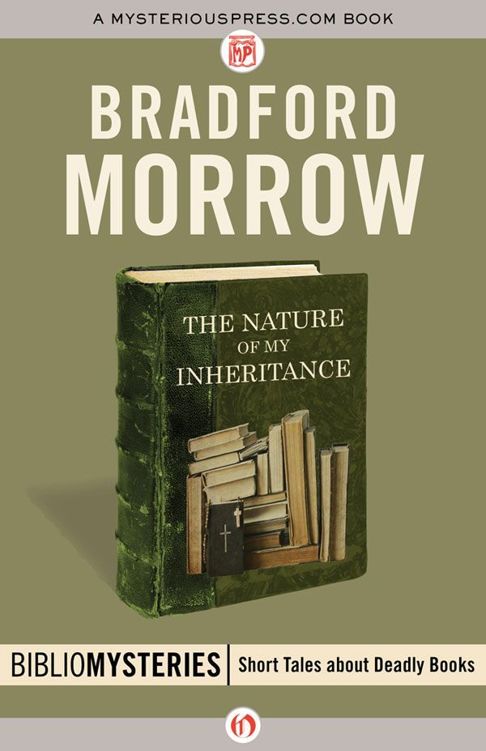

The Nature of My Inheritance

Read The Nature of My Inheritance Online

Authors: Bradford Morrow

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #British Detectives, #90 Minutes (44-64 Pages), #Literature & Fiction, #Traditional Detectives

The Nature of My Inheritance

Bradford Morrow

For Peter Straub

He that with headlong path

This certain order leaves,

An hapless end receives.

—Boethius,

The Consolation of Philosophy

In the wake of my father’s death, my inheritance

of over half a hundred Bibles offered

me no solace whatsoever, but instead served to

remind me what a godless son I was and had always

been. Like the contrarian children of police

officers who are sometimes driven to a life of

crime, and professors’ kids who become carefree

dropouts, my father’s devotion to his ministry

might well have been the impetus behind my

early secret embrace of atheism. In church, listening

to his Sunday sermons, as I sat in a pew

with my mother near the back of the sanctuary,

I nodded approvingly along with the rest of the

congregation when he hit upon this particularly

poignant scriptural point or that. But in all honesty,

my mind was a thousand light years away,

wallowing, at least usually, in smutty thoughts.

His last day in the pulpit, his last day on earth,

was no different. I cannot recall with precision

what lewd scenario I was playing out in my

head, but no doubt my juvenile pornography,

the witless daydream of a virgin, did not make a

pretty counterpoint with my father’s homily.

Why he bequeathed all these holy books to me

wouldn’t take a logician to reckon. My mother

spelled it out in plain English when we were in

the station wagon, along with my little brother,

Andrew, heading home after the funeral, and she

broke me the news about my odd inheritance.

“He worried about you day and night, you

know. He thought you should have them so you

might start reading and find your path to the

good Lord.”

I didn’t want to sound like the ingrate I was,

so suppressed my thought that a single Bible

would have been more than sufficient.

“Take care of them, Liam,” she continued.

“Do his memory proud.”

“I’ll try my best,” I said, trying to sound

earnest.

“And never forget how much he loved you,”

she finished, her eyes watering.

“I won’t, ever,” I said, in fact earnest, praying

she wasn’t about to crash our car into a curbside

tree.

My mom was a good soul and her intentions

were every bit as virtuous as my father’s. Both

of them were delusional, though, to think I was

going to sit in my attic room, put away my

comics, set aside my Xbox, turn off my television,

and switch over to Genesis. I was fourteen

back then, though I looked older, was recalcitrant

as a wild goat, locked in a losing battle with

raging hormones I didn’t understand, and while

I was capable of barricading myself behind a

bolted door to read every banned book I could

lay my hands on, I wasn’t about to launch into

the Scriptures. To please my poor distraught

mother, I did make the gesture of moving the

unwanted trove of Bibles up to my room, where

I double-shelved them alongside

Catcher in the

Rye, Candy, Lady Chatterley’s Lover,

and the rest

of my more profane paperbacks.

