The New Penguin History of the World (207 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Not far into her premiership, she found herself in 1982 presiding unexpectedly over what may well prove to have been Great Britain’s last colonial war. The reconquest of the Falkland Islands after their brief occupation by Argentine forces was in logistic terms alone a great feat of arms as well as a major psychological and diplomatic success. The prime minister’s instincts to fight for the principles of international law and for the islanders’ right to say by whom they should be governed were well-attuned to the popular mood. She also correctly judged the international possibilities. After an uncertain start (unsurprising, given its traditional sensitivity over Latin America), the United States provided important practical and clandestine help. Chile, by no means easy with her restive neighbour, was not disposed to object to British covert operations on the mainland of South America. More important, most of the EC countries supported the isolation of Argentina in the UN, and resolutions that condemned the Argentine action. It was especially notable that the British had from the start the support (not often offered to them so readily) of the French government, which knew a threat to vested rights when it saw one.

It now seems clear that Argentinian action had been encouraged by the misleading impressions of likely British reactions gained from British diplomacy in previous years (for this reason, the British foreign secretary resigned at the outset of the crisis). Happily, one political consequence was the fatal wounding in its prestige and cohesiveness of the military regime that ruled Argentina and its replacement at the end of 1983 by a constitutional and elected government. In the United Kingdom, Mrs Thatcher’s prestige rose with national morale; abroad, too, her standing was enhanced, and this was important. For the rest of the decade it provided the country with an influence with other heads of state (notably the American president) which the raw facts of British strength could scarcely have sustained by themselves. Not everyone agreed that this influence was always advantageously deployed. Like those of General de Gaulle, Mrs Thatcher’s personal convictions, preconceptions and prejudices were always very visible and she, like him, was no European, if that meant allowing emotional or even practical commitment to Europe to blunt personal visions of national interest. At home, meanwhile, she transformed the terms of British politics, and perhaps of cultural and social debate, dissolving a long-established

bien-pensant

consensus about national goals. This, together with the undoubted radicalism of many of her specific policies, awoke both enthusiasm and an unusual animosity. Yet she failed to achieve some of her most important aims. Ten years after she took up office, government was playing a greater, not a smaller, role in many areas of society, and the public money spent on health and social security had gone up a third in real terms since 1979 (without satisfying greatly increased demand).

Although Mrs Thatcher had led the Conservatives to three general election victories in a row (a unique achievement in British politics up to then), many in her party came to believe she would be a vote-loser in the next contest, which could not be far away. Faced with the erosion of loyalty and support, she resigned in 1990, leaving to her successor rising unemployment and a bad financial situation. But it seemed likely that British policy might now become less obstructive in its approach to the Community and its affairs and less rhetorical about it.

