The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (36 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

But dead men don’t talk, and the unborn don’t vote. Politicians in America—just as those in Britain, Italy, and Germany—gradually came to see that they could get the benefits of spending money in the present, while passing on the debts to the next administration and the next generation. Then, as now, war provided cover for excess spending. First, there were the debts from the American Revolution, which were paid down quickly. Then came the War of 1812, Mexican War, and the War between the States. Each time, spending was increased, debts were taken on, and then, after the war, the debt was paid down, or paid off completely.

World War I saw federal debt explode from $3 billion to $26 billion. Presidents Harding and Hoover paid it down to $16 billion. But then came the Great Depression, Roosevelt, and World War II. By 1945, federal debt had reached $260 billion.Then came something new. The war did not end. It continued as the Cold War, and instead of the debt being paid down, it was increased.

Under Ronald Reagan, America’s debt seemed on course for Mars. Less than $1 trillion in 1980, it soared to $2.7 trillion before Reagan left office. One might have expected some relief after the Cold War was over. But the habit of debt is hard to break. By the time George W. Bush took office, the debt had risen to $5.7 trillion.

Mr. Bush, a conservative, might have seized the opportunity to pay down the debt. The nation was at peace and expected huge budget surpluses. He promised as much when he stood before a joint session of Congress in 2001 and announced his budget.

“That night,” Paul O’Neill tells us in the book by Ron Suskind,

The Price of Loyalty,

“Bush stood before the nation and said something that knowledgeable people in the U.S. government knew to be false.”

4

Generations of Republicans had promised balanced budgets. Only war had permitted them to continue running up debt.With no war, the Republicans squirmed. But since 1917, wars had always seemed to come along just when they were needed, and now they included a remarkable event: 9/11. All of a sudden, another strange war was announced against an enemy no one could find on a map—a

War on Terror.

Now, the war, the spending, and the debts could go on forever.

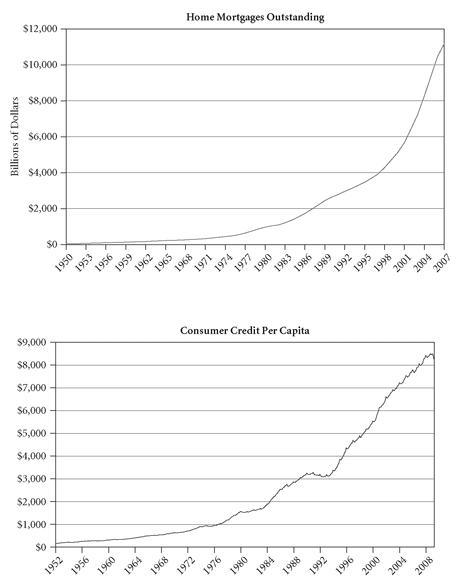

Figure 10.3

Home Mortgages Outstanding, U.S. Consumer Credit per Capita, and Average U.S. Credit Card Debt per Houshold

Sources:

Federal Reserve;

CardTrack.com

.

In the following 24 months, the Bush administration added more debt faster than at any time in the first 200 years of the nation’s existence.

MAESTRO’S PERFORMANCE

In February 2005, Alan Greenspan gave a speech in honor of the first modern economist—Adam Smith. The Fed chairman journeyed to Fife College, in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland, where Smith was born in 1723. There, he commented on Smith’s work: “Most of Smith’s free market paradigm remains applicable to this day,” said he.

5

In particular, the world seems to have discovered that independent buyers and sellers are better at delivering the goods than government planners.

This would have come as a shock to George Orwell. Writing at the beginning of World War II, Orwell expressed the belief of millions: “I began this book to the tune of German bombs . . . . What this war has demonstrated is that private capitalism—that is, an economic system in which land, factories, mines and transports are owned privately and operated solely for profit—does not work. It cannot deliver the goods.”

6

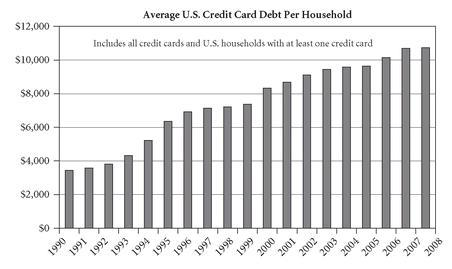

Figure 10.4

Individual Loans at Commercial Banks and Commercial and Industrial Loans at All Commercial Banks

As the empire matured, Americans embraced new ideas and attitudes. People switched their attention from assets to cash f low, from balance sheets to monthly statements, from building long-term wealth to paycheck-to-paycheck financing, from saving to spending, and from “just in case” to “just in time.”

Source:

Federal Reserve.

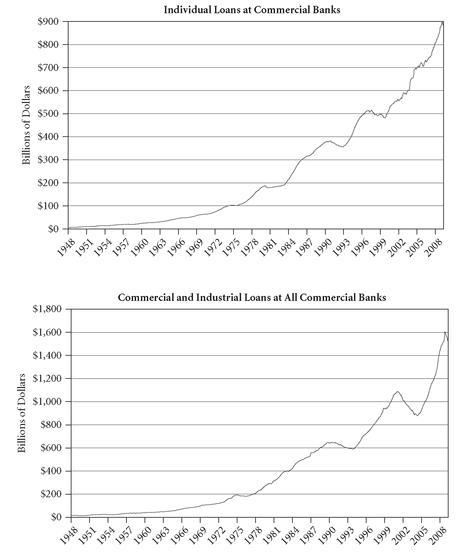

Figure 10.5

Real Estate Loans at All Commercial Banks and U.S. Corporate Debt

Source:

Federal Reserve.

