The New Penguin History of the World (73 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

In its relations with the rest of the world, the Mongol empire came to show the influence of China in its fundamental presuppositions. The khans were the representatives on earth of the one sky god, Tengri; his supremacy

had to be acknowledged, though this did not mean that the practice of other religions would not be tolerated. But it did mean that diplomacy in the western sense was inconceivable. Like the Chinese emperors whom they were to replace, the khans saw themselves as the upholders of a universal monarchy; those who came to it had to come as suppliants. Ambassadors were the bearers of tribute, not the representatives of powers of equal standing. When in 1246 emissaries from Rome conveyed papal protests against the Mongol treatment of Christian Europe and a recommendation that he should be baptized, the new Great Khan’s reply was blunt: ‘If you do not observe God’s command, and if you ignore my command, I shall know you as my enemy. Likewise I shall make you understand.’ As for baptism, the pope was told to come in person to serve the khan. It was not an isolated message, for another pope had the same reply from the Mongol governor of Persia a year later: ‘If you wish to keep your land, you must come to us in person and thence go on to him who is master of the earth. If you do not, we know not what will happen: only God knows.’

The cultural influences playing upon the Mongol rulers and their circle were not only Chinese. There is much evidence of the importance of Nestorian Christianity at the Mongol court and it encouraged European hopes of a

rapprochement

with the khans. One of the most remarkable western visitors to the khan, the Franciscan William of Roebruck, was told just after New Year 1254, by an Armenian monk, that the Great Khan would be baptized a few days later, but nothing came of it. William went on, however, to win a debate before him, defending the Christian faith against Muslim and Buddhist representatives and coming off best. This was, in fact, just the moment at which Mongol strength was being gathered for the double assault on world power, against Sung China and the Muslims, which was finally checked in Syria by the Mamelukes in 1260.

Not that this was the end of attempts by Mongols to conquer the Levant. None was successful, though; the Mongols’ quarrels among themselves had given the Mamelukes a clear field for too long. Logically, Christians regretted the death of Hulugu, the last khan to pose a real threat to the Near East for decades. After him a succession of Il-khans, or subordinate khans, ruled in Persia, preoccupied with their quarrels with the Golden and White Hordes. Gradually Persia recovered under them from the invasions it had suffered earlier in the century. As in the East, the Mongols ruled through locally recruited administrators and were tolerant of Christians and Buddhists, though not, at first, of Muslims. There was a clear sign of a change in the relative position of Mongol and European when the II-khans began to suggest to the pope that they should join in an alliance against the Mamelukes.

When Kubilai Khan died in China in 1294 one of the few remaining links that held together the Mongol empire had gone. In the following year an Il-khan called Ghazan made a momentous break with the Mongol tradition; he became a Muslim. Since then the rulers of Persia have always been Muslim. But this did not do all that might have been hoped and the Il-khan died young, with many problems unsolved. To embrace Islam had been a bold stroke, but it was not enough. It had offended many Mongols and in the last resort the khans depended upon their captains. Nevertheless, the contest with the Mamelukes was not yet abandoned. Though in the end unsuccessful, Ghazan’s armies took Aleppo in 1299; he was prayed for in the Ummayad mosque at Damascus the next year. He was the last khan to attempt to realize the plan of Mongol conquest of the Near East set out a half-century before, but was frustrated in the end when the Mamelukes defeated the last Mongol invasion of Syria in 1303. The Il-khan died the following year.

As in China, it soon appeared in Persia that Mongol rule had enjoyed only a brief Indian summer of consolidation before it began to crumble. Ghazan was the last Il-khan of stature. Outside their own lands, his successors could exercise little influence; the Mamelukes terrorized the old allies of the Mongols, the Christian Armenians, and Anatolia was disputed between different Turkish princes. There was little to hope for from Europe, where the illusion of the crusading dream had been dissipated.

