The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (23 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

Franklin Roosevelt’s plan for Social Security was a massive rethinking of the

state,

in the sense that the new system was much more than a simple safety net. It bound ordinary citizens to the federal government in a way that had not been imagined by the Founding Fathers. People came to rely on the state for their daily bread, and to take a much keener interest in the state itself. Traditional virtues—thrift, independence, self-reliance—were replaced with new virtues: political activism and gaming the system. In the second Roosevelt era, people came to expect the state to take care of things at home; later, they would come to expect the American government to build a better world outside the homeland, too.

While campaigning for presidency, Roosevelt had denounced Hoover as a spendthrift. The democratic platform during the campaign of 1932 called for, among other things, a drastic reduction of government spending by at least 25 percent, abolishing useless commissions and offices, a budget balanced annually, and a sound currency to be preserved at all hazards. But the country was in the throes of the Great Depression.

The causes of the depression have been hotly debated.They go beyond the scope of this book. But the consequences of the economic setback were to spur the nation toward its imperial mission. After the crash of the stock market in 1929, and after the country had entered a deflationary depression in the 1930s, there was little that a man sitting in a chair at 16 Pennsylvania Avenue could do to avert the aftermath of the debt bubble. “Every body tells me what is the matter, but nobody tells me what to do,” Roosevelt complained to his cabinet at one point early in his presidency. Soon Washington was flooded with do-gooders chomping at the bit to tell the president what to do. New books published as early as 1932 led the way. George Soule of

The New Republic

penned the influential tract “A Planned Society.” Stuart Chase penned another called “A New Deal.” Before long, Roosevelt was awash in new ideas. With the new tools from 1913 in his hands, Roosevelt had the ability to turn screws and tighten values throughout the economy. How could he resist?

Among the ideas adopted was one pushed forward by a California physician named Francis Townsend in 1933. The Townsend Plan was designed to extinguish poverty forever. When it first hit the presses, Roosevelt was opposed. But its popularity caught on; two years later under pressure from the voters, Roosevelt introduced the Social Security Act. The organizers of the Townsend Plan became major critics of the government program, complaining that it did not provide enough assistance.

Following the establishment of the act’s primary benefit, the old age insurance provision, Congress amended the law four years later to add survivors’ insurance. Medicare benefits were added in 1965. By 2005, Social Security and Medicare took up 27 percent of the federal budget. While the program was relatively young, it was a novel idea and controversy surrounded the question of whether the program paid out enough based on the required payroll deductions people paid in. Little concern was given to whether it could remain solvent in the long term.

Other programs introduced as part of the original act included the Federal Unemployment Insurance Act (FUTA), funded by a tax on employers’ side of payroll; and Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), now called Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Social Security and its related legislation have expanded broadly beyond the biggest pieces, old age insurance and Medicare. The Act began institutionalization of a dual-track system, providing both old age insurance and related benefits, and the other designed to work with the states in a dollar-matching program for a vast network. Today, the overall program includes national minimum wage and child labor laws; federal disability insurance; Medicaid; public housing and rent entitlements; food stamps; and means-tested income assistance for the elderly and disabled. All these programs—outgrowths of Social Security—have expanded today to represent a large, complex, and expensive system of what the Romans called

panem et circensis

—bread and circuses (see

Figure 6.1

).

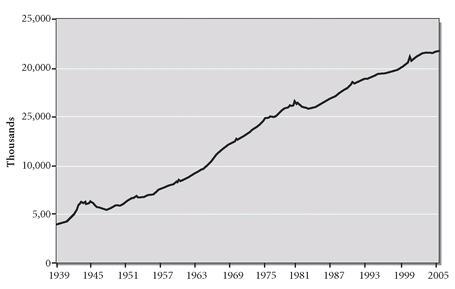

Figure 6.1

Government Employment, 1939-2005

The government programs created in the 1930s have required an ever-increasing bureaucracy. All of these programs—outgrowths of Social Security—have expanded today to represent a large, complex, and expensive system of what the Romans called panemet circensis—bread and circuses.

Source:

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That the government should take responsibility for the needy, poor, and disabled is not a new idea at all.The Elizabethan Poor Laws were enacted in England in 1597.The individual duty to provide the “seven corporal works of mercy” predates the modern era. These seven were to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked, visit the sick, visit the prisoner, and bury the dead. What is new is the idea that the state should serve as the primary caregiver.

The Elizabethan Poor Laws were based on the premise that the family was primarily responsible for providing help to anyone in need, especially within their own families. Elderly parents were to be cared for by younger family members. Beyond that, the churches were responsible for providing relief. In fact, the community parish was the basic unit of responsibility under the Elizabethan Poor Law system. By 1601, inconsistencies in the administration of relief, the growing problem of burglars and robbers—the “sturdy beggars” of the times—and the difficulty of dealing with those who took advantage of the system led to a consolidation of these poor laws.

The Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.”

14

While broad, the intent of this amendment is clear: The federal government of the old republic had never been intended to watch over the welfare of its citizens. Yet, the feds now administer more welfare programs than we can imagine. Remembering their names is like learning the logarithmic tables by heart—just as difficult and even more pointless. State programs, while they exist, are often only supplementary. In many instances, funding of state programs is derived from handouts determined and administered by the federal government, invariably with strings attached.

