The New Penguin History of the World (200 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

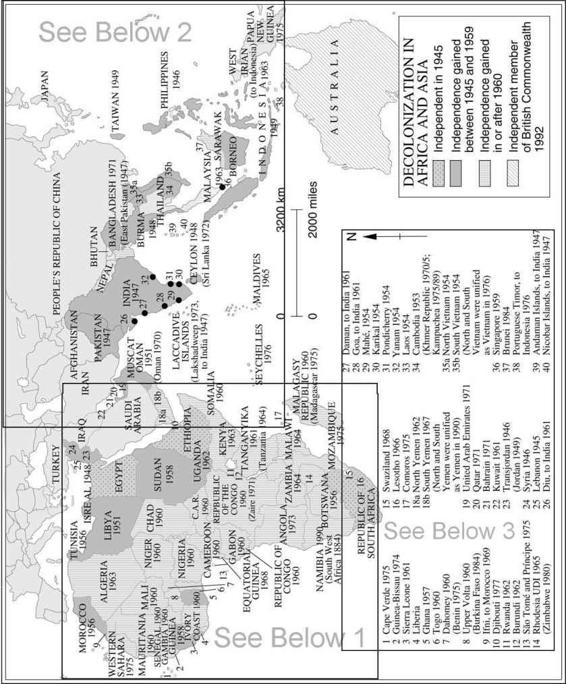

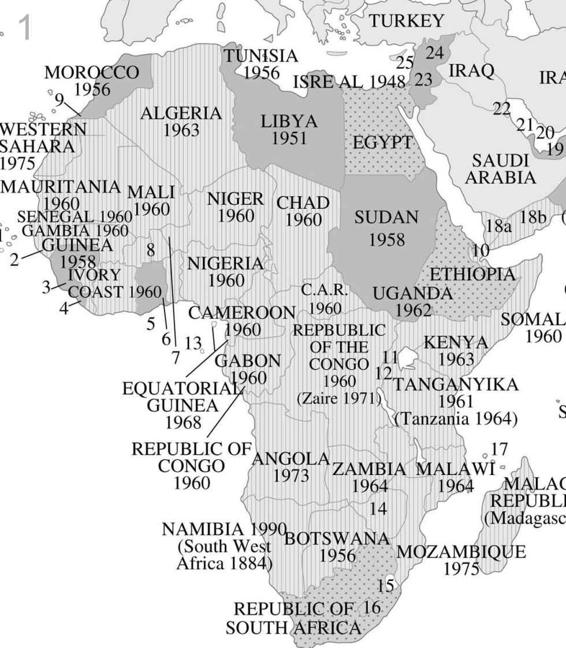

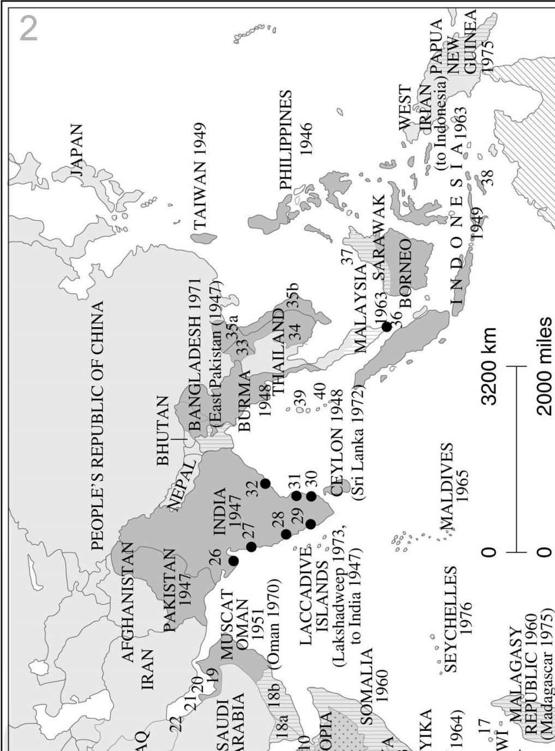

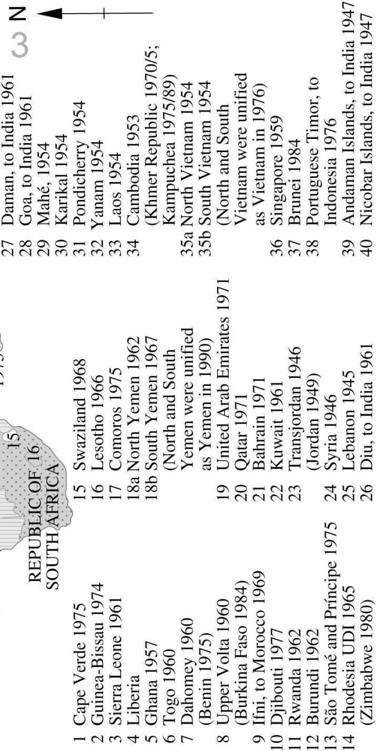

The outcome was a black Africa that owes its present form in the main to decisions of nineteenth-century Europeans (just as much of the Middle East owes its political framework to the Europeans in the twentieth century). New African ‘nations’ were usually defined by the boundaries of former colonies and those boundaries have proved remarkably enduring. They often enclosed peoples of many languages, stocks and customs, over whom colonial administrations had provided little more than a formal unity. As Africa lacked the unifying influence of great indigenous civilizations, such as those of Asia, to offset the colonial fragmentation of the continent, imperial withdrawal was followed by its Balkanization. The doctrine of nationalism that appealed to the westernized African élites (Senegal, a Muslim country, had a president who wrote poetry in French and was an expert on Goethe) confirmed a continent’s fragmentation, often ignoring important realities, which colonialism had contained or manipulated. The sometimes strident nationalist rhetoric of new rulers was often a response to the dangers of centrifugal forces. West Africans combed the historical record – such as it was – of ancient Mali and Ghana, and East Africans brooded over the past that might be hidden in relics, such as the ruins of Zimbabwe, in order to forge national mythologies like those of earlier nation-makers in Europe. Nationalism was as much the product of decolonization in black Africa as the cause.

New internal divisions were not Africa’s only or its worst problems. In spite of the continent’s great economic potential, the economic and social foundations for a prosperous future were shaky. Once again, the imperial legacy mattered supremely. Colonial regimes in Africa left behind feebler cultural and economic infrastructures than in Asia. Rates of literacy were low and trained cadres of administrators and technical experts were small. Africa’s important economic resources (especially in minerals) required skills, capital and marketing facilities for their exploitation, which could only come in the near future from the world outside (and white South Africa long counted as ‘outside’ to many black politicians). What was more, some African economies had