The New Penguin History of the World (169 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Unfortunately, the principle of nationality could not always be applied. Geographical, historical, cultural and economic realities cut across it. When it prevailed over them – as in the destruction of the Danube’s economic unity – the results could be bad; when it did not they could be just as bad because of the aggrieved feelings left behind. Eastern and central Europe was studded with national minorities embedded resentfully in nations to which they felt no allegiance. A third of Poland’s population did not speak

Polish; more than a third of Czechoslovakia’s consisted of minorities of Poles, Russians, Germans, Magyars and Ruthenes; an enlarged Romania now contained over a million Magyars. In some places, the infringement of the principle was felt with especial acuteness as an injustice. Germans resented the existence of a ‘corridor’ connecting Poland with the sea across German lands, Italy was disappointed of Adriatic spoils held out to her by her allies when they had needed her help, and the Irish had still not got Home Rule after all.

The most obvious non-European question concerned the disposition of the German colonies. Here there was an important innovation. Undisguised colonial greed was not acceptable to the United States; instead, tutelage for non-European peoples, formerly under German or Turkish rule, was provided by the device of trusteeship. ‘Mandates’ were given to the victorious powers (though the United States declined any) by a new ‘League of Nations’ to administer these territories while they were prepared for self-government; it was the most imaginative idea to emerge from the settlement, even though it was used to drape with respectability the last major conquests of European imperialism.

The League of Nations owed much to the enthusiasm of the American president, Woodrow Wilson, who ensured its Covenant – its constitution – pride of place as the first part of the Peace Treaty. It was the one instance in which the settlement transcended the idea of nationalism (even the British empire had been represented as individual units, one of which, significantly, was India). It also transcended that of Europe; it is another sign of the new era that twenty-six of the original forty-two members of the League were countries outside Europe. Unfortunately, because of domestic politics Wilson had not taken into account, the United States was not among them. This was the most fatal of several grave weaknesses which made it impossible for the League to satisfy the expectations it had aroused. Perhaps these were all unrealizable in principle, given the actual state of world political forces. None the less, the League was to have its successes in handling matters which might, without its intervention, have proved dangerous. If exaggerated hopes had been entertained that it might do more, it does not mean it was not a practical as well as a great and imaginative idea.

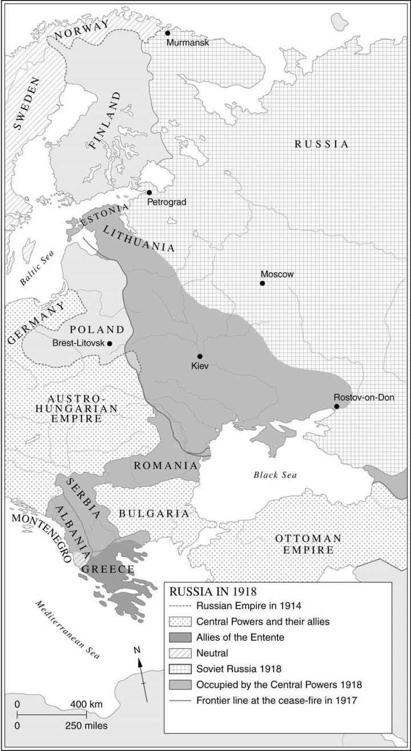

Russia was absent from the League just as she was from the peace conference. Probably the latter was the more important. The political arrangements to shape the next stage of European history were entered into without consulting her, though in eastern Europe this meant the drawing of boundaries in which any Russian government was bound to be vitally interested. It was true that the Bolshevik leaders did all they could to

provide excuses for excluding them. They envenomed relations with the major powers by revolutionary propaganda, for they were convinced that the capitalist countries were determined to overthrow them. The British prime minister, Lloyd George, and Wilson were in fact more flexible – even sympathetic – than many of their colleagues and electors in dealing with Russia. Their French colleague, Clemenceau, on the other hand, was passionately anti-Bolshevik and had the support of many French ex-soldiers and investors in being so; Versailles was the first great European peace to be made by powers all the time aware of the dangers of disappointing democratic electorates. But however the responsibility is allocated, the outcome was that Russia, the European power which had, potentially, the greatest weight of all in the affairs of the continent, was not consulted in the making of a new Europe. Though for the time being virtually out of action, it was bound eventually to join the ranks of those who wished to revise the settlement or overthrow it. It only made it worse that it rulers detested the social system it was meant to protect.

