The New Penguin History of the World (115 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

In effect, the effort which began with the conquest of Hungary had been the last heave of a long-troubled power. Their army was no longer abreast of the latest military technology: it lacked the field artillery which had become the decisive weapon of the seventeenth-century battlefield. At sea, the Turks clung to the old galley tactics of ramming and boarding and were less and less successful against the Atlantic nations’ technique of using the ship as a floating artillery battery (unfortunately for themselves, the Venetians were conservative too). Turkish power was in any case badly overstretched. It had saved Protestantism in Germany, Hungary and Transylvania, but it was pinned down in Asia (where the conquest of Iraq from Persia in 1639 brought almost the whole Arab-Islamic world under Ottoman rule) as well as in Europe and Africa, and the strain was too much for a structure allowed to relax by inadequate or incompetent rulers. A great vizier had pulled things together in the middle of the century to make the last offensives possible. But there were weaknesses which he could not correct, for they were inherent in the nature of the empire itself.

More a military occupation for purposes of plunder than a political unity, the Ottoman empire was geared to continual expansion and the gathering of new resources in taxes and manpower. Moreover, it was dangerously dependent on subjects whose loyalty it could not win. The Ottomans usually respected the customs and institutions of non-Muslim communities, which were ruled under the

millet

system, through their own authorities. The Greek Orthodox, Armenians and Jews were the most important and each had their own arrangements, the Greek Christians having to pay a special poll-tax, for example, and being ruled, ultimately, by their own patriarch in Constantinople. At lower levels, such arrangements as seemed best were made with leaders of local communities for the

support of the plunder machine. In the end this bred over-mighty subjects as pashas feathered their own nests amid incoherence and inefficiency. It gave the subjects of the sultan no sense of identification with his rule but, rather, alienated them from it.

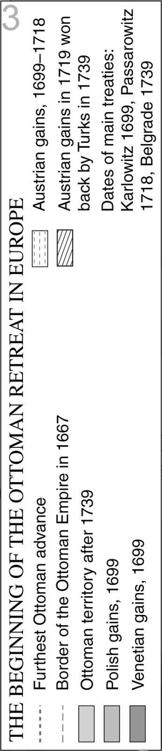

The year 1683, therefore, although a good symbolic date as the last time that Europe stood upon the defensive against Islam before going over to the attack, was a less dangerous moment than it looked. Afterwards the tide of Turkish power was to ebb almost without interruption until in 1918 it was once more confined to the immediate hinterland of Constantinople and the old Ottoman heartland, Anatolia. The relief of Vienna by the King of Poland, John Sobieski, was followed by the liberation of Hungary after a century and a half of Ottoman rule. The dethronement of an unsuccessful sultan in 1687 and his incarceration in a cage proved no cure for Turkish weakness. In 1699 Hungary formally became part of the Habsburg dominions, after the first peace the Ottomans signed as a defeated power. In the following century Transylvania, the Bukovina, and most of the Black Sea coasts would follow it out of Ottoman control. By 1800, the Russians had asserted a special protection over the Christian subjects of the Ottomans and had already tried promoting rebellion among them. In the eighteenth century, too, Ottoman rule ebbed in Africa and Asia; by the end of it, though forms might be preserved, the Ottoman caliphate was somewhat like that of the Abbasids in their declining days. Morocco, Algeria, Tunis, Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia and Arabia were all in varying degrees independent or semi-independent.

It was not the traditional guardians of eastern Europe, the once-great Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth and the Habsburgs, who were the legatees of the Ottoman heritage, nor they who inflicted the most punishing blows as the Ottoman empire crumbled. The Poles were in fact nearing the end of their own history as an independent nation. The personal union of Lithuania and Poland had been turned into a real union of the two countries too late. In 1572, when the last king of the Jagiellon line died without an heir, the throne had become not only theoretically but actually elective. A huge area was up for grabs. His successor was French and for the next century Polish magnates and foreign kings disputed each election, while their country was under grave and continuing pressure from Turks, Russians and Swedes. Poland prospered against these enemies only when they were embarrassed elsewhere. The Swedes descended on her northern territories during the Thirty Years’ War and the last of the Polish coast was given up to them in 1660. Internal divisions had worsened, too; the Counter-Reformation brought religious persecution to the Polish Protestants and there were risings of Cossacks in the Ukraine and continuing serf revolts.

The election as king of the heroic John Sobieski was the last which was not the outcome of machinations by foreign rulers. He had won important victories and managed to preside over Poland’s curious and highly decentralized constitution. The elected kings had very little legal power to balance that of the landowners. They had no standing army and could rely only on their own personal troops when factions among the gentry

or magnates fell back on the practice of armed rebellion (‘confederation’) to obtain their wishes. In the Diet, the central parliamentary body of the kingdom, a rule of unanimity stood in the way of any reform. Yet reform was badly needed, if a geographically ill-defined, religiously divided Poland, ruled by a narrowly selfish rural gentry, was to survive. Poland was a medieval community in a modernizing world.

