The New Penguin History of the World (74 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The Ottomans, as they became known in Europe, were Osmanlis, one of the Turkish peoples who had emerged from the collapse of the sultanate of Rum. When the Seljuks arrived there they found on the borderlands between the dissolved Abbasid caliphate and the Byzantine empire a number of Muslim marcher lords, petty princes called

ghazis

, sometimes Turkish by race, lawless, independent and the inevitable beneficiaries of

the ebbing of paramount power. Their existence was precarious, and the Byzantine empire had absorbed some of them in its tenth-century recovery, but they were hard to control. Many survived the Seljuk era and benefited from the Mongol destruction of the Seljuks at a time when Constantinople was in the hands of the Latins. One of these

ghazis

was Osman, a Turk who may have been an Oghuz. He showed leadership and enterprise, and men gathered to him. His quality is shown by the transformation of the word

ghazi

: it came to mean ‘warrior of the faith’. Fanatical frontiersmen, his followers seem to have been distinguished by a certain spiritual

élan

. Some of them were influenced by a particular mystical tradition within Islam. They also developed highly characteristic institutions of their own. They had a military organization somewhat like that of merchant guilds or religious orders in medieval Europe and it has been suggested that the West learnt in these matters from the Ottomans. Their situation on a curious borderland of cultures, half-Christian, half-Islamic, must also have been provoking. Whatever its ultimate source, their staggering record of conquest rivals that of Arab and Mongol. They were in the end to reassemble under one ruler the territory of the old eastern Roman empire and more.

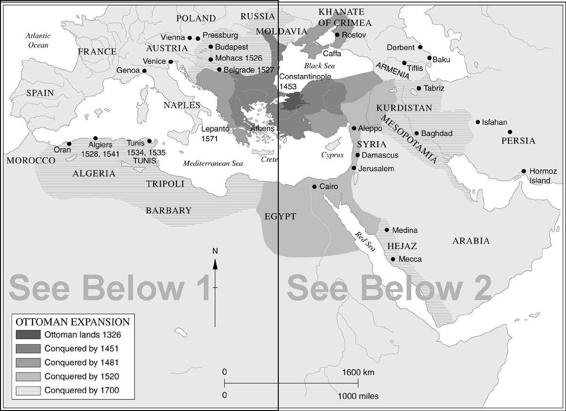

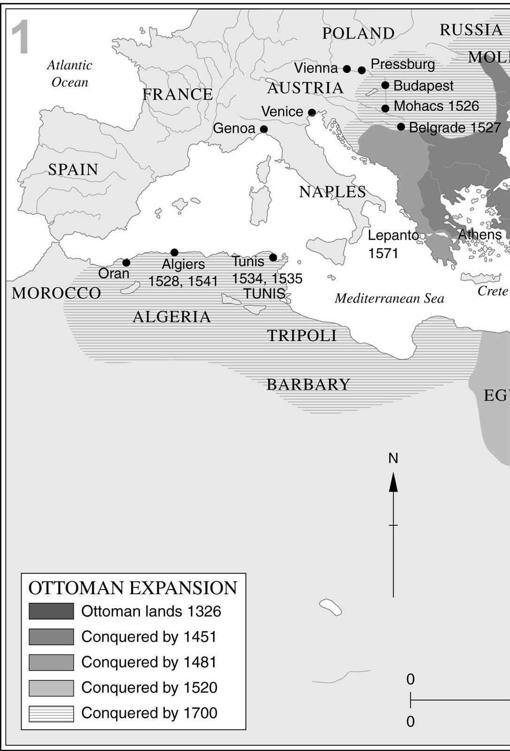

The first Ottoman to take the title of Sultan did so in the early fourteenth century. This was Orkhan, Osman’s son. Under him began the settlement of conquered lands which was eventually to be the basis of Ottoman military power. Like his foundation of the ‘Janissaries’, the new infantry corps which he needed to fight in Europe, the change marked an important stage in the evolution of Ottoman empire away from the institutions of a nomadic people of natural cavalrymen. Another sign that things were settling down was Orkhan’s issue of the first Ottoman coinage. At his death he ruled the strongest of the post-Seljuk states of Asia Minor as well as some European lands. Orkhan was important enough to be three times called upon by the Byzantine emperor for help and he married one of the emperor’s daughters.

His two successors steadily ate up the Balkans, conquering Serbia and Bulgaria. They defeated another ‘crusade’ against them in 1396 and went on to take Greece. In 1391 they began their first siege of Constantinople, which they maintained successfully for six years. Meanwhile, Anatolia was absorbed by war and diplomacy. There was only one bad setback, the defeat by Timur which brought on a succession crisis and almost dissolved the Ottoman empire. The advance was then resumed and the Venetian empire now began to suffer, too. But for Byzantine and Turk alike, the struggle was essentially a religious one and its heart was the possession of the thousand-year-old Christian capital, Constantinople.