To my eye, the Holy Books were ugly monstrosities,

all sixty-three of them, bound variously

in worn black leather with yapped edges,

frayed buckram in a spectrum of serious colors,

tacky over-ornamented embossed leatherette.

Most of them were bulky, bigger than my own

neglected, pocket-sized copy, and as intimidating

in their girth as they were in their content,

tonnages of rules and regulations from on high,

miles of begets and begats. I was fascinated that

a dozen of them were bound in hard boards fastened shut with brass or silver clasps that needed

a key to open. I would have to look for the keys

sometime, I supposed, but since I had no intention

of reading them, there was no rush to go

hunting around the house. The whole passel of

stodgy books contained the same basic words,

the same crazy fairy tales, anyway, so what did I

care?

It needs to be said at the outset that my father,

the Reverend James Everett, minister at the

First Methodist Church of — , did not die from

natural causes. He was as hale as he was oldschool

handsome, with cleft chin, distinguished

wavy hair, and the coral-cheeked glow of an

adolescent rather than a man well into his forties,

the result of clean living and a lineage of

parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents,

all of whose middle names were Longevity. He

never smoked, not even a pensive evening pipe.

He drank exactly one glass of rum-spiked

eggnog every year before Christmas dinner,

which brightened his cheeks all the more, but

other than that and maybe a taste of communion

wine, he was as abstinent as Mary Baker

Eddy. In winter he shoveled our walk and our

next door neighbors’ in his oversize shearling

coat, and in summer mowed our lawn—me, I

was relegated to weeding my mother’s flower

garden—wearing a white short-sleeve shirt, clipon

bowtie, and straw boater hat. He was an exercise

nut who did a hundred sit-ups every

morning and a hundred push-ups before bed.

Above all, my father loved walking. He walked

here and walked there, and for longer distances,

much to my embarrassment, rather than drive

the family station wagon, a relic that dated back

to the Triassic, he rode a bicycle, his back as

straight as Elmira Gulch’s in

The Wizard of Oz

—

except with a faint smile on his face rather than

her witch’s frown. He was slim as a reed and

wiry as beef jerky. Some of my friends thought

he was a bit of a dork, and while I didn’t argue,

I knew that if he and any of their dads stripped

down to the waist and squared off, my father

would pummel them to pulp.

He seemed to have no enemies, my pop. It

was safe to say, or so all of us thought, that he

was one of the most liked and respected people

in the whole town. All who knew him, whether

they were members of his congregation or not,

from councilmen who sought his support during

elections to pimply grocery boys who happily

sacked his free-range steaks and organic

greens, agreed that my father was never meant

to die. My flaxen-haired and walnut-eyed Sunday

school teacher, Amanda was her name—a

name that rightly meant “worthy of love”—

confided in me when I was ten or eleven, “Your

dad is too good to go to hell, and too useful to

the Lord’s work here to go to heaven.” I think

that was one of the few times in my life I felt

sorry for him, a wingless angel with eternal

chewing gum on the soles of his shoes that allowed

him a future in neither some balmy paradise

nor a roasting inferno. Since I didn’t

believe in hell or heaven, though, my sorrow

quickly dissipated, was replaced by a mute

chuckle, and soon enough I was back to wondering

what gently curvy, sweet-spirited

Amanda, in her late teens, looked like when she

changed out of her clothes for bed.

And yet for all I looked down my freckled

nose at my reverend father’s zealous and traditionalist

beliefs, I missed him at the dinner table,

saying the same dull prayer before every meal,

passing me and my brother the meat, vegetable,

and starch dishes my mother cooked every

night. I missed him carefully reading our school

papers and suggesting areas for improvement. I

missed his attempts at being a regular-Joe father

who took his sons to college football games and

sat during our annual excursion to the Jersey

shore under a beach umbrella while Andrew and

I screeched and splashed around in the water,

wrestling in the frothy green breakers. Above all,

I missed his warm fatherly presence, like a fastgrowing,

scraggly rose vine might miss its fallen

trellis, despite the fact I had gone out of my way,

especially in recent years, to be a thorn in his

side.