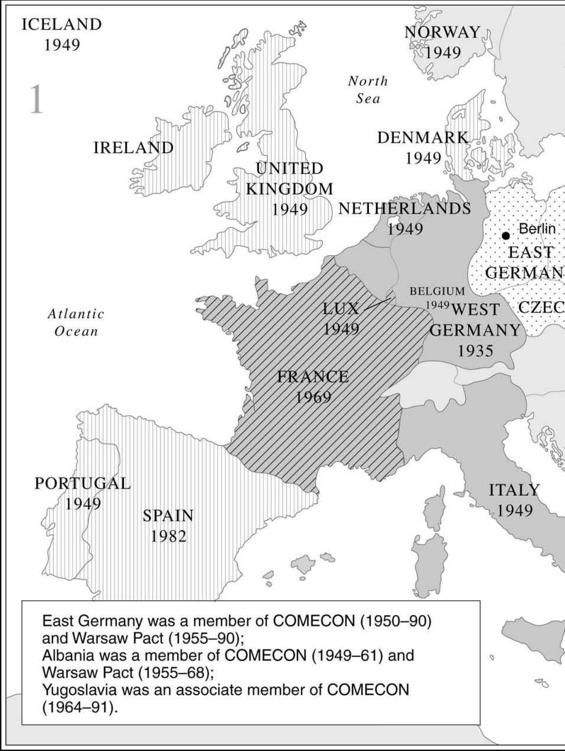

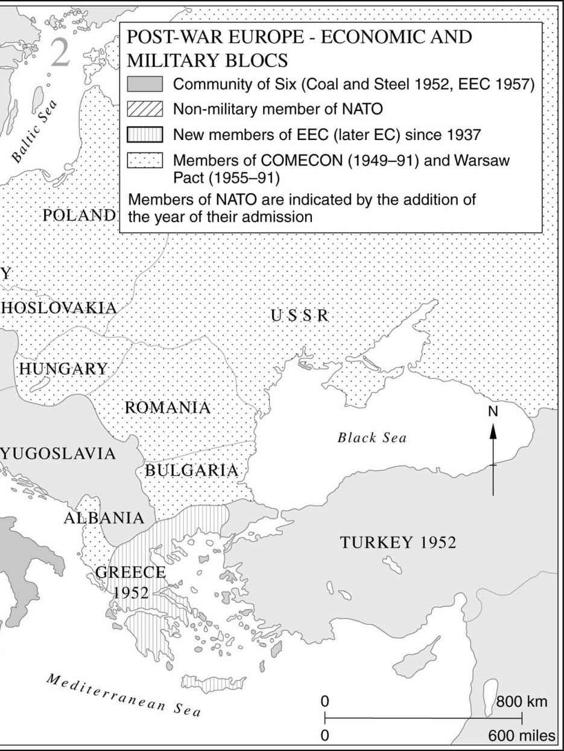

The 1970s had been difficult years for all the members of the EEC. Growth fell away and individual economies reeled under the impact of the oil crisis. This contributed to institutional bickering and squabbling (particularly on economic and financial matters), which had reminded Europeans of the limits to what was so far achieved. It continued in the 1980s and, coupled with uneasiness about the success of the Far Eastern economic sphere, dominated by Japan, and a growing realization that other

nations would wish to join the ten, led to further crystallization of ideas about the Community’s future. Many Europeans saw more clearly that greater unity, a habit of cooperation and an increasing prosperity were prerequisites of Europe’s political independence, but some also felt an emerging sense that such independence would always remain hollow unless Europe, too, could turn herself into a superpower.

Comfort could be drawn by enthusiasts from further progress in integration. In 1979 the first direct elections to the European parliament were already being held. Greece in 1981, Spain and Portugal in 1986, were soon to join the Community. In 1987 the foundations of a common European currency and monetary system were drawn up (although the United Kingdom did not agree) and it was settled that 1992 should be the year which would see the inauguration of a genuine single market, across whose national borders goods, people, capital and services were to move freely. Members even endorsed in principle the idea of European political union, although the British and French had notable misgivings. This by no means made at once for greater psychological cohesion and comfort as the implications emerged, but it was an indisputable sign of development of some sort.

In the years since the Treaty of Rome, western Europe had come a very long way, further, perhaps, than was always grasped by men and women born and grown to maturity under it. Underlying the institutional changes, too, were slowly growing similarities – in politics, social structure, consumption habits and beliefs about values and goals. Even the old disparities of economic structure had greatly diminished, as the decline in numbers and increase in prosperity of French and German farmers showed. On the other hand, new problems had presented themselves as poorer and perhaps politically less stable countries had joined the EC. That there had been huge convergences could not be contested. What was still unclear was what this might imply for the future.

NEW CHALLENGES TO THE COLD WAR WORLD ORDER

In December 1975 Gerald Ford became the second American president to visit China. The adjustment of his country’s deep-seated distrust and hostility towards the People’s Republic had begun with the slow recognition of the lessons of Vietnam. On the Chinese side, change was a part of an even greater development: China’s resumption of an international and regional role appropriate to her historic stature and potential. This could only come

to fruition after 1949 and by the mid-1970s it was complete. An approach towards establishing normal relations with the United States was now possible. Formal recognition of what had already been achieved came in 1978. In a Sino-American agreement the United States made the crucial concession that its forces should be withdrawn from Taiwan and that official diplomatic relations with the island’s KMT government should be ended.