Huge hopes had been entertained of this settlement. They were often unrealistic, yet in spite of its manifest failures, the peace has been over-condemned, for it had many good points. When it failed, it was for reasons which were for the most part beyond the control of the men who made it. In the first place, the days of a European world hegemony in the narrow political sense were over. The peace treaties of 1919 could do little to secure the future beyond Europe. The old imperial policemen were now too weakened to do their job inside Europe, let alone outside; some had disappeared altogether. In the end the United States had been needed to ensure Germany’s defeat but now she plunged into a period of artificial isolation. Nor did Russia wish to be involved in the continent’s stabilizing. The isolationism of the one power and the sterilization of the other by ideology left Europe to its own inadequate devices. When no revolution broke out in Europe, the Russians turned in on themselves; when Americans were given the chance by Wilson to be involved in Europe’s peacekeeping, they refused it. Both decisions are comprehensible, but their combined effect was to preserve an illusion of European autonomy which was no longer a reality and could no longer be an adequate framework for handling its problems. Finally, the settlement’s gravest immediate weakness lay in the economic fragility of the new structures it presupposed. Here its terms were more in question: self-determination often made nonsense of economics. But it is difficult to see on what grounds self-determination could have been set aside. Ireland’s problems are still with us eighty years after an independent Irish Free State appeared in 1922.

The situation was all the more likely to prove unstable because many

illusions persisted in Europe and many new ones arose. Allied victory and the rhetoric of peace-making made many think that there had been a great triumph of liberalism and democracy. Four autocratic anti-national illiberal empires had collapsed, after all, and to this day the peace settlement retains the distinction of being the only one in history made by great powers all of which were democracies. Liberal optimism also drew strength from the ostentatious stance taken by Wilson during the war; he had done all he could to make it clear that he saw the participation of the United States as essentially different in kind from that of the other Allies, being governed (he reiterated) by high-minded ideals and a belief that the world could be made safe for democracy if other nations would give up their bad old ways. Some thought that he had been shown to be right; the new states, above all the new Germany, adopted liberal, parliamentary constitutions and often republican ones, too. Finally, there was the illusion of the League; the dream of a new international authority, which was not an empire, seemed at last a reality.

Yet all this was rooted in fallacy and false premise. Since the peacemakers had been obliged to do much more than enthrone liberal principles – they had also to pay debts, protect vested interests, and take account of intractable facts – those principles had been much muddied in practice. Above all, they had left much unsatisfied nationalism about and had created new and fierce nationalist resentments in Germany. Perhaps this could not be helped, but it was a soil in which things other than liberalism could grow. Further, the democratic institutions of the new states – and the old ones, too, for that matter – were being launched on a world whose economic structure was terribly damaged. Everywhere, poverty, hardship and unemployment exacerbated political struggle and in many places they were made worse by the special dislocations produced by respect for national sovereignty. The crumbling of old economic patterns of exchange in the war made it much more difficult to deal with problems like peasant poverty and unemployment, too; Russia, once the granary of much of western Europe, was now inaccessible economically. This was a background which revolutionaries could exploit. The communists were happy and ready to do this, for they believed that history had cast them for this role, and soon their efforts were reinforced in some countries by another radical phenomenon, fascism.