It was under Mehmet II, named the Conqueror, that in 1453 Constantinople fell to the Turks and the western world shuddered. It was a great victory, depleted though the resources of Byzantium were, and Mehmet’s personal achievement, for he had persisted against all obstacles. The age of gunpowder was now well under way and he had a Hungarian engineer build him a gigantic cannon, whose operation was so cumbersome that it could only be moved by a hundred oxen and fired only seven times a day (the Hungarian’s assistance had been turned down by the Christians though the fee he asked was a quarter of what Mehmet gave him). It was a failure. Mehmet did better with orthodox methods, driving his soldiers forward ruthlessly, cutting them down if they flinched from the assault. Finally, he carried seventy ships overland to get them behind the imperial squadron guarding the Horn.

The last attack began early in April 1453. After nearly two months, on the evening of 28 May, Roman Catholics and Orthodox alike gathered in St Sophia and the fiction of the religious reunion was given its last parade. The Emperor Constantine XI, eightieth in succession since his namesake, the great first Constantine, took communion and then went out to die worthily, fighting. Soon afterwards, it was all over. Mehmet entered the city, went straight to St Sophia and there set up a triumphant throne. The church which had been the heart of Orthodoxy was made a mosque.

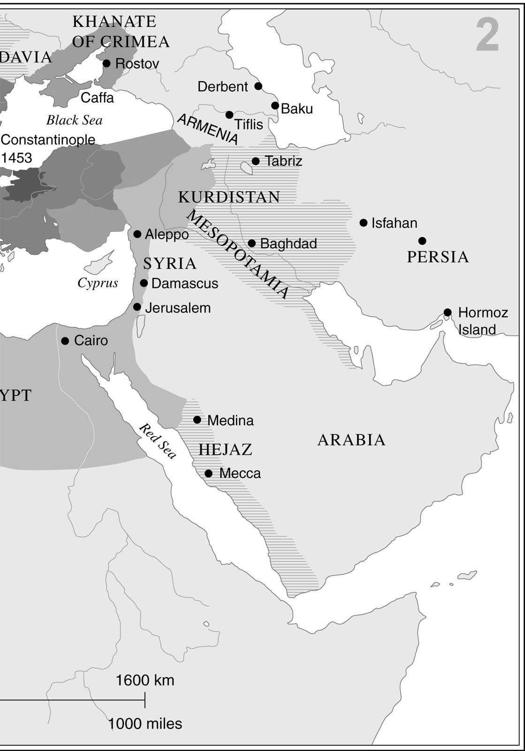

This was only a step, great as it was; the banner of Ottoman success was to be raised yet higher. The invasion of Serbia in 1459 was almost at once followed by the conquest of Trebizond. Unpleasant though this may have been for the inhabitants, it would merit only a footnote to the roll of Turkish conquest were it not also the end of Hellenism. At this remote spot on the south-eastern coast of the Black Sea in 1461 the world of Greek cities made possible by the conquest of Alexander the Great gave its last gasp. It marked an epoch as decisively as the fall of Constantinople, which a humanist pope bewailed as ‘the second death of Homer and Plato’ (following words with action, he then took command of a crusading army, but died before it could leave its base at Ancoma). From Trebizond, Turkish conquest rolled on. In the same year the Turks occupied the Peloponnese. Two years later they took Bosnia and Herzegovina. Albania and the Ionian islands followed in the next twenty years. In 1480 they captured the Italian port of Otranto and held it for nearly a year. In 1517 Syria and Egypt were conquered. They took longer to pick up the remainder of the Venetian empire, but at the beginning of the sixteenth century Turkish cavalry were near Vicenza. Belgrade fell to them in 1521, and a year later Rhodes was seized. In 1526 at Mohacs the Turks wiped out the army of the Hungarian king in a defeat which is remembered still as the black day of Hungarian history. Three years later they besieged Vienna for the first time. In 1571 Cyprus fell to them and nearly a century later Crete. By this time they were deep into Europe. They again besieged Vienna in the seventeenth century; their second failure to take it was the high-water mark of Turkish conquest. But they were still conquering new territory in the Mediterranean as late as 1715. Meanwhile, they had taken Kurdistan from Persia, with whom they had hardly ceased to quarrel since the appearance of a new dynasty there in 1501, and had sent an army as far south as Aden.