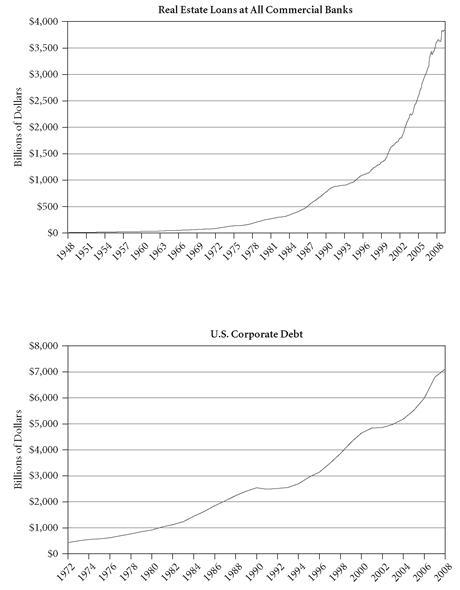

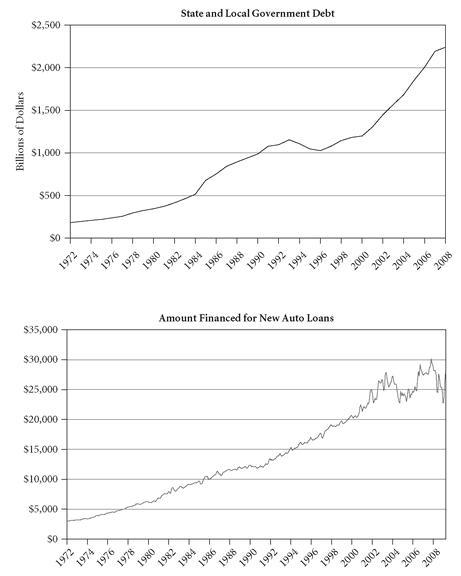

Figure 10.6

State and Local Government Debt and Amount Financed for New Auto Loans

Consistent with speculative bubbles throughout history, the great Tech Wreck on Wall Street circa AD 2000—which was itself financed by corporate borrowing—was followed by a dramatic rise in speculation on real estate . . . also, on a borrowed dime.

Source:

Federal Reserve.

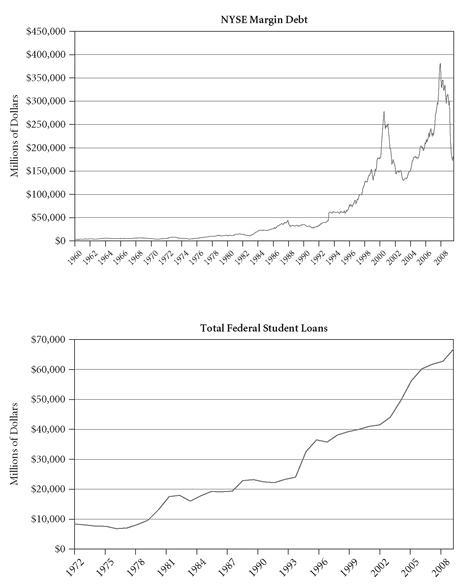

Figure 10.7

NYSE Margin Debt and Total Federal Student Loans

Sources:

New York Stock Exchange and The College Board.

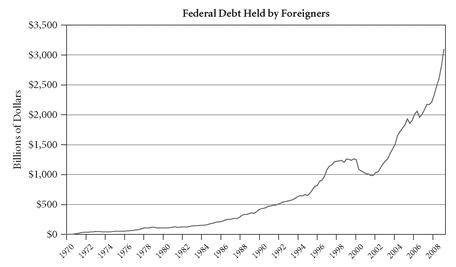

Figure 10.8

Federal Debt Held by Foreigners

As the gusts of credit, debt, borrowing, and spending blew across the nation, very few of the old attitudes and institutions were left standing. By the early twenty-first century, Americans borrowed money for everything they wanted: They borrowed to go to school, to drive in late model SUVs, to finance new football stadiums, and to convert aging industrial districts into shopping meccas. How was all this borrowing made possible? It was made possible by the kindness of strangers.

Source:

Federal Reserve.

Orwell was wrong. Capitalism delivered the goods better than socialism, a fact that even nearsighted journalists and central bankers were eventually able to see. But even after the fall of the Berlin Wall, continued America’s most celebrated central banker, there was “no eulogy for central planning.”

Adam Smith had proposed a useful metaphor to help explain how a system of private, individual decision making—which must have looked chaotic to a top-down observer—actually functioned to the betterment of all. A rise in the price of pigs, for example, sends a signal to the hog raisers to produce more. Thus, the market is guided by an “invisible hand” to produce exactly as much of a thing as people really want and can really afford.

Quick-witted readers will already be gurgling with indignation. Markets work best without the heavy hand of regulation, Greenspan acknowledged. But he seemed to exempt, conveniently, the credit markets. The maestro’s speech hit a false note; rather like President Bush’s approach to evangelical democracy, it seemed to miss the point. Instead of letting lenders of credit and demanders of it be guided by an “invisible hand,” for years the Fed chief ’s boney paws have drawn them together. Mr. Greenspan’s “Open Market Committee,” not the open market, has largely determined the rate at which lenders will lend, short term, and at which borrowers will borrow.

Why is it that what is good for the goose of lumber markets, stock markets, grain markets, laptop computer markets, and almost every other market under Heaven is not good enough for the gander of the credit market? The answer is not one of logic, but of convenience. Most of the time, political leaders prefer easier credit terms than buyers and sellers would determine on their own. In setting its key rate, the Open Market Committee is likely to set a rate that is to the politicians’ liking.