The New Penguin History of the World (59 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

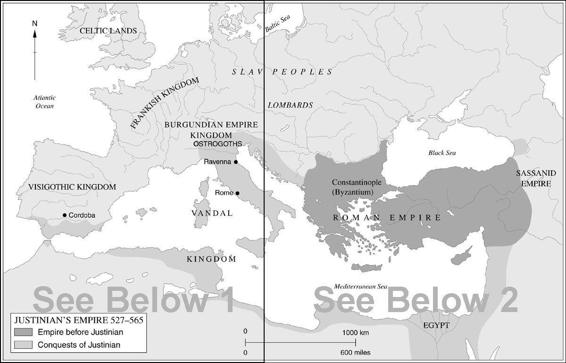

The eastern emperors had not seen these changes with indifference. But troubles in their own domains hamstrung them and in the fifth century their barbarian generals dominated them too. They watched with apprehension the last years of the puppet emperors of Ravenna but recognized Odoacer, the deposer of the last of them. They maintained a formal claim to rule over a single empire, east and west, without actually questioning Odoacer’s independence in Italy until an effective replacement was available in Theodoric, to whom the title of patrician was given. Meanwhile, Persian wars and the new pressure of Slavs in the Balkans were more than enough to deal with. It was not until the accession of the Emperor Justinian in 527 that reality seemed likely to be restored to imperial government.

In retrospect Justinian seems something of a failure. Yet he behaved as people thought an emperor should; he did what most people still expected that a strong emperor would one day do. He boasted that Latin was his native tongue; for all the wide sweep of the empire’s foreign relations, he could still think plausibly of reuniting and restoring the old empire, centred on Constantinople though it now had to be. We labour under the handicap of knowing what happened, but he reigned a long time and his contemporaries were more struck by his temporary successes. They expected them to herald a real restoration. After all, no one could really conceive a world without the empire. The barbarian kings of the West gladly deferred to Constantinople and accepted titles from it; they did not grasp at the purple themselves. Justinian sought autocratic power, and his contemporaries found the goal both comprehensible and realistic. There is a certain grandeur about his conception of his role; it is a pity that he should have been so unattractive a man.

Justinian was almost always at war. Often he was victorious. Even the costly Persian campaigns (and payments to the Persian king) were successful in the limited sense that they did not lose the empire much ground. Yet they were a grave strategic handicap; the liberation of his resources for a policy of recovery in the West, which had been Justinian’s aim in his first peace with the Persians, always eluded him. Nevertheless, his greatest general, Belisarius, destroyed Vandal Africa and recovered that country

for the empire (though it took ten years to reduce it to order). He went on to invade Italy and begin the struggle which ended in 554 with the final eviction of the Ostrogoths from Rome and the unification once more of all Italy under imperial rule, albeit an Italy devastated by the imperial armies as it had never been by the barbarians. These were great achievements, though badly followed up. More were to follow in southern Spain, where the imperial armies exploited rivalry between Visigoths and again set up imperial government in Córdoba. Throughout the western Mediterranean, too, the imperial fleets were supreme; for a century after Justinian’s death, Byzantine ships moved about unmolested.

It did not last. By the end of the century most of Italy was gone again, this time to the Lombards, another Germanic people and the final extinguishers of imperial power in the peninsula. In eastern Europe, too, in spite of a vigorous diplomacy of bribery and missionary ideology, Justinian had never been successful in dealing with the barbarians. Perhaps enduring success there was impossible. The pressure from behind on these migrant peoples was too great and, besides, they could see great prizes ahead; ‘the barbarians,’ wrote one historian of the reign, ‘having once tasted Roman wealth, never forgot the road that led to it’. By Justinian’s death, in spite of his expensive fortress-building, the ancestors of the later Bulgars were settled in Thrace and a wedge of barbarian peoples separated west and east Rome.

Justinian’s conquests, great as they were, could not be maintained by his successors in the face of the continuing threat from Persia, the rise of Slav pressure in the Balkans and, in the seventh century, of a new rival, Islam. A terrible time lay ahead. Yet even then Justinian’s legacy would be operative through the diplomatic tradition he founded, the building of a network of influences among the barbarian peoples beyond the frontier, playing off one against another, bribing one prince with tribute or a title, standing godparent to the baptized children of another. If it had not been for the client princedoms of the Caucasus who were converted to Christianity in Justinian’s day, or his alliance with the Crimean Goths (which was to last seven centuries), the survival of the eastern empire would have been almost impossible. In this sense, too, the reign sets out the ground-plan of a future Byzantine sphere.

Within the empire, Justinian left an indelible imprint. At his accession the monarchy was handicapped by the persistence of party rivalries which could draw upon popular support, but in 532 this led to a great insurrection which made it possible to strike at the factions and, though much of the city was burned, this was the end of domestic threats to Justinian’s autocracy. It showed itself henceforth more and more consistently and nakedly.