Communism threatened the new Europe in two ways. Internally, each country soon had a revolutionary communist party. They effected little that was positive, but caused great alarm. They also did much to prevent the emergence of strong progressive parties. This was because of the circumstances of their birth. A ‘Comintern’, or Third International, was

devised by the Russians in March 1919 to provide leadership for the international socialist movement, which might otherwise, they feared, rally again to the old leaders, whose lack of revolutionary zeal they blamed for a failure to exploit the opportunities of the war. The test of socialist movements for Lenin was adherence to the Comintern, whose principles were deliberately rigid, disciplined and uncompromising, in accordance with his view of the needs of an effective revolutionary party. In almost every country this divided socialists into two camps. Some adhered to the Comintern and took the name communist; others, though sometimes claiming still to be Marxists, remained in the rump national parties and movements. They competed for working-class support and fought one another bitterly.

The new revolutionary threat on the Left was all the more alarming to many Europeans because there were so many revolutionary possibilities for communists to exploit. The most conspicuous led to the installation of a Bolshevik government in Hungary, but more startling, perhaps, were attempted communist coups in Germany, some briefly successful. The German situation was especially ironical, for the government of the new republic which emerged there in the aftermath of defeat was dominated by socialists, who were forced back to reliance upon conservative forces – notably the professional soldiers of the old army – in order to prevent revolution. This happened even before the founding of the Comintern and it gave a special bitterness to the divisions of the Left in Germany. But everywhere, communist policy made united resistance to conservatism more difficult, frightening moderates with revolutionary rhetoric and conspiracy.

In eastern Europe, the social threat was often seen also as a Russian threat. The Comintern was manipulated as an instrument of Soviet foreign policy by the Bolshevik leaders; this was justifiable, given their assumption that the future of world revolution depended upon the preservation of the first socialist state as a citadel of the international working class. In the early years of civil war and slow consolidation of Bolshevik power in Russia that belief led to the deliberate incitement of disaffection abroad in order to preoccupy capitalist governments. But in eastern and central Europe there was more to it than this, because the actual territorial settlement of that area was in doubt long after the Versailles treaty. The First World War did not end there until in March 1921 a peace treaty between Russia and the new Polish Republic provided frontiers lasting until 1939. Poland was the most anti-Russian by tradition, the most anti-Bolshevik by religion, as well as the largest and most ambitious of the new nations. But all of them felt threatened by a recovery of Russian power, especially now that it was tied up with the threat of social revolution. This connection helped to turn many of these states before 1939 to dictatorial or military governments which would at least guarantee a strong anti-communist line.

Fear of communist revolution in eastern and central Europe was most evident in the immediate post-war years, when economic collapse and uncertainty about the outcome of the Polish–Russian war (which, at one time, appeared to threaten Warsaw itself) provided the background. In 1921, with peace at last and, symbolically, the establishment of orderly official relations between the USSR and Great Britain, there was a noticeable relaxation. This was connected with the Russian government’s own sense of emerging from a period of acute danger in the civil war. It did not produce much in the way of better diplomatic manners, and revolutionary propaganda and denunciation of capitalist countries did not cease, but the Bolsheviks could now turn to the rebuilding of their own shattered land. In 1921 Russian pig-iron production was about one-fifth of its 1913 level, that of coal a tiny 3 per cent or so, while the railways had less than half as many locomotives in service as at the start of the war. Livestock had declined by over a quarter and cereal deliveries were less than two-fifths of those of 1916. On to this impoverished economy there fell in 1921 a drought in south Russia. More than two million died in the subsequent famine and even cannibalism was reported.

Liberalization of the economy brought about a turnround. By 1927 both industrial and agricultural production were nearly back to pre-war levels. The regime in these years was undergoing great uncertainty in its leadership. This had already been apparent before Lenin died in 1924, but the removal of a man whose acknowledged ascendancy had kept forces within it in balance opened a period of evolution and debate in the Bolshevik leadership. It was not about the centralized, autocratic nature of the regime which had emerged from the 1917 revolution, for none of the protagonists considered that political liberation was conceivable or that the use of secret police and the party’s dictatorship could be dispensed with in a world of hostile capitalist states. But they could disagree about economic policy and tactics and personal rivalry sometimes gave extra edge to this.