The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (16 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

Though the passage reads quite convincingly to one not familiar with the material evidence, it is fairly riddled with errors. The ‘interpretive gloss’ placed on the data amounts to a

tour-de-force

. With Baroque excess, the author shapes, twists, forces, and contorts the evidence so as to eliminate the slightest suspicion of a hiatus in settlement. Perhaps readers will care to revisit this citation at a later time, after reading this book. They will then find in it half a dozen glaring faults without difficulty. For those who may not wish to wait, I summarize those faults now, sentence-by-sentence, with brief comments.

– “Recent archaeological evidence shows that Nazareth was inhabited long before as well as during the early Roman period.”

Comment

: This appears to be an adaptation from Finegan: “In the light of recent archaeological evidence… that Nazareth was an old established site

long before the Early Roman period

and during it…”

[178]

(emphasis added). In fact, Nazareth was not inhabited in the Early Roman Period. Nor was it inhabited “long before” the Roman period, unless we have in mind the Bronze and Iron Ages and

not subsequent periods

(something neither implied nor obvious from the citation). Thus, both Finegan’s and NIDBA’s statements are incorrect in one sense and misleading in another. They ignore the possibility of a hiatus in settlement.

– “This is evidenced by the ancient skull found near the town as well as by Middle Bronze-Age pottery from burial caves in the upper part of the city. Also, near the Church of the Annunciation there have been found grain silos of the type that were as early as the Chalcolithic Age but in which

the earliest

pottery

was of Iron II…” (emphasis added).

Comment:

The “earliest pottery” claim is now familiar from our dissection of Finegan’s article above (pp. 28–30), and this sentence also appears to be borrowed from that source.

[179]

The final clause is a restatement of the Bagatti-Finegan insinuation of continuous habitation, namely, that evidence at Nazareth postdates the Iron period.

– “Other pottery there consisted of a little from the Hellenistic period, more from the Roman and most from the Byzantine period.”

Comment

: As mentioned above, there is no pottery from the Nazareth basin dating to the Hellenistic period. This will be shown in Chapter Three. The lack of Hellenistic evidence at Nazareth effectively doubles the hiatus in settlement from four to eight centuries.

– “Of the twenty-three tombs found

c

. 450 m (500 yd.) from the church most were of the kokim type (

i.e.

, horizontal shafts or niches off a central chamber) known in Palestine from

c

. 200 BC and which became the standard Jewish type.”

Comment

: We will take up the subject of tombs later. Though the kokim (

kokh

, pl.

kokhim

) type of tomb was “known in Palestine from

c

. 200 BC,” at Nazareth use of this type of tomb begins much later, as will be proven by the artefacts found in them. They date the kokh tombs to Middle Roman and later times (see next point).

– “Two tombs had in them artifacts (lamps,

etc

.) to be dated from the first to fourth centuries A.D.”

Comment

: The Roman tomb evidence is datable to the second century of our era and thereafter. We shall see that most of it is III–IV century CE. The earliest Roman artefacts

may

date to later first century CE.

– “Four tombs sealed with rolling stones typical of the late Jewish period testify to a considerable Jewish community there in the Roman period.”

Comment

: Rolling stones are not found in Palestine before 70 CE. The only exceptions are rare monumental examples in Jerusalem (

e.g

., the tomb of Queen Helena of Adiabene).

[180]

Thus, every sentence of the above passage has inaccuracies, some egregious. The cumulative effect of all these errors, large and small, is an entirely false history of the site.

In a sense, Kopp’s prewar moving Nazareth hypothesis was safer for the Church than the continuous habitation doctrine first promulgated by Bagatti in 1955. The former was complex and difficult to comprehend – indeed, incomprehensible. Yet, an incomprehensible position is not immediately testable by evidence at hand. Since mid-century, the Church’s position has been verifiable, largely through evidence that Bagatti himself unearthed. The archaeologist rejected complexity, and chose to take the bull by the horns, as it were. He opted for the simple, direct solution, and for the grand line: Nazareth has existed since the dawn of history.

Taking the bull by the horns is a most precarious maneuver, and the slightest error often proves fatal. Yet, the Church’s position rests on not one, but twin horns, both dangerous to its interests. One horn is the evidence in the ground – or rather, the lack thereof – during the centuries following the Assyrian conquest. Bagatti himself must have recognized the sheer impossibility of the doctrine of continuous habitation the very year he first announced it. That was in 1955, the year he also dug the stratigraphic trench.

The second horn is a pattern of deception and invention in the literature, one which we have begun to reveal in these pages. That pattern includes global errors such as wholesale misdatings of evidence, as well as subtler errors such as cunningly-placed (and misplaced) words like “already,” “earliest,” and “uninterruptedly” at strategic places in the literature. All these strategems serve a simplistic, unrealistic, and even ludicrous position: Nazareth has continually existed for the past four thousand years.

There was no continuous habitation at Nazareth. The valley was empty of human settlement beginning with the Assyrian conquest in the late eighth century BCE, and it remained empty for many centuries thereafter. On fundamental issues of archaeology, Bagatti and the Church have planted themselves squarely and stridently on the wrong side of the fence. Understandably, they have done so for deeply-held doctrinal reasons. But a bull does not turn aside for doctrine, and nor should a reasoning reader. We have a right to know the facts about Nazareth, and the Great Hiatus is one of those facts.