The Ottoman empire was to be of unique importance to Europe. It is one of the big differences marking off the history of its eastern from that of its western half. It was crucial that the Church survived and was tolerated in the Ottoman empire. That preserved the heritage of Byzantium for its Slav subjects (and, indeed, ended any threat to the supremacy of the patriarch at Constantinople either from the Catholics or from ethnic Orthodox churches in the Balkans). Outside the former empire, only one important focus of Orthodoxy remained; it was crucial that the Orthodox Church was now the heritage of Russia. The establishment of the Ottoman empire for a time sealed off Europe from the Near East and the Black Sea and, therefore, in large measure from the land-routes to Asia. The Europeans had really only themselves to blame; they had never been (and were never to be) able to unite effectively against the Turks. Byzantium had been left to her fate. ‘Who will make the English love the French? Who will unite

Genoese and Aragonese?’ asked one Pope despairingly; not long after, one of his successors was sounding out the possibilities of Turkish help against France. Yet the challenge had awoken another sort of response, for even before the fall of Constantinople Portuguese ships were picking their way southwards down the African coast to look for a new route to the spices of the East and, possibly, an African ally to take the Turk in the flank from the south. People had mused over finding a way around the Islamic barrier since the thirteenth century, but the means had long been inadequate. By one of history’s ironies they were just about to become available as Ottoman power reached its menacing peak.

Behind the Ottoman frontiers a new multi-racial empire was organized. Mehmet was a man of wide, if volatile, sympathies and later Turks found it hard to understand his forbearance to the infidel. He was a man who could slaughter a boy, the godson of the emperor, because his sexual advances were refused, but he allowed a band of Cretans who would not surrender to sail away after the fall of Constantinople because he admired their courage. He seems to have wanted a multi-religious society. He brought back Greeks to Constantinople from Trebizond and appointed a new patriarch under whom the Greeks were eventually given a kind of self-government. The Turkish record towards Jew and Christian was better than that of Spanish Christians towards Jew and Muslim. Constantinople remained a great cosmopolitan city (and with a population of 700,000 in 1600, one far larger than any other in geographical Europe).

Thus the Ottomans reconstructed a great power in the eastern Mediterranean and the sixteenth century was a great one for Islamic empire. But this was not only true in Europe and Africa, while the Ottomans rebuilt something like the Byzantime empire, another power was emerging in Persia which was also reminiscent of the past. Between 1501 and 1736 the Safavid dynasty ruled Persia, uniting all the Persian lands for the first time since the Arab invasions had shattered the Sassanids. Like their predecessors, the Safavids were not themselves Persian. Since the days of the Sassanids, conquerors had come and gone. The continuities of Persian history were meanwhile provided by culture and religion. Persia was defined by geography, by its language and by Islam, not by the maintenance of national dynasties. The Safavids were originally Turk,

ghazis

like the Osmanlis, and succeeded, like them, in distancing possible rivals. The first ruler they gave to Persia was Ismail, a descendant of the fourteenth-century tribal ruler who had given his name to the line.

At first, Ismail was only the most successful leader of a group of warring Turkish tribes, rather like those further west, exploiting similar opportunities. The Timurid inheritance had been in dissolution since the middle of

the fifteenth century. In 1501 Ismail defeated the people known as the White Sheep Turks, entered Tabriz and proclaimed himself shah. Within twenty years he had carved out an enduring state and had also embarked upon a long rivalry with the Ottoman, even seeking support against them from the Holy Roman Empire. This had a religious dimension, for the Safavids were Shi’ites and made Persia Shi’ite, too. When in the early sixteenth century the caliphate passed to the Ottomans they became the leaders of Sunnite Muslims who saw the caliphs as the proper interpreters and governors of the faith. The Shi’ites were therefore automatically anti-Ottoman. Ismail’s establishment of the sect in Persia thus gave a new distinctiveness to Persia’s civilization which was to prove of great importance in preserving it.

His immediate successors had to fight off the Turks several times before a peace was made in 1555, which left Persia intact and opened Mecca and Medina to Persian pilgrims. There were domestic troubles too, and fighting for the throne, but in 1587 there came to it one of the most able of Persian rulers, Shah Abbas the Great. Under his rule the Safavid dynasty was at its zenith. Politically and militarily he was very successful, defeating the Uzbeks and the Turks and taming the old tribal loyalties which had weakened his predecessors. He had important advantages: the Ottomans were distracted in the West, the potential of Russia was sterilized by internal troubles and Moghul India was past its peak. He was clever enough to see that Europe could be enrolled against the Turk. Yet a favourable conjuncture of international forces did not lead to schemes of world conquest. The Safavids did not follow the Sassanid example. They never took the offensive against Turkey except to recover earlier loss and they did not push north through the Caucasus to Russia, or beyond Transoxiana.