Mao had died in September 1976. The threat of the ascendancy of a ‘gang of four’ of his coadjutors (one was his widow), who had promoted the policies of the Cultural Revolution, was quickly averted by their arrest (and, eventually, trial and condemnation in 1981). Under new leadership dominated by party veterans, it soon became clear that the excesses of the Cultural Revolution were to be corrected. In 1977 there rejoined the government as a vice-premier the twice-previously disgraced Deng Xiaoping, firmly associated with the contrary trend (his son had been crippled by beatings from the Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution). The most important change, though, was that China’s long-awaited economic recovery was at last attainable. Scope was now to be given to individual enterprise and profit motive, and economic links with non-communist countries were to be encouraged. The aim was to resume the process of technological and industrial modernization.

The major definition of the new course was undertaken in 1981 at the plenary session of the central committee of the party that met that year. It undertook, too, the delicate task of distinguishing the positive achievements of Mao, a ‘great proletarian revolutionary’, from what it now identified as his ‘gross mistakes’ and his responsibility for the setbacks of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. For all the comings and goings in CCP leadership and the mysterious debates and sloganizing which continued to obscure political realities, and although Deng Xiaoping and his associates had to work through a collective leadership that included conservatives, the 1980s were to be shaped by a new current. Modernization had at last been given precedence over Marxist socialism, even if that could hardly be said aloud (when the secretary-general of the party pronounced in 1986 the incautious and amazing judgement that ‘Marx and Lenin cannot solve our problems’, he was soon dismissed). Marxist language still pervaded the rhetoric of government. Some said China was resuming the ‘capitalist road’. This, too, was obscuring, though natural. There persisted in the party and government a clear grasp of the need for positive planning of the economy; but there was a new recognition of practical limits and a willingness to try to discriminate more carefully between what was and was not within the scope of effective regulation in

the pursuit of the major goals of economic and national strength, the improvement of living standards, and a broad egalitarianism.

One remarkable change was that agriculture was virtually privatized in the next few years in the sense that, although they were not given the freeholds of their land, peasants were encouraged to sell produce freely in the markets. New slogans – ‘to get rich is glorious’ – were coined to encourage the development of village industrial and commercial enterprise, and a pragmatic road to development was signposted with ‘four modernizations’. Special economic areas, enclaves for free trade with the capitalist world, were set up; the first at Canton, the historic centre of Chinese trade with the West. It was not a policy without costs – grain production fell at first, inflation began to show itself in the early 1980s and foreign debt rose. Some blamed the growing visibility of crime and corruption on the new line.

Yet of its economic success there can be no doubt. Mainland China began in the 1980s to show that perhaps an economic ‘miracle’ like that of Taiwan was within her grasp. By 1986 she was the second largest producer of coal in the world, and the fourth largest of steel. GDP rose at more than 10 per cent a year between 1978 and 1986, while industrial output had doubled in value in that time. Per capita peasant income nearly tripled and by 1988 the average peasant family was estimated to have about six months’ income in the savings bank. Taking a longer perspective, the contrasts are even more striking, for all the damage done by the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. The value of foreign trade multiplied roughly twenty-five times in per capita terms between 1950 and the middle of the 1980s. The social benefits that have accompanied such changes are also clear: increased food consumption and life expectancy, a virtual end to many of the fatal and crippling diseases of the old regime, and a huge inroad into mass illiteracy. China’s continuing population growth was alarming and prompted vigorous measures of intervention, but it had not, as had India’s, devoured the fruits of economic development.

The new line specifically linked modernization to strength. Thus it reflected the aspirations of China’s reformers ever since the May 4th Movement and of some even earlier. China’s international weight had already been apparent in the 1950s; it now began to show itself in different ways. In 1984 came agreement with the British over terms for the reincorporation of Hong Kong in 1997 on the expiration of the lease covering some of its territories. A later agreement with the Portuguese provided for the resumption of Macao, too. It was a blemish on the general recognition of China’s due standing that among its neighbours Vietnam (with which China’s relations at one time degenerated into open warfare, when the two countries

were rivals for the control of Cambodia) remained hostile; but the Taiwanese were somewhat reassured by Chinese promises that the reincorporation of the island into the territory of the republic in due course would not endanger its economic system. Similar assurances were given over Hong Kong. Like the establishment of special trading enclaves on the mainland where external commerce could flourish, such statements underlined the importance China’s new rulers attached to commerce as a channel of modernization. China’s sheer size gave such a policy direction importance over a wide area. By 1985 the whole of East and South-East Asia constituted a trading zone of unprecedented potential.