At the funeral, a hundred mourners converged,

and I couldn’t help but overhear the rumors

about what might have caused him to fall

down the set of hardwood stairs that led from

the church chancellery to the basement after

giving a powerful sermon, by their lights anyway,

about the iniquity of avarice and the

blessed nature of giving. I knew the message of

this sermon well, to the point of nausea honestly,

as he and my mother discussed it after

dinner for a solid two weeks before he stepped

into the pulpit and delivered it on that doomed

day. Living in the household of a church father

means, for better or worse, having certain insights

into the mechanical workings, the practical

racks and pinions, of what transpires

behind the ethereal parts of any ministry. See,

being a clergyman isn’t all riding around on

puffy clouds and giving godly advice and just

generally being a beacon of hope and inspiration.

It is about keeping the tithes and offerings

flowing, like mother’s milk—oh, Amanda—so

staff wages can be paid, the church roof doesn’t

leak, the stained glass window that some local

punks saw fit to riddle with thrown rocks can

be repaired. The church is a nonprofit, so the

tax man never came knocking, but the insurance

man did, as well as many others whose

services were necessary to keep the ark afloat

and the fog machine running—at least, that’s

how I viewed things from my corner perch in

the peanut gallery, knowing leather-winged Lucifer

waited for me with open arms in the bowels

of Hades.

Simply and seriously put, my father was in

desperate need of money. Utility bills were overdue.

Last year’s steeple restoration remained

largely unpaid. The organ was in serious need

of an overhaul, and while it had sat idle for a

year or so, the piano that replaced it had steadily

gone out of tune. Even his own stipend was at

risk. I am sure that for every single problem I

knew about, watching my folks wringing their

hands on a nightly basis and sharing dire worries,

there were ten more deviltries utterly unknown

to me. One night, when I wandered in

on them, deliberately, I must admit, although

pretending I only just then heard about these

money issues, I offered to pick up a job after

school to help out.

“That’s good of you, Liam,” my father said.

“But I don’t think you understood what we were

talking about. No need for worry, everything’s

perfectly fine. You just stick to your schoolwork

and our lord savior will take care of the rest.”

Yes, he often spoke in such ecclesiastical

terms. If it weren’t so innocently offered, his

dimples flexing from nervousness and earnest

blue eyes searching for the confidence their

owner so badly wanted to convey to his eldest

son, I would have snorted, “Please, spare me!”

Or, worse, I would simply have laughed. I did

neither but left the room knowing that I had

tried to intercede and was rejected. Like a latterday

Pontius Pius, if a lot more reluctantly, I

washed my hands of the matter.

No one at the funeral said that my father was

pushed down the stairs, not in so many words.

Nobody whispered that he had borrowed himself

into debt, very deep debt, on behalf of the

church, not in so many words. And not one soul

suggested in so many words that in order to get

these loans, the church’s minister found himself

dealing with less than savory elements in the

community, churchgoing, god-fearing folks,

maybe, but people for whom the less-than-flattering

term “elements” was intended nonetheless.

The rumormongers were vaguer than all

that. It was from their overheard tones of voice

that I cobbled together what I knew, or thought

I knew, they were huddling about. One can say

the phrase “He’s such a good boy” so that it

means

the boy is good

or

the boy is bad

just by intoning

it differently. That much I understood, as

I wandered around, shadowed by my brother,

for whom our abrupt fatherlessness hadn’t yet

sunk in fully, accepting people’s condolences,

not trusting a single one of them, looking into

their eyes for a confession of some kind. I wasn’t

any more in my right mind than Drew, though

I felt I needed to put a brave face on my stunned

confusion. The way I figured it was that my father

was in the peak of health, athletic in his way,

cautious of diet, regular of habits, head on his

pillow at ten, up with the cock’s crow at six. In

church business he might have been stumbling,

but when walking down that flight of stairs after

his sermon that Sunday he did not trip, that

much I felt was irrefutable.