Though Mongol power ebbed away, there came one last flash of the old terror in the West as a conqueror appeared who rivalled even Chinghis. In 1369 Timur Lang, or Timur the lame, became ruler of Samarkand. For thirty years the history of the Il-khans had been one of civil strife and succession disputes; Persia was conquered by Timur in 1379. Timur (who has passed into English literature thanks to Marlowe, as Tamberlane) aspired to rival Chinghis. In the extent of his conquests and the ferocity of his behaviour he did; he may even have been as great a leader of men. None the less, he lacked the statesmanship of his predecessors. Of creative art he was barren. Though he ravaged India and sacked Delhi (he was as hard on his fellow Muslims as on Christians), thrashed the khans of the Golden Horde, defeated Mameluke and Turk alike and incorporated Mesopotamia as well as Persia in his own domains, he left little behind. His historic role was, except in two respects, almost insignificant. One negative achievement was the almost complete extinction of Asiatic Christianity in its Nestorian and Jacobite form. This was hardly in the Mongol tradition, but Timur was as much a Turk by blood as a Mongol and knew nothing of the nomadic life of central Asia from which Chinghis came, with its willingness to indulge Christian clergy. His sole positive achievement was

unintentional and temporary: briefly, he prolonged the life of Byzantium. By a great defeat of an Anatolian Turkish people, the Ottomans, in 1402, he prevented them for a while from going in to the kill against the eastern empire.

This was the direction in which Near Eastern history had been moving ever since the Mongols had been unable to keep their grip on Seljuk Anatolia. The spectacular stretch of Mongol campaigning – from Albania to Java – makes it hard to sense this until Timur’s death, but then it was obvious. Before that, the Mongols had already been overthrown in China. Timur’s own legacy crumbled, Mesopotamia eventually becoming the emirate of the attractively named Black Sheep Turks, while his successors for a while still hung on to Persia and Transoxiana. By the middle of the fifteenth century, the Golden Horde was well advanced in its break-up. Though it could still terrorize Russia, the Mongol threat to Europe was long over.

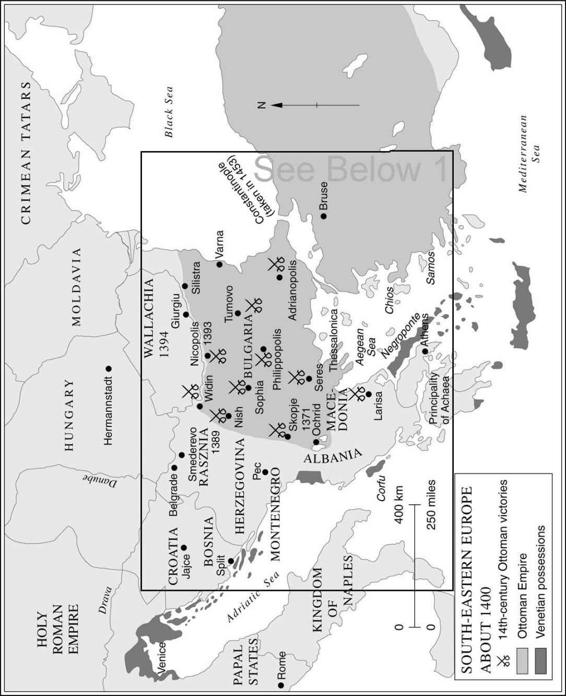

By then, Byzantium was at its last gasp. For more than two centuries it had fought a losing battle for survival, and not merely with powerful Islamic neighbours. It was the West which had first reduced Byzantium to a tiny patch of territory and had sacked its capital. After the mortal wound of 1204 it became merely a small Balkan state. A Bulgarian king had seized the opportunity of that year to assure his country’s independence as one of several ephemeral successor states which made their appearance. Furthermore, on the ruins of Byzantine rule there was established the new western European maritime empire of Venice, the cuckoo in the nest which had been in the first place bribed to enter it. This former client had by the middle of the fourteenth century taken from the Byzantine heritage the whole Aegean complex of islands, with Rhodes, Crete, Corfu and Chios. During that time, too, Venice had kept up a bitter commercial and political struggle with her rival, Genoa, which had herself by 1400 acquired control of the southern coast of the Crimea and its rich trade with the hinterland of Russia.