recently undergone particular disruption and diversion because of European needs and in European interests. During the war of 1939–45, agriculture in some of the British colonies had shifted towards the growing of cash crops on a large scale for export. Whether this was or was not in the long-term interests of peasants who had previously raised crops and livestock only for their own consumption is debatable, but what is certain is that the immediate consequences were rapid and profound. One was an inflow of cash in payment for produce the British and Americans needed. Some of this came through in higher wages, but the spread of a cash economy often had disturbing local effects. Unanticipated urban growth and regional development took place. Many African countries were thus tied to patterns of development that were soon to show their vulnerabilities and limitations in the post-war world. Even the benevolent intentions of a programme like the British Colonial Development and Welfare Fund, or many international aid programmes, objectively helped to shackle African producers to a world market. Such handicaps were the more grievous when they were compounded, as was often the case, by mistaken economic policy after independence. A drive for industrialization through import-substitution often led to disastrous agrarian consequences as the prices of cash crops were kept artificially low in relation to those of locally manufactured goods. Almost always, farmers were sacrificed to townspeople and low prices left them with no incentive to raise production. Given that populations had begun to rise in the 1930s and did so even more rapidly after 1960, discontent was inevitable as

disappointment with the reality of ‘freedom’ from the colonial powers set in.

Nonetheless, in spite of its difficulties, the process of decolonization in black Africa was hardly interrupted. In 1945 the only truly independent countries in Africa other than Egypt had been Ethiopia (which had itself, from 1935 to 1943, been briefly under colonial rule) and Liberia, though in reality and law the Union of South Africa was a self-governing Dominion of the British Commonwealth and is therefore only formally excluded from that category (a slightly vaguer status also cloaked the virtual practical independence of the British colony of Southern Rhodesia). By 1961 (when South Africa became a fully independent republic and left the Commonwealth) twenty-four new African states had come into existence. There are now over fifty.