Chapter Three

The

Hellenistic Renaissance Myth

The

Great Hiatus: Part II (332–63 BCE)

The Hellenistic Period

|

The fact that no hard evidence from the Babylonian and Persian Periods was found at Nazareth, despite much searching, led in some circles to the eventual abandonment of the continuous habitation doctrine. Towards the end of the twentieth century non-Catholic scholars began to suggest another possibility, one less fraught with difficulties, more consistent with the archaeological evidence, and also fully compatible with the gospel account. The Hellenistic renaissance doctrine, as I call it, acknowledges a hiatus in settlement at Nazareth but proposes that the hiatus ended several centuries before the time of Christ. This doctrine comes to grips with the lack of evidence following the Iron Age, as well as with the lack of mention of the village in the Old Testament, and in these ways it is more historically correct. At the same time, the Hellenistic renaissance doctrine conforms to the gospel assertion that Jesus came from Nazareth, and thus it upholds the inerrancy of scripture. Today, this view is widely held in Protestant circles. Yet, these pages will show that the Hellenistic renaissance doctrine has as little basis in fact as does the doctrine of continuous habitation.

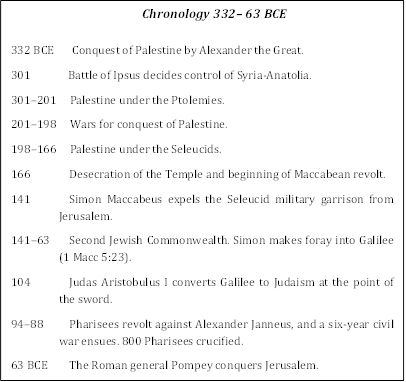

Many scholars divide the centuries following Alexander the Great’s conquest into two parts: the Hellenistic Period (332–

c

.166 BCE) and the Hasmonean Period (

c

. 166–63 BCE).

[181]

However, in this work the Hellenistic era encompasses both these periods, which are sometimes differentiated as “Early” and “Late” Hellenistic. When confusion might otherwise arise, I will date the century intended or use the word “Hasmonean.” Otherwise, “Hellenistic” is used generally to signify pre-Roman times in Palestine, namely, from the conquest of the land by Alexander to the Roman conquest under Pompey (332–63 BCE).

Thus, the Hellenistic period in Palestine comprises three successive political regimes: the Ptolemaic hegemony of the third century (301–201), several decades of Seleucid domination (201–166), and the fractious Hasmonean era (166–63). The Hellenistic Period is, of course, not synonymous with Greek influence which was known in the Levant long before Alexander and survived well after the first century BCE.

Ptolemaic times

In the early fifth century Persia represented the largest empire the world had ever known, stretching from India (Pakistan) to Libya. Accustomed to victory, the Achaemenids under Darius the Great suffered the first of many defeats at the hands of the Greeks in the Battle of Marathon (490 BCE). Xerxes, Darius’ eldest son, made a concerted attempt to revenge his father’s defeat, and though his armies managed to invade Greece and even to burn Athens (480), his fleet lost the Battle of Salamis, and his general, Mardonius, was defeated in the decisive battle of Plataea. The enormous effect of these victories on Greek society cannot be overestimated. “The Greeks,” writes Helmut Koester, “had successfully withstood the onslaught of an eastern superpower. The consciousness of the superiority of Greek education, Greek culture, and of the Greek gods formed not only the Greek mind, but also that of other nations, later including even the Romans, although they were to become the masters of the Greeks.”

[182]

The golden age of classical Greece followed upon the defeat of Persia, but the Peloponnesian Wars (431–404) were enormously destructive and costly to both Sparta and Athens. The fourth century witnessed increasing impoverishment of the Greek population. In 338 Philip of Macedon conquered Athens and brought an end to its glory, as Demosthenes noted at the time. The conquest of Persia beckoned, and Isocrates, then ninety years old, told Philip: “Once you have made the Persian subject to your rule, there is nothing left for you but to become a god.”

[183]

Philip was murdered in 336, and the lot of conquering Persia fell to his son, Alexander the Great, who was immediately proclaimed king of the Macedonians at the age of twenty. Alexander, a profound student of Greek ways, was educated by Aristotle himself. Within a year Alexander had suppressed revolts in Greece and crossed the Bosporus into Asia Minor, thus beginning his legendary conquests. In 333 he defeated the Persian King Darius at Issus (between Asia Minor and Syria), and then swept down the eastern Mediterranean seaboard easily conquering all in his path, with the exception of the island city of Tyre, which required an extended siege. In 332 Alexander conquered Palestine, and he may have visited Jerusalem. Egypt submitted to him without a battle, and the founding of Alexandria at the mouth of the Nile marked the creation of a vibrant new center of commerce and culture. In 331 Alexander defeated Darius a second time at Gaugamela (east of the upper Tigris), and this allowed him access to Mesopotamia. By 327 the conqueror had reached India. In 323 Alexander fell ill in Babylon and died, not yet thirty-three years old.

Alexander the Great failed to leave an heir and successor, and his vast kingdom fractured into three principle parts ruled by his Macedonian successors, the “Diadochi”: Greece under the Antigonids; Persia under the Seleucids; and Egypt under the Ptolemies. Syria, Palestine, and Phoenicia were of especial importance to the Seleucids, for they furnished strategic access to Mediterranean sea trade. In the two decades after Alexander’s death Palestine was repeatedly the venue of battles between the Diadochi, until in 301 BCE Ptolemy I Soter succeeded in annexing the land.

The seeds of deep divisions within Judaism were planted in the Ptolemaic period, divisions that came to a head in subsequent Seleucid and Maccabean times. One problem was monetary: the critical right to collect taxes in Judea on behalf of the Ptolemies was purchased in the mid-third century (and retained) by traditional enemies of Jerusalem, namely the Tobiads.

[184]

This family possessed ancestral lands in ‘foreign’ territory, namely in Ammon east of the River Jordan, and were allied with the anti-Jerusalem Samaritans.

[185]