In 1261 the Byzantines had won back their own capital from the Franks. They did so with the help of a Turkish power in Anatolia, the Osmanlis. Two factors might still benefit the empire; the crucial phase of Mongol aggression was past (though this could hardly have been known and Mongol attacks continued to fall on peoples who cushioned her from them), and in Russia there existed a great Orthodox power which was a source of help and money. But there were also new threats and these outweighed the positive factors. Byzantine recovery in Europe in the later thirteenth century was soon challenged by a Serbian prince with aspirations to empire. He died before he could take Constantinople, but he left the empire with little but the hinterland of the capital and a fragment of

Thrace. Against the Serbs, the empire once more called on Osmanli help. Already firmly established on the Asian shores of the Bosphorus, the Turks took a toehold in Europe at Gallipoli in 1333.

The best that the last eleven emperors, the Palaeologi, could manage in these circumstances was a rearguard action. They lost what was left of Asia Minor to the Osmanlis in 1326 and it was there that the fatal danger lay. In the eastern Black Sea they had an ally in the Greek empire of Trebizond, a great trading state which was just to outlive Byzantium itself, but in Europe they could hope for little. The ambitions of the Venetians and Genoese (who by now dominated even the trade of the capital city itself), and the King of Naples, gave Byzantium little respite. One emperor desperately accepted papal primacy and reunion with the Roman Church; this policy did little except antagonize his own clergy and his successor abandoned it. Religion still divided Christendom.

As the fourteenth century wore on, the Byzantines had a deepening sense of isolation. They felt abandoned to the infidel. An attempt to use western mercenaries from Catalonia only led to their attacking Constantinople and setting up yet another breakaway state, the Catalan duchy of Athens, in 1311. Occasional victories when an island or a province was retaken did not offset the general tendency of these events, nor the debilitating effect of occasional civil war within the empire. True to their traditions, the Greeks managed even in this extremity to invest some of these struggles with a theological dimension. On top of all this, the plague in 1347 wiped out a third of what was left of the empire’s population.

In 1400, when the emperor travelled the courts of western Europe to drum up help (a little money was all he got) he ruled only Constantinople, Salonica and the Morea. Many in the West now spoke of him, significantly, as ‘emperor of the Greeks’, forgetting he was still titular emperor of the Romans. The Turks surrounded the capital on all sides, and had already carried out their first attack on it. There was a second in 1422. John VIII made a last attempt to overcome the strongest barrier to cooperation with the West. He went in 1439 to an ecumenical council sitting in Florence and there accepted papal primacy and union with Rome. Western Christendom rejoiced; the bells were rung in all the parish churches of England. But the Orthodox East scowled. The council’s formula ran headlong against its tradition; too much stood in the way – papal authority, the equality of bishops, ritual and doctrine. The most influential Greek clergy had refused to attend the council; the large number who did all signed the formula of union except one (he, significantly, was later canonized) but many of them recanted when they went home. ‘Better,’ said one Byzantine dignitary, ‘to see in the city the power of the Turkish turban than that of the Latin tiara.’ Submission to the pope was for most Greeks a renegade act; they were denying the true Church, whose tradition Orthodoxy had conserved. In Constantinople itself priests known to accept the council were shunned; the emperors were loyal to the agreement but thirteen years passed before they dared to proclaim the union publicly at Constantinople. The only benefit from the submission was the pope’s support for a last crusade (which ended in disaster in 1441). In the end the West and East could not make common cause. The infidel was, as yet, battering only at the West’s outermost defences. French and Germans were absorbed in their own affairs; Venice and Genoa saw their interest might lie as much in conciliation of the Turk as in opposition to him. Even the Russians, harried by Tatars, could do little to help Byzantium, cut off as they were from direct contact with her. The imperial city, and little else, was left alone and divided within itself to face the Ottomans’ final effort.