The robust mob of organizations, designed to provide jobs, training, and more, is mind-boggling. These groups included the Civil Works Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the National Youth Administration, and the Works Progress Administration—all agencies of the federal government, all intended to provide services that “are reserved to the states respectively” as identified in the Tenth Amendment.

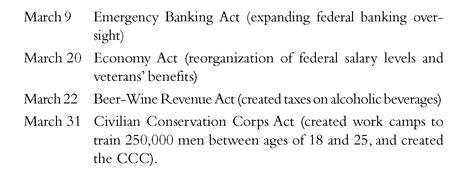

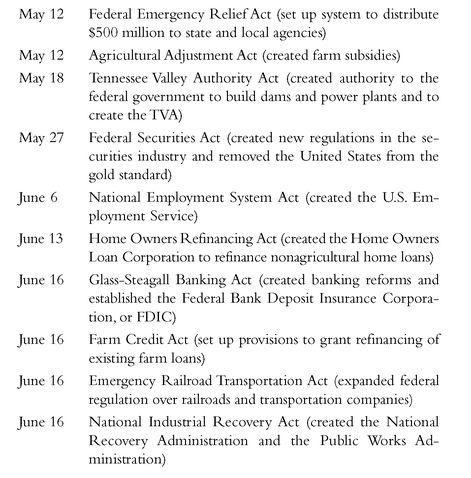

The largest volume of legislation, however, was passed during the first congressional session, known as the “Hundred Days” (from March 9 to June 16, 1933):

By the time the New Deal legislation had passed into law, a rift developed between President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court. In 1935, the justices—a majority of whom had been appointed by stodgy old Republican presidents—declared much of the New Deal agenda unconstitutional. That year, the Court threw out the Railroad Retirement Act of 1934, a law that had set up pension plans for railway workers. It also threw out one of the most significant pieces of the New Deal, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. In 1936, the trend continued when the Court declared the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court was intended to have the last word for the judiciary branch. It was expected to be made up of wise old men, like a council of elders in more primitive societies. At the time, six of the nine judges were over 70.They were not dead, but they were old enough to know better than to go along with the president’s ambitious new programs. Early in 1937, Roosevelt spoke with his advisors about a new draft bill that called for Supreme Court justices to retire at the age of 70. Under the proposed new rule, if they did not retire, the president would be able to appoint a new judge, increasing the number of justices on the Court to 15.

Roosevelt appealed directly to the masses during a Fireside Chat in March 1937. He explained his proposed new legislation and defined both the new imperial executive and its contempt for the wisdom of old age:

The American people have learned from the depression. For in the last three national elections an overwhelming majority of them have voted a mandate that the Congress and the president begin the task of providing . . . protection [aka something for nothing]—not after long years of debate, but now.The courts, however, have cast doubts on the ability of the elected Congress to protect us against catastrophe by meeting squarely our modern social and economic conditions . . . . [S]ince the rise of the modern movement for social and economic progress through legislation, the court has more and more often and more and more boldly asserted a power to veto laws passed by the Congress and by state legislatures . . . .The court in addition to the proper use of its judicial functions has improperly set itself up as a third house of the Congress—a super-legislature, as one of the justices has called it—reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there, and which were never intended to be there.

What is my proposal? It is simply this: Whenever a judge or justice of any federal court has reached the age of 70 and does not avail himself of the opportunity to retire on a pension, a new member shall be appointed by the president then in office, with the approval, as required by the Constitution, of the Senate of the United States.

15

While retirement would not be mandatory as soon as a judge turned 70, the outcome of this proposal is apparent. As soon as a judge did reach that age, the president would certainly appoint a new member. The United States would have ended up with a younger, more obliging Court with a permanent membership of 15. Those bringing appeals forward to the Court would time their filings based on current age, time to age 70, and the president then in office. Even Roosevelt admitted this in a veiled threat to the Court, in the same address. He said “The number of judges to be appointed would depend wholly on the decision of present judges now over 70, or those who would subsequently reach the age of 70.”

16

Congress balked. After months of hearings on the bill, the Senate killed FDR’s plan with a 70 to 20 vote.The proposal was sent back to committee and nothing came of it.

But the winds of empire continued to blow hard. Economists, philosophers, radicals, and other malcontents rolled into Washington like tumble-weeds, with plans for centralized control of the economy.

When Roosevelt entered office, having chided the Republicans before him for spending too much money, the federal debt, after 143 years, had grown to $19 billion. Roosevelt—in just four years—borrowed almost as much money as all the dead presidents who came before him. He and members of Congress at the time were disturbed about it, but ideas arise as they are needed.The big spenders needed an idea that would permit huge new levels of government debt.They soon found it:

A government, unlike an individual, can borrow and spend indefinitely without fear of bankruptcy.

A government borrows money from its citizens. Therefore, it owes that debt to its citizens. The debt is therefore owed by the people to themselves. And no matter how large the debt gets, the financial impact on the citizens and the government is negligible. On the subject of what would happen if that debt were owed to foreign bond holders, the Roosevelt era empire builders were less clear.