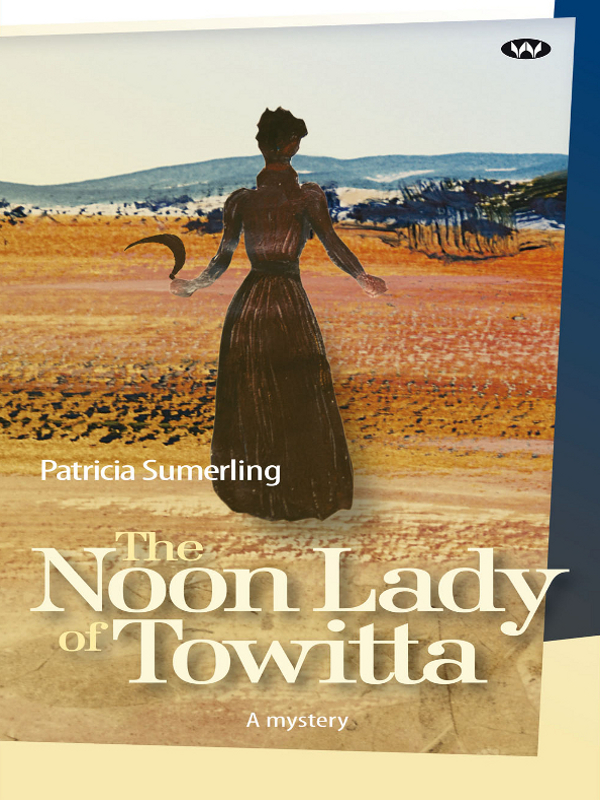

The Noon Lady of Towitta

The Noon Lady of Towitta

Patricia Sumerling is an Adelaide-based professional historian who believes some of the unresolved tales she comes across in her work are ripe for unravelling and for imaginative reconstruction as distinctively South Australian stories.

The Noon Lady

of Towitta

Patricia Sumerling

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2010

This edition published 2011

Copyright © Patricia Sumerling 2010

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission.

Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover designed by Mark Thomas

Edited by Julia Beaven

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

| Author: | Sumerling, Patricia, 1945â . |

| Title: | The noon lady of Towitta/Patricia Sumerling. |

| ISBN: | 978 1 86254 982 1 (epub). |

| Subjects: | Schippan, Bertha â Fiction. |

| Â | Schippan, Maria Augusta. 1878â1919. â Fiction. |

| Â | Murder â South Australia â Towitta â Fiction. |

| Â | Trials (Murder) â South Australia â Towitta â Fiction. |

| Dewey Number:Â Â Â | A823.4 |

for

Roger Andre,

who made this novel possible

Contents

2 January 1902

Detective Bill Priest was urgently recalled to duty on the second day of the new year as the city of Adelaide took refuge from the holiday heat. A telegram had arrived at police headquarters: a girl had been brutally murdered near Towitta, at the Schippan family farm.

âWhere the hell is Towitta?' Priest asked Sergeant Decker.

âWell, the telegram came from Truro, so it must be somewhere round there. Sedan's near there too. The place is full of German families on farms.'

Priest and a large company of troopers prepared to travel to the murder scene and later that day boarded the train at North Adelaide for Freeling near the Barossa Valley. Extensive equipment and stores were needed for what could be many hot, windy days in the middle of nowhere. After settling the numerous horses, wagons and stores in the cattle trucks, they took their places in the passenger carriage set aside for them. On the journey north, Priest pondered the name Schippan. It was not a common name but he'd been involved with several cases where it had cropped up. He remembered a domestic servant named Mary Schippan whose friend had died after an illegal operation while working for a well-to-do city family a couple of years earlier. He had had trouble in convicting the well-known Adelaide abortionist responsible for several other botched cases. When he finally managed to obtain corroborative evidence he was able to have her locked away for several years. It had been difficult to find any woman who would tell on her, so popular were her services in Adelaide. He'd have been happy to see her hang for the several deaths she was responsible for. He recalled that she'd have been headed for the gallows but for an unfortunate technicality in the law that meant she got off with her life. He smiled as he pictured her behind bars.

The name Schippan also featured in a case near Sedan where a tyrannical German farmer named Mathes Schippan was involved in a shooting several years before but was acquitted by the courts in Adelaide. There were other disturbing allegations about him that couldn't be proven. One case was the murder of a hawker near Sedan. For some reason Schippan was not arrested although he was under suspicion. Priest soon learned that Mary, the servant involved in the abortion case, was Mathes Schippan's daughter. Considering this German farmer had been involved in several acts of violence, as was his daughter to some degree, Priest kept an open mind about what he might find at the farm. He kept his thoughts to himself about what he already knew of the Schippans while he became familiar with the intricacies of the Towitta murder.

