The Norm Chronicles (38 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Mammography is quite good as screening tests go, as it correctly classifies 90 per cent of cases, but because only around 10 in every 1,000 women screened have breast cancer, most of the positive results are in people who don’t have it: false alarms. It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack, when a lot of the hay looks like needles, and explains why the vast majority of people who set off airport security alerts are innocent.

Of course, maybe delaying some passengers, giving some anxiety to women and locking up some suspicious-looking people may be a price worth paying. But this is not the only problem with screening tests.

2

Next, there is the possible harm of the test itself. If we believe the linear no-threshold principle for radiation damage (see

Chapter 19

), then we can estimate the harm done by imaging healthy people. We’ve seen that CT scans are estimated to cause thousands of cancers, but most of these will presumably be for some diagnostic purpose. Airport scanning is more controversial, and each ‘backscatter‘ X-ray is limited to 0.1 micro-Sieverts (1 banana). This is only equivalent to a few minutes of background radiation, and is around 1 per cent of the exposure from a five-hour flight itself. A frequent flyer who had 4,000 of these scans would be exposed to radiation equivalent to 1 mammogram, and if we really believe the LNT principle then 100 million frequent flyers would end up with 6 cancers caused by the scanning, as part of the 40 million cancers they would get anyway.

3

The radiation harms of mammography have been estimated as follows: the NHS Cancer Screening Programme reports that if 14,000 women are screened for 10 years (3 mammograms), around 1 fatal cancer will be caused.

4

If we assume each fatal cancer costs a woman 20 years of life, then that is around 8 MicroLives per mammography, around 16 cigarettes, exactly the figure we arrived at in

Chapter 19

, when discussing radiation.

A recent US study puts the risk somewhat lower, estimating that if 100,000 women are screened every other year between the ages of 50 and 59, this will lead to 14 cancers and 2 deaths, although the recommended US screening regime would lead to 86 cancers and 11 deaths.

5

But the main problem with medical screening is what is called over-diagnosis, or harm done by medical care itself.

6

It’s a simple idea: things are treated that would never have been a problem anyway.

This is the problem that preoccupies Prudence, recently quantified by an independent report in the UK, which reported that for every woman whose early death from breast cancer was saved by screening, three women were given full treatment for a breast cancer that would never have bothered them if they hadn’t gone along to screening.

7

The curative screening story we told at the beginning was entirely about events, about the bad things that happen and how medicine can save us (see

Chapter 4

, on non-events). But it is a story that can go

wrong, both in detection of the bad events and by sounding false alarms over non-events, and also even by causing bad events. People who pass through the system follow many different paths and have many different stories, as

Figure 30

shows.

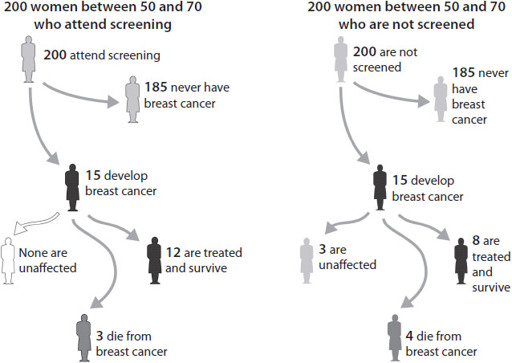

Figure 30:

What might be expected for 250 women who either do or do not attend breast screening every three years between ages 50 and 70, and then following them up until aged 80

Fifteen will get breast cancer and, if screened, all will be treated, although three will die of their breast cancer. One of the survivors owes her life to the screening, but three other survivors would never have been bothered by their cancer if they had not gone to screening – ‘over-treated’ cases. Data adapted from Cancer Research UK.

8

So although Prudence wants reassurance, and screening looks like the way to get it, it is in some ways back to the classic problem with risk: it tries to define the individual using probabilities, and these are not certain for you. You will never know which group you are in – whether you benefited from screening or were harmed by it. Screening can help narrow the odds, one way or another, but even relatively accurate screening seldom rules fatal risk out, or in, ever. Norm is right, sadly; we have no choice but to accept uncertainty even if that means more fear.

Prostate cancer is another classic example. The Prostate Specific

Antigen (PSA) test, based on work by Richard Ablin in the 1970s, is used extensively in the US for screening men without symptoms. Ablin now says that PSA testing is ‘a profit-driven public health disaster’.

9

Nevertheless, in the UK Andrew Lloyd Webber argued in the House of Lords that ‘all men over 50 should have the PSA test and GPs should be encouraged to encourage them to do so’.

10

How can such a remarkable difference in opinion arise?

The problem is that, if you have no symptoms or other reasons to be at increased risk, this simple test can start you on a treatment regime ending in incontinence and impotence, as Lloyd Webber has honestly acknowledged.