Its material monuments were lavish; the greatest is the basilica of

St Sophia itself (532–7), but all over the empire public buildings, churches, baths and new towns mark the reign and speak for the inherent wealth of the eastern empire. The richest and most civilized provinces were in Asia and Egypt; Alexandria, Antioch and Beirut were their great cities. A non-material, institutional, monument of the reign was Justinian’s codification of Roman law. In four collections a thousand years of Roman jurisprudence was put together in a form which gave it deep influence across the centuries and helped to shape the modern idea of the state. Justinian’s efforts to win administrative and organizational reform were far less successful. It was not difficult to diagnose ills known to be dangerous as long before as the third century. But given the expense and responsibilities of Empire, permanent remedies were hard to find. The sale of offices, for example, was known to be an evil and Justinian abolished it, but then had to tolerate it when it crept back.

The main institutional response to the empire’s problem was a progressive regimentation of its citizens. In part, this was in the tradition of regulating the economy which he had inherited. Just as peasants were tied to the soil, craftsmen were now attached to their hereditary corporations and guilds; even the bureaucracy tended to become hereditary. The resulting rigidity was unlikely to make imperial problems easier to solve.

It was unfortunate, too, that a quite exceptionally disastrous series of natural calamities fell on the east at the beginning of the sixth century: they go far to explain why it was hard for Justinian to leave the empire in better fettle than he found it. Earthquake, famine, plague devastated the cities and even the capital itself, where men saw phantoms in the streets. The ancient world was a credulous place, but tales of the emperor’s capacity to take off his head and then put it on again, or to disappear from sight at will, suggest that under these strains the mental world of the eastern empire was already slipping its moorings in classical civilization. Justinian was to make the separation easier by his religious outlook and policies, another paradoxical outcome, for it was far from what he intended. After it had survived for eight hundred years, he abolished the academy of Athens; he wanted to be a Christian emperor, not a ruler of unbelievers, and decreed the destruction of all pagan statues in the capital. Worse still, he accelerated the demotion of the Jews in civic status and the reduction of their freedom to exercise their religion. Things had already gone a long way by then. Pogroms had long been connived at and synagogues destroyed; now Justinian went on to alter the Jewish calendar and interfere with the Jewish order of worship. He even encouraged barbarian rulers to persecute Jews. Long before the cities of western Europe, Constantinople had a ghetto.

Justinian was all the more confident of the rightness of asserting imperial authority in ecclesiastical affairs because (like the later James I of England) he had a real taste for theological disputation. Sometimes the consequences were unfortunate; such an attitude did nothing to renew the loyalty to the empire of the Nestorians and Monophysites, heretics who had refused to accept the definitions of the precise relationship of God the Father to God the Son laid down in 451 at a council at Chalcedon. The theology of such deviants mattered less than the fact that their symbolic tenets were increasingly identified with important linguistic and cultural groups. The empire began to create its Ulsters. Harrying heretics intensified separatist feeling in parts of Egypt and Syria. In the former, the Coptic Church went its own way in opposition to Orthodoxy in the later fifth century and the Syrian Monophysites followed, setting up a ‘Jacobite’ church. Both were encouraged and sustained by the numerous and enthusiastic monks of those countries. Some of these sects and communities, too, had important connections outside the empire, so that foreign policy was involved. The Nestorians found refuge in Persia and, though not heretics, the Jews were especially influential beyond the frontiers; Jews in Iraq supported Persian attacks on the empire and Jewish Arab states in the Red Sea interfered with the trade routes to India when hostile measures were taken against Jews in the empire.

Justinian’s hopes of reuniting the western and eastern Churches were to be thwarted in spite of his zeal. A potential division between them had always existed because of the different cultural matrices in which each had been formed. The western Church had never accepted the union of religious and secular authority which was the heart of the political theory of the eastern empire; the empire would pass away as others had done (and the Bible told) and it would be the Church which would prevail against the gates of hell. Now such doctrinal divergences became more important, and separation had been made more likely by the breakdown in the West. A Roman pope visited Justinian and the emperor spoke of Rome as the ‘source of priesthood’, but in the end two Christian communions were first to go their own ways and then violently to quarrel. Justinian’s own view, that the emperor was supreme, even on matters of doctrine, fell victim to clerical intransigence on both sides.

This seems to imply (as do so many others of his acts) that Justinian’s real achievement was not that which he sought and temporarily achieved, the re-establishment of the imperial unity, but a quite different one, the easing of the path towards the development of a new, Byzantine civilization. After him, it was a reality, even if not yet recognized. Byzantium was evolving away from the classical world towards a style clearly related to it, but independent of it. This was made easier by contemporary developments in both eastern and western culture, by now overwhelmingly a matter of new tendencies in the Church.

As often in later history, the Church and its leaders had not at first recognized or welcomed an opportunity in disaster. They identified themselves with what was collapsing and understandably so. The collapse of Empire was for them the collapse of civilization; the Church in the West was, except for municipal authority in the impoverished towns, often the sole institutional survivor of

romanitas

. Its bishops were men with experience of administration, at least as likely as other local notables to be intellectually equipped to grapple with new problems. A semi-pagan population looked to them with superstitious awe and attributed to them near-magical power. In many places they were the last embodiment of authority left when imperial armies went away and imperial administration crumbled, and they were lettered men among a new unlettered ruling class which craved the assurance of sharing the classical heritage. Socially, they were often drawn from the leading provincial families; that meant that they were sometimes great aristocrats and proprietors with material resources to support their spiritual role. Naturally, new tasks were thrust upon them.