The Next Decade (29 page)

Singapore is now an independent city-state, enormously prosperous because of its geographical position and because of its technology industry. It needs the United States as a customer, but also to protect its sovereignty. When Malaya was given independence, the primarily ethnic-Chinese Singapore split from the predominantly Muslim Malaysia. Relations have varied, and there has not been much threat of annexation, but Singapore understands two geopolitical realities: that the worst thing in the world is to be rich and weak, and that security is never a sure thing. What Malaysia or, for that matter, Indonesia might want to do in a generation or two can’t be predicted.

The United States cannot simply control Singapore; instead it must have cooperative relations with it. As in his dealings with Korea and Australia, the president should be more generous with Singapore than he needs to be in order to assure the alliance. The price is small and the stakes are very high.

Indonesian Sea-Lanes

INDIA

It is in the context of the western Pacific that we should consider India. Despite its size, its growing economy, and the constant discussion of India as the next China, I simply do not see India as a significant player with deep power in the coming decade. In many ways, India can be understood as a very large Australia. Both countries are economically powerful—obviously in different ways—and in that sense they have to be taken quite seriously.

Like Australia, India is a subcontinent isolated geographically, although Australia’s isolation, based on thousands of miles of water, is much more visible. But India is in its own way an island, surrounded by land barriers perhaps less easily passable than oceans. The Himalayas block access from the north, and hilly jungles from the east. To the south, it is surrounded by the Indian Ocean, which is dominated by the United States Navy.

The biggest problem for India lies to the west, where there is desert, and Pakistan. That Islamic nation has fought multiple wars with the predominantly Hindu India, and relations range from extremely cool to hostile. As we saw in my discussion of Afghanistan, the balance of power between Pakistan and India is the major feature of the subcontinent. Maintaining this balance of power is a significant objective for the United States in the decade to come.

India is called the democratic China, which, to the extent that it is true, exacts a toll in regional power. One of the great limitations on Indian economic growth, impressive as it has been, is that while India has a national government, each of its constituent states has its own regulations, and some of these prevent economic development. These states jealously guard their rights, and the leadership guards its prerogatives. There are many ways in which these regions are bound together, but the ultimate guarantor is the army.

India maintains a substantial military that has three functions. First, it balances Pakistan. Second, it protects the northern frontier against a Chinese incursion (which the terrain makes difficult to imagine). Most important, the Indian military, like the Chinese military, guarantees the internal security of the nation—no minor consideration in a diverse country with deeply divided regions. There is currently a significant rebellion by Maoists in the east, for instance, just the sort of thing that it is the army’s job to prevent or suppress.

On the seas, the Indians have been interested in developing a navy that could become a major player in the Indian Ocean, protecting India’s sea-lanes and projecting Indian power. But the United States has no interest in seeing India proceed along these lines. The Indian Ocean is the passageway to the Pacific for Persian Gulf oil, and the United States will deploy powerful forces there no matter how it reduces its presence on land.

To keep Indian naval development below a threshold that could threaten U.S. interests, the United States will strive to divert India’s defense expenditure toward the army and the tactical air force rather than the navy. The cheapest way to accomplish this and preempt a potential long-range problem is for the United States to support a stronger Pakistan, thus keeping India’s security planners focused on the land and not the sea.

By the same token, India is interested in undermining the U.S.-Pakistani relationship or, at the very least, keeping the United States in Afghanistan in order to destabilize Pakistan. Failing that, India may reach out to other countries, as it did to the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Pakistan does not represent an existential threat to India, even in the unlikely event of a nuclear exchange. But Pakistan is not going to simply collapse, and therefore will remain the persistent problem that India’s strategic policy will continue to pivot on.

India lags behind China in its economic development, which is why it is not yet facing China’s difficulties. The next decade will see India surging ahead economically, but economic power by itself does not translate into national security. Nor does it translate into the kind of power that can dominate the Indian Ocean. American interests are not served by making India feel overly secure. Therefore, U.S.-Indian relations will deteriorate over the next ten years, even as the United States leaves Afghanistan and even as U.S.-Indian trade continues.

