The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (6 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

A second reason why no early habitations have been found may be that construction activity has removed many traces of earlier structures. Nazareth has been inhabited since the second century of our era. In the last eighteen centuries much Bronze, Iron , and Roman evidence has no doubt either been destroyed or covered over.

A third reason for the lack of pre-Byzantine structural remains is a startling fact revealed for the first time in this book—for many centuries after the Iron Age the Nazareth valley was uninhabited. These eras, which I refer to as the Great Hiatus, lasted from the Late Iron Age until Middle Roman times, an interval of approximately eight hundred years.

[41]

We are not in a position to examine dwellings or the contents of dwellings (wall foundations, domestic pottery

in situ

, hearths, ovens,

etc.

) until post-Roman times. The only structural remains that survive from the Bronze Age are tombs.

[42]

The artefacts found in them date to many different centuries, and show that there was habitation in the basin both in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages.

A chronology based on the movable finds from the Bronze and Iron Age tombs is presented in

Illus.1.5.

As the MB progresses the number of artefacts noticeably decreases, and four of the five Bronze Age tombs entirely cease to be used after the middle of the millennium. This could mean that there was a break in settlement at mid-millennium (see below). We cannot be sure, for Tomb 1 continues in use.

Illus. 1.3

shows that Bronze and Iron Age loci are concentrated in the same general vicinity, on the western side of the basin.

[43]

This may simply be because that is the only area where major excavations have been conducted. In any case, the material record tells us that there was settlement throughout the millennium, and in the same general vicinity. That settlement may have been continuous or may have suffered a dislocation at mid-millennium.

After about 800 years of use, Tomb 1 was finally abandoned. Iron Age material appears at new locations entirely unmixed with older Bronze Age artefacts, and it is different in character. These facts suggest that a new group of inhabitants entered the basin about 1200 BCE. Again, we cannot be sure. It may be that the inhabitants simply adopted new production techniques and wares as they entered the Iron Age.

Bagatti has published the preponderance of datings for the Bronze and Iron Age material from Nazareth, and many of his estimates are broad, as is evident from the long time spans in

Illus. 1.5

. A thorough redating of these artefacts by specialists is a desideratum. Father S. Loffreda dated sixteen Iron Age objects, and Fanny Vitto then reviewed many of Loffreda’s datings and assigned them more precisely to the eleventh century. It should be noted that

Illus. 1.5

represents only a portion of the finds. Many vessels are too fragmentary or damaged to date typologically, that is, by comparison with pottery from other places.

Despite the paucity of material and the imprecise dating of many of the objects, a general picture of Nazareth in the Bronze Age emerges. It is clear that the basin was occupied throughout the MB and LB, with the possibility of a break in settlement at mid-millennium.

[44]

The Bronze Age tombs at Nazareth

Bagatti designates these as Tombs 1, 7, 8, 80, and 81. Three are within a few meters of one another on Roman Catholic property, under and next to the present Church of the Annunciation (

Illus. 1.3

). Tomb 80 is about 60 m. south of the others, in an area that until recently was the Greek (Melchite) cemetery. It has since become a commercial district. Evidently, these four tombs were part of a Bronze Age necropolis. As for Tomb 81, it is separate from the others and located on the northeastern side of the Nazareth basin, in the modern suburb of Nazrat Illit (Upper Nazareth). It was excavated by the Israel Department of Antiquities in 1963.

[45]

Two short and practically identical notices regarding Tomb 81 are given in the

Revue Biblique

of 1963 and 1965. The former reads:

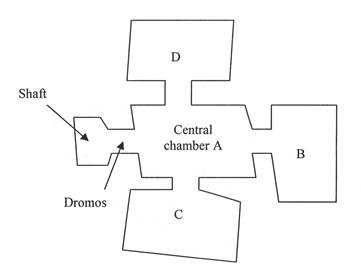

During some construction activity in Upper Nazareth, a burial grotto was discovered dating to the Middle Bronze I. Access to this grotto was by a shaft leading to a central chamber, from which three other chambers branched. The preponderance of pottery was found in the main room; the other chambers contained mostly bones. The pottery consists of “teapots” characteristic of the Middle Bronze I, two small jars with ring handles, and one large jar.

[46]

Illus.1.6: Plan of a typical Bronze Age shaft tomb at

Megiddo. (Redrawn from Kenyon)

The description of this tomb corresponds to the typical Bronze Age shaft tomb diagrammed above (

Illus.1.6

). Four or more of the tombs at Nazareth are of the shaft type,

[47]

which was the most common type of burial in Palestine from the second half of the fourth millennium until well into the Iron Age.

[48]

It was “almost rigidly stereotyped” (Kenyon).

[49]

The standard four-room plan of this type of tomb consisted of a descending entry shaft, a short entryway (dromos), and a central chamber from which three burial caves radiated, one on each side except the entrance. The small entryway was sealed with a stone, and the shaft subsequently filled in with earth or rubble.

The overall plan resembles a cross. The form is exemplified by Tomb 8 at Nazareth, discovered in 1955 by the Franciscans when digging the foundations for the new Church of the Annunciation.

[50]

Tomb 8 contained numerous Byzantine shards and a few of the Bronze period, which Bagatti dates generally to 2100–1850 BCE,

[51]

that is, to the same period as Tomb 81 (

Illus. 1.5

and Appendix 1).

[52]

The other four Bronze Age tombs which yielded artefacts are reported by Bagatti in his

Excavations

, though the archaeologist itemizes pottery and other movable objects from only three of them (Tombs 1, 7, and 80).

