you must help me, Atrus. We have thirty days. Thirty days to change things.”

“And if we can’t?”

Catherine turned her head, looking about her at the Age she had written, then looked back at Atrus, her green eyes burning. Burning with such an intensity that he felt transfixed, frozen, utterly overwhelmed by this strange woman and the odd powers she possessed. And as she held his gaze, she reached out for his hand, clenching it tightly in her own, and spoke; her voice filling him with a sudden, almost impulsive confidence. “We can do wonders, you and I. Wonders.”

A

S THE SUN SLOWLY SET, ATRUS STOOD ON

the top of the tiny plateau, his glasses pulled down tightly over his eyes, his journal open in his hand, looking out across the Age he had written. Below him lay a cold, dark sea, its surface smooth like oil, or like a mirror blackened by age, its sterile waters filling the great bowl that lay between the bloodred sandstone cliffs.

On the shores of that great sea, the land was bare and empty; more desolate even than the desert he had known as a child. Titanic sandstone escarpments, carved by the action of wind and sun, stretched to the horizon on every side, their stark, bloodred shapes interspersed with jagged, night-black chasms.

He had written in the bare minimum this time. Enough to conduct his experiment and no more. Enough to see whether his theories about the flaws in the Age Five book were true or not.

He had built ten such Ages in the past few weeks. Two for each experiment. In this and one other he was testing whether the changes he sought to make in the orbital system of Age Five would have the desired effects, while in others he was experimenting with the structure of the tectonic plates beneath the planet’s crust, the type and strength of the oceanic currents, fluctuations in gravitational fields, and the composition of the crust itself.

What he had done, here and elsewhere, was to recreate the same underlying structures that he had found in the Age Five book, only incorporating specific minor alterations—additions mainly—to the way the thing was phrased. If that new phrasing was correct, then this Age was now stable. And if this was stable, then so would Age Five be once he had written the changes into the book.

Looking about him, he jotted down his observations, then, closing the journal, slipped it into his knapsack.