THE ASIAN GAME

In the decade to come, while the United States is preoccupied with other issues, the two major Asian powers, China and Japan, will be only minimally subject to outside influence. They will move as their internal processes dictate. Given that pace, the United States should not invest heavily in managing the Chinese-Japanese relationship. To the extent possible, the United States should help maintain a stable China and work to maintain its relationship with Japan.

Nonetheless, the peace of the western Pacific will not hold together indefinitely, and the United States should work to cement strong relations with three key players: Korea, Australia, and Singapore.

These three countries would prove essential allies in the event of war with any western Pacific country, particularly Japan, and preparations cannot begin too soon. Building the Korean navy, creating facilities in Australia, and modernizing Singapore’s forces will not arouse great anxiety. These are steps that, taken in this decade, will create the framework for managing any conflict that might arise.

CHAPTER 11

A SECURE HEMISPHERE

G

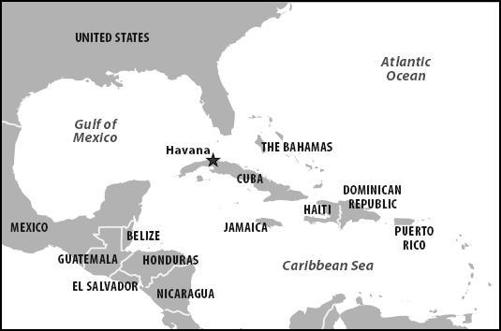

iven that the United States shares a hemisphere and quite a bit of history with Latin America and Canada, some might assume that this region has a singular importance for the U.S. Indeed, many Latin Americans in particular see the United States as obsessed with dominating them, or at least obtaining their resources. But with few exceptions—primarily in the case of Mexico and Cuba—what happens in Latin America is of marginal importance to the United States, and the region has rarely held a significant place in American thinking. Part of this has to do with distance. Washington is about a thousand miles farther from Rio de Janeiro than it is from Paris. And unlike European and Asian powers, the United States has never had an extensive war with the Latin world south of Panama. This isn’t to say that there isn’t mutual distrust and occasional hostility. But in the end—and again excepting Mexico and Cuba—the fundamental interests of the United States simply don’t intersect with those of Latin America.

The United States has had limited concern with the region in part because of the fragmentation there, which has prevented the rise of a transcontinental power. South America looks like a single geographical entity, but in fact the continent is divided by significant topographic barriers. First, running north and south are the Andes, a chain of mountains much taller than the Rockies or the Alps and with few readily traversable passes. Then, in the center of the continent, the vast Amazonian jungle presents an equally impenetrable barrier.

There are actually three distinct regions in South America, each cut off from the others to the extent that basic overland commerce is difficult and political unity impossible. Brazil is an arc along the Atlantic Coast, with the inhospitable Amazon as its interior. A separate region lies to the south of Brazil along the Atlantic, and it consists of Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay, the latter not on the coast but part of this bloc of nations. To the west are the Andean nations of Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela. Off the mainland and not completely Latin are, of course, the Caribbean islands, important as platforms but without weight themselves.

The only connection between Brazil and the southern nations is a fairly narrow land bridge through Uruguay. The Andean nations are united only in the sense that they all share impenetrable geographies. The southern region along the Atlantic could become integrated, but there is really only one significant country there, Argentina. In addition, there is no passable land bridge between North and South America because of Central America’s jungle terrain, and even if there were a bridge, only Colombia and perhaps Venezuela could take advantage of it.

The key to American policy in Latin America has always been that for the United States to become concerned, two elements would have to converge: a strategically significant area (of which there are few in the region) would have to be in the hands of a power able to use it to pose a threat. The Monroe Doctrine was proclaimed in order to make it clear that just such an eventuality was the single unacceptable geopolitical development as far as the United States was concerned.

During World War II, the presence of German agents and sympathizers in South America became a serious issue among strategists in Washington, who envisioned German troops arriving in Brazil from Dakar, across the Atlantic. Similarly, during the Cold War, the United States became genuinely concerned about Soviet influence in the region and intervened on occasion to block it. But neither the Germans nor the Soviets made a serious strategic effort to dominate South America, because they understood that in most senses the continent was irrelevant to U.S. interests. Instead, their efforts were designed merely to irritate Washington and divert American resources.

Terrain Barriers in South America

The one place where outside involvement has been seen as a threat to be taken seriously is Cuba, and its singular importance is based on its singularly strategic location.