11

It is not difficult to find stories from people who claim their lives were saved by being screened, but it is, however, difficult to say what would have happened if they had

not

been screened. Maybe they would never have been hurt by whatever was found. It is extraordinary how much hidden disease there is, sitting around not causing any problems. When 2,000 healthy people with an average age of 63 had their brains scanned as part of a research project, 145 (7 per cent) had had brain infarcts (strokes) that they had not noticed, while 31 (1.6 per cent) had non-cancerous brain tumours. In people over 40 receiving diagnostic ultrasound, 14 per cent of men and 11 per cent of women were found to have gallstones, even though they had no symptoms.

12

Studies at autopsy for deaths unrelated to any disease – in car accidents, say – reveal the astonishing amount of undetected cancer. In fact, there’s around a 50:50 chance that DS has prostate cancer at the moment and MB will have too, very shortly, since ‘it is estimated from post-mortem data that around half of all men in their fifties have histological evidence of cancer in the prostate, which rises to 80% by age 80’, says Cancer Research UK, although it goes on to point out that ‘only 1 in 26 men (3.8%) will die from this disease’.

13

Unfortunately, screening can’t tell the difference between cancers that will turn nasty and those that will sit around minding their own business. Over the last 30 years the US has experienced a large jump in the number of prostate cancers diagnosed, but there has been only a moderate impact on the death rate, even with great improvements in

treatment, suggesting the screening has not been of substantial benefit in reducing deaths.

14

But all this activity makes the ‘survival’ rates look wonderful, as survival is measured from diagnosis, and so the start-time for ‘five-year survival’ begins earlier, even if people are not living longer. By adding cases that would never have been noticed without screening, the survival statistics appear even better.

Working out the balance between the benefits and harms of screening is notoriously tricky, and the best way is through large trials in which thousands of people are randomly allocated to be offered screening or not. In the US, 80,000 men were divided up in this way, and after 13 years the screened group had 12 per cent more cancers diagnosed but no difference in deaths from prostate cancer.

15

A European study of 182,000 men did find a 21 per cent reduction in prostate-cancer deaths after 11 years in the group offered screening, corresponding to a reduction of 1 death per 1,000 men, so that 1,055 men would need to be offered screening and 37 additional cases treated to prevent 1 death from prostate cancer. But there was no effect on deaths from all causes.

16

It is very natural for those who have endured diagnosis and treatment for cancer to attribute their survival to the test that first alerted them to their illness. So it is a potentially upsetting message that, of survivors of cancer found at screening, 90 per cent would be alive had they not gone to screening in the first place.

17

People’s innate storytelling habit is to connect one event with a preceding one: first this (screening), then that (treatment), leading happily ever after to survival. Not necessarily.

But if not in screening, can we find certainty in our genes? To check this, DS spat into a plastic tube and sent it across to the US, so that a company called

23andMe

could check (screen) some markers in his DNA and tell him whether he could blame his ancestors for his prospects.

18

But they only provided lots of information about all the horrible things that he

might

develop, including telling him he had an increased lifetime risk of type-2 diabetes, which they did using the graphic in

Figure 31

. Will he end up being a figure in white or black? Well, he has already lived to 59 and not got diabetes yet, so it’s looking hopeful he might be one of the white ones. These are just assessments of the risks

using a few items of information abut his genetic make-up that could have been obtained when DS was a baby. Now things have changed, and so the odds have too.

Figure 31:

DS’s risk of type-2 diabetes, based on some genetic markers

To find out whether he had a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, DS had to tick a box agreeing that he really,

really

wanted to know this information before it would be unlocked. Which he did. And the answer was? He isn’t telling.

So is this the future? And how much anxiety, investigation and unnecessary medical care will it bring? Because if it’s a future that chases reassurance, it might in a vast number of cases simply remind us, perhaps painfully, how much we will never know.

25

MONEY

I

N THE DREAM

Norm was by the sea again with his little brother, digging a hole in the sand just like they did on that endless beach at Skegness. He liked it outside, liked the sea and the air. It was the time Dad bought them those red metal spades with wooden shafts and handles. The spades were ace, they said, ace. He gave them money for ice creams too. Norm felt the coins in the pocket of his shorts. He liked that: the roundness, the promise.

The sand was firm and just wet enough to stay up as they carved the sides of the hole, steep and square. Their arms dug, turned and tipped. They liked how the sand gave way to the spade, how it cut in slabs. Then Norm’s brother began another hole. Now there were two holes with a wall between them two feet wide. They cut foot holes in the sides to climb out.

‘A tunnel,’ said the little brother.

‘Yeah, a tunnel,’ said Norm, ‘sort of.’

Carving slices of sand, they joined their two holes with a tunnel. They widened the tunnel and widened it some more, slice by-slice, with their red spades, squatting and cutting, watching for cracks in case it was going to fall. And when it was done they were glad and had two holes nearly as deep as the boys were tall. There was a bridge of solid sand, the tunnel perhaps two feet high.

‘Crikey,’ said Dad, who came over with trousers rolled up, ‘can you get through?’

Norm’s brother jumped in with a sandy thud, twisted onto his hands and knees. He was little. He squeezed through the tunnel and up the other side.

‘Easy,’ he said.