Priest thought it ironic that in the first brief mention of the murder in the newspapers, the journos labelled it âthe Towitta Tragedy'. There was no tragedy about it as far as he was concerned. It was a brutal, savage killing, where the victim, a young girl, was butchered like an animal. Her throat had been repeatedly slashed from ear to ear and she was stabbed at least forty times in a frenzy by someone who knew how to use a knife. No, it was hardly a tragedy.

After many years on the job, Priest had come to learn that nothing was what it seemed and it made no sense to jump to conclusions. To do so would make it harder to find a new theory should the first one not stand up to scrutiny. Priest had been looking forward to a challenge such as this, for over the last few months he'd been involved in some pretty mundane cases. He had been following the sensation in South Africa where Australian soldiers were being tried for killing a Boer priest in cold blood.

The murder scene at Towitta was two days' travel by horse from Adelaide. Taking the train from Adelaide to Freeling and then travelling by horse through Angaston to Towitta cut the journey by half. On arrival at Towitta it was his responsibility to see that his band of troopers was sent around the district to find suitable places to board, while others camped in tents at the farm. It was also his task to organise the investigations and inquest. Priest planned the gathering of evidence and compiling of reports like a military operation. He had to ensure that no stone or speck of dust was left unturned in finding out what had taken place.

Priest and his men broke their journey overnight at the police station at Angaston.

âWhat's the gen?' Priest asked the two local constables on duty.

The older one, Constable Beckmann replied. âWell, word is an unaccountable man was alleged to have broken into a farmhouse late at night and for no reason cut a girl's throat from ear to ear. It was surrounded by a lot of mystery and a great deal more running for assistance than running at the alleged intruder.'

âReally?'

âYes, really, so the search is for some shadowy person who broke in, didn't steal anything and didn't even bring his own knife with him to do the horrible deed?'

Priest butted in, âA straightforward case then?'

âIf only. And to wrap it up nice and neat he left no footprints and was seen by nobody as he fled the area.'

Priest asked, âWhat about the rest of the family?'

âAs far as we have been informed the girl's elder sister, Mary, was able to struggle free with minor cuts and raise the alarm by running to the barn where her two brothers slept. They won't be much help, I believe they're rather simple. She then sent one of them to their closest neighbours for help. Apparently, there were two older brothers but they left home a couple of years ago after bashing up their father. Revenge, according to local gossip, for years of beatings and whippings.'

âWho on earth would have been wandering around in the middle of a hot night in the middle of nowhere?' Priest asked.

âSir, the district is rife with gossip about the Schippan family. There is a lot being said about old man Schippan â he was a tricky character when crossed, I believe.'

Priest nodded. âI remember a case six or so years ago when Schippan shot a youth. Hartwig, I think his name was, a real troublemaker. Old Schippan claimed he shot him accidentally.'

Constable Beckmann said, âWe also know now that the two sisters and their brothers were on their own. Their parents had left the farm two days after Christmas to spend time with relatives at Eden Valley. We've already had locals popping in here to try and find out more. There's lots of talk about the fact the two single young women were left on their own with two simple brothers.'

âI wonder whether any local man, such as a sweetheart, would have known that they were on their own?' asked Priest.

âIt could well have been a stranger passing through, a hawker or commercial traveller up to no good. Although the chances of this seem unlikely, don't you think?' Constable Campbell replied.

The older constable coughed and waited until all eyes were on him before announcing: âIt seems that Mary Schippan has said that the intruder had an English-sounding voice when he threatened to kill her.'

âHmmm, I can see we'll be having to do a door-to-door on this around the district, especially as there are so many opinions and gossip about the family.' Priest glanced at the darkening sky and his men making camp in the police yard. âWe have an early start. I'll go and join my men now.'

Priest and the mounted troopers rose before dawn the next morning and made their way through Angaston and down the treacherous Parrot Hill to the Murray Plains twenty-five miles away. He surveyed the plains from the top of the hill, drought ravaged and the colour of a desert. The sand drifts glinted red and released spirals of dust when the wind blew. This was Priest's first visit to the area for some time and he was alarmed at just how desperate the conditions really were. While he was thanking his lucky stars that he didn't live down there himself, he remembered the staff at the police station in Angaston telling him the Murray Flat farmers were better off than many others because they at least had the luxury of rabbits for food.

Priest pondered if that would make much difference. The little township of Towitta must have suffered a miserable existence due to the punishing drought conditions. It was no wonder that someone's nerve had given way in such a desolate place. Looking down the hill to the small scattered farms in that burning South Australian heat, he wondered how often it happened that a peaceful township became notorious overnight due to an act of murder.

Once at the tiny township of Towitta, Priest discovered that the population that used the scattered group of buildings, including a post office, a school, chapel and store, totalled seventy people living in just fifteen houses. The district was made up of many small farms covering around 200 acres each. Sedan, not quite seven miles away, was mostly settled by German families and Angaston was twenty-five miles away up steep and treacherous hill roads. Thirty years before, the Germans in the region had spilled over onto the plains from the more fertile valley of the Barossa, their heartland and spiritual centre.