In 1957 Ghana had been the first ex-colonial new nation to emerge in sub-Saharan Africa. As Africans shook off colonialism, their problems quickly surfaced. Over the next twenty-seven years twelve wars were to be fought in Africa and thirteen heads of state would be assassinated. There were two especially bad outbreaks of strife. In the former Belgian Congo an attempt by the mineral-rich region of Katanga to break away provoked a civil war in which rival Soviet and American influences quickly became entangled, while the United Nations strove to restore peace. Then, at the end of the 1960s, came an even more distressing episode, a civil war in Nigeria, hitherto one of the most stable and promising of the new African states. This, too, drew non-Africans to dabble in the bloodbath (one reason was that Nigeria had joined the ranks of the oil producers). In other countries, there were less bloody, but still fierce, struggles between factions, regions and tribes, which distracted the small westernized élites of politicians and encouraged them to abandon democratic and liberal principles much talked of in the heady days when a colonial system was in retreat.

In many of the new nations, the need, real or imaginary, to prevent disintegration, suppress open dissent and strengthen central authority, had led by the 1970s to one-party, authoritarian government or to the exercise of political authority by soldiers (it was not unlike the history of the new nations of South America after the Wars of Liberation). Often, opposition to the ‘national’ party that had emerged in the run-up to independence in a particular country would be stigmatized as treason once independence was achieved. Nor did the surviving regimes of an older independent Africa escape. Impatience with an

ancien régime

seemingly incapable of providing peaceful political and social change led in 1974 to revolution in Ethiopia. The setting aside of the ‘Lion of Judah’ was almost incidentally the end

of the oldest Christian monarchy in the world (and of a line of kings supposed in one version of the story to run back to the son of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba). A year later, the soldiers who had taken power seemed just as discredited as their predecessors. From similar changes elsewhere in Africa there sometimes emerged tyrant-like political leaders who reminded Europeans of earlier dictators, but this comparison may be misleading. Africanists have gently suggested that many of the ‘strong men’ of the new nations can be seen as the inheritors of the mantle of pre-colonial African kingship, rather than in western terms. Some were simply bandits, however.

Their own troubles did not diminish the frequent irritation with which many Africans reacted to the outside world. Some of the roots of this may not lie very deep. The mythological drama built on the old European slave trade, which Africans were encouraged to see as a supreme example of racial exploitation, had been a European and North American creation. A sense of political inferiority, too, lay near the surface in a continent of relatively powerless states (some with populations of less than a million). In political and military terms, a disunited Africa could not expect to have much weight in international affairs, although attempts were made to overcome the weakness that arose from division. One abortive example was that of 1958 to found a United States of Africa; it opened an era of alliances, partial unions, and essays in federation, which culminated in the emergence in 1963 of the Organization for African Unity (the OAU), largely thanks to the Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie. Politically, though, the OAU has had little success, although in 1975 it concluded a beneficial trade negotiation with Europe in defence of African producers.

The very disappointment of much of the early political history of independent Africa directed thoughtful politicians towards cooperation in economic development, above all in relation to Europe, whose former colonial powers remained Africa’s most important source of capital, skill and counsel. But the economic record of black Africa has been dreadful. In 1960, food production was still roughly keeping pace with population growth, but by 1982 in all but seven of the thirty-nine sub-Saharan countries it was lower per head than it had been in 1970. Corruption, misconceived policies, and preoccupation with showy prestige investment projects squandered economic aid from the developed world. Even in 1965, the GNP of the entire continent had been less than that of Illinois and in more than half of African countries manufacturing output went down in the 1980s. On these feeble economies there had fallen first the blow of the oil crisis of the early 1970s and then the trade recession that followed. The shattering effects for Africa were made even worse soon after by the onset of

repeated drought. In 1960 Africa’s GNP had been growing at the unexciting, but still positive annual rate of about 1.6 per cent; the trend soon turned downward and in the first half of the 1980s was falling at a rate of 1.7 per cent a year. It hardly seems a surprise that in 1983 the UN Economic Commission for Africa already described the picture of the continent’s economy emerging from the historical trends as ‘almost a nightmare’.

Unsurprisingly, political cynicism flourished and many of the leaders of the independence era seemed to lose their way. Too many of them showed an almost complete lack of self-criticism and often a frustration expressed in the encouragement of new resentments (sometimes exacerbated by external attempts to entangle Africans in the Cold War). These could be disappointing, too. Marxist revolution had little success. Paradoxically, it was only in Ethiopia, most feudally backward of independent African states, and the former Portuguese colonies, the least-developed former colonial territories, that formally Marxist regimes took root. Former French and British colonies were hardly affected.