The reuse of tombs was customary in the Bronze Age, with multiple burials over several or many generations, as is evident from the long time spans in which the Nazareth tombs were used. Bodies were usually placed on the tomb floor, on their side and with limbs bent. Once decomposed, bones were moved to the back and sides of the chamber to make room for new bodies. Thus over time bones accumulated along the inner walls of the various chambers.

Of great interest to the archaeologist are the artefacts that were often placed in tombs along with the body, such as pottery, weapons, or glass objects. These items served several purposes. Some were associated with the deceased person while alive, and thus had sentimental value in the minds of the relatives. Some artefacts were associated with belief in an afterlife, such as bowls or jars with foodstuffs placed next to the body for nourishment of the deceased, or weapons for protection in the next world (or in the ongoing spiritual journey). On the other hand, artefacts might have inadvertently been left behind in the tomb, such as practical items belonging to relatives or workmen (

e.g.

oil lamps or tools). Like the bones of the corpses, these also eventually accumulated to the back and sides of the burial chambers. R. Hachlili has summarized typical funerary artefacts of the Middle Bronze Period:

The most common burial provisions were bowls and platters for foodstuffs, jugs for liquids, and juglets for oil and perfume… These provisions demonstrate that the deceased were thought to need nourishment and the protection afforded both by weapons and symbolically by colored and metal jewelry.

[53]

When a Bronze Age tomb is discovered that has not been robbed (a comparative rarity), a good deal of material can thus be found. This was the case with Tomb 1 at Nazareth.

Historical considerations

Do we have enough information to make further historical inferences regarding the Bronze Age at Nazareth? From the fact that five tombs all appear about the same time we can surmise that, in all likelihood, an extended family or group of families related by blood (Heb.

mishpacha,

“clan”) entered the Nazareth basin from the Jezreel Valley in the twenty-second century. The use of tombs reflects blood relations, for the tomb was a family affair. Certainly, only an extended family (

beit ’av

) afforded the manpower required to dig a shaft tomb. Blood ties, of course, have always been paramount in the Middle East, especially among groups on the move. The fact that five tombs in the Nazareth basin already exist by the end of the Intermediate Period shows that this quiet and fertile location enticed a substantial group of people to cease their wanderings and settle down.

Towards the beginning of the second millennium there is a great increase in the number of artefacts from these tombs (

Illus. 1.5

). This increase corresponds to the renaissance of settlement and culture that took place across Palestine in the MB IIA. The coast, the valleys, and the major urban centers (including Megiddo) were first resettled, followed by settlement in the hilly interior. By about 1750 the entire country had been settled,

[54]

and a flourishing settlement existed in the Nazareth basin.

There is considerable MB IIA pottery from Nazareth, and some of it probably came from Megiddo. “The most extensive pottery workshop area yet found in Palestine is on the east slope of the Megiddo mound,” writes B. Wood.

[55]

At least twelve kilns were found there. Elsewhere (p. 36) Wood notes that caves furnish excellent work areas for pottery production. This reminds us of Nazareth, for many caves dot the excavated area under and around the Church of the Annunciation. To my knowledge no kilns or potter’s wheels have been found at Nazareth.

[56]

Thus we cannot affirm that any of the pottery found there was produced on site. Given the limited area of excavations, however, this possibility cannot be ruled out.

After the MB IIA, which witnessed a peak in activity at Nazareth, the number of artefacts and also the number of tombs decreased. Tombs 8 and 81 were no longer used after about 1730 BCE, while Tomb 1 is represented by fewer finds. This diminution in the evidence corresponds with what we know from the rest of Canaan at the time. The lifespan of many MB IIA sites was short and limited to that period, and there was a noticeable abandonment and decline of settlements in the land at the end of the period. Kempinski suggests that much of the rural population was absorbed into cities and fortified settlements.

[57]

This may partly have been a reaction to Hyksos encroachment. The Hyksos (“rulers of foreign lands”) were Canaanites who gained control of Egypt from about 1680 to 1560 (Dynasty XV). They ruled Canaan as far north as the Jezreel valley.

[58]

Recollections of this period of foreign Canaanite ascendancy may underlie the accounts of Joseph’s authority in Egypt (Gen. 41:39

ff

). Indeed, the archaeological connection between Egypt and Canaan is particularly strong during this period (MB II B–C), and we find a wealth of Egyptian imports in Palestine (scarabs, faïence, alabaster vessels, bone-inlaid boxes). In the Nazareth valley, a scarab from Tomb 1 dates to the Hyksos period. Two alabaster jars from Tomb 80 from this time are also probably of Egyptian manufacture.

[59]

The Hyksos were expelled from Egypt by the Pharaoh Ahmose in the sixteenth century, and Egyptian control was then reasserted over the length and breadth of Canaan. At that time there was a disruption of settlement patterns on a large scale. Beginning about 1650, migration southwards seems to have been a reason for the increasing impoverishment of northern Canaan. The termination in use of four tombs at Nazareth about this time fits the broad historical context. There may have been a dislocation or great attrition in the settlement at the end of MB IIC. “The end of [the MB],” writes William Dever, “saw virtually every site in Palestine violently destroyed, probably in connection with the expulsion of the Hyksos in Egypt under the renascent Dynasty 18 kings,

ca.

1540–1480 B.C.”

[60]

Pharoah Thutmose I (reigned 1525–1512) extended the Egyptian sphere into Northern Syria and even crossed the River Euphrates. Megiddo and other Canaanite cities rebelled and supported the Mitanni to the north. As a result Pharaoh Thutmoses III (1504–1450) invaded Palestine and decisively smashed a coalition of 119 Canaanite and Syrian towns at the Battle of Megiddo about 1472. A description of that battle is proudly inscribed in hieroglyphic detail on the walls of the temple of Amun at Karnak, and in more abbreviated versions on stelae in Upper Egypt.