John Sobieski could do nothing to change this. Poland’s social structure was strongly resistant to reform. The nobility or gentry were effectively the clients of a few great families of extraordinary wealth. One clan, the Radziwills, owned estates half the size of Ireland and held a court which outshone that of Warsaw; the Potocki estates covered 6,500 square miles (roughly half the area of the Dutch Republic). The smaller landowners could not stand up to such grandees. Their estates made up less than a tenth of Poland in 1700. The million or so gentry who were legally the Polish ‘nation’ were for the most part poor, and therefore dominated by great magnates reluctant to surrender their power to arrange a confederation or manipulate a Diet. At the bottom of the pile were the peasants, some of the most miserable in Europe, in 1700 unendingly battling the feudal dues demanded of them, over whom landlords still had rights of life and death. The towns were powerless. Their total population was only half the size of the gentry and they had been devastated by the seventeenth-century wars. Yet Prussia and Russia also rested on backward agrarian and feudal infrastructures and survived. Poland was the only one of the three eastern states to go under completely. The principle of election blocked the emergence of Polish Tudors or Bourbons who could identify their own dynastic instincts of self-aggrandizement with those of the nation. Poland entered the eighteenth century under a foreign king, the Elector of Saxony, who was chosen to succeed John Sobieski in 1697, soon deposed by the Swedes, and then put back again on his throne by the Russians.

Russia was the coming new great power in the east. Her national identity had been barely discernible in 1500. Two hundred years later her potential was still only beginning to dawn on most western statesmen, though the Poles and Swedes were already alive to it. It now requires an effort to realize how rapid and astonishing was the appearance as a major force of what was to become one of the two most powerful states in the world. At the beginning of the European age, when only the ground-plan of the Russian future had been laid out by Ivan the Great, such an outcome was inconceivable, and so it long remained. The first man formally to bear the title of ‘Tsar’ was his grandson Ivan IV, crowned in 1547; and the conferment of the title at his coronation was meant to say that the Grand Prince of Muscovy had become an emperor ruling many peoples. In spite of a

ferocious vigour which earned him his nickname ‘the Terrible’, he played no significant role in European affairs. So little was Russia known, even in the next century, that a French king could write to a Tsar, not knowing that the prince whom he addressed had been dead for ten years. The shape of a future Russia was determined slowly, and almost unnoticed in the West. Even after Ivan the Great, Russia had remained territorially ill-defined and exposed. The Turks had pushed into south-east Europe. Between them and Muscovy lay the Ukraine, the lands of the Cossacks, peoples who fiercely protected their independence. So long as they had no powerful neighbours, they found it easy to do so. To the east of Russia, the Urals provided a theoretical though hardly a realistic frontier. Russia’s rulers have always found it easy to feel isolated in the middle of hostile space. Almost instinctively, they have sought natural frontiers at its edges or a protective glacis of clients.

The first steps had to be the consolidation of the gains of Ivan the Great which constituted the Russian heartland. Then came penetration of the wilderness of the north. When Ivan the Terrible came to the throne, Russia had a small Baltic coast and a vast territory stretching up to the White Sea, thinly inhabited by scattered and primitive peoples, but providing a route to the west; in 1584 the port of Archangel was founded. Ivan could do little on the Baltic front but successfully turned on the Tatars after they burned Moscow yet again in 1571, allegedly slaughtering 150,000 in the process. He drove them from Kazan and Astrakhan and won control of the whole length of the Volga, carrying Muscovite power to the Caspian.

The other great thrust which began in his reign was across the Urals, into Siberia, and was to be less one of conquest than of settlement. Even today, most of the Russian republic is in Asia, and for nearly two centuries a world power was ruled by the Tsars and their successors. The first steps towards this outcome were an ironic anticipation of what was to be a theme of the major Siberian frontier in later times: the first Russian settlers across the Urals seem to have been political refugees from Novgorod. Among those who followed were others fleeing from serfdom (there were no serfs in Siberia) and aggrieved Cossacks. By 1600 there were Russian settlements as much as six hundred miles beyond the Urals, closely supervised by a competent bureaucracy out to assure the state tribute in furs. The rivers were the keys to the region, more important even than those of the American frontier. Within fifty years a man and his goods could travel by river with only three portages from Tobolsk, 300 miles east of the Urals, to the port of Okhotsk, 3000 miles away. There he would be only 400 miles by sea from Sakhalin, the northernmost of the major islands of the chain which makes up Japan – a sea-passage about as long as that

from Land’s End to Antwerp. By 1700 there were 200,000 settlers east of the Urals: it had by then been possible to agree the treaty of Nerchinsk with the Chinese, and some Russians, we are told, talked of the conquest of China.