The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (10 page)

How heinous had the fact been, how deserving

Contempt, and scorn of all to be excluded

M

ILTON,

14

Samson Agonistes

Our Brethren, are from

Thames

to

Tweed

departed,

And of our Sisters, all the kinder hearted,

To

Edenborough

gone, or Coacht, or Carted.

D

RYDEN:

‘Prologue to the University of Oxford’

What can enable sots, or slaves or cowards?

Alas! not all the blood of all the HOWARDS.

P

OPE:

15

Essay on Man

It gives to think that our immortal being…

W

ORDSWORTH:

16

The Prelude

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever

Its loveliness increases: it will never

Pass into nothingness;

K

EATS:

Endymion

, Book One

And like the flowers beside them, chill and shiver,

R

OBERT

F

ROST:

‘Spring Pools’

With guarded unconcerned acceleration

S

EAMUS

H

EANEY:

‘From the Frontier of Writing’

There’s far too much encouragement for poets–

W

ENDY

C

OPE:

‘Engineers’ Corner’

Substitutions

I hope you can see that the feminine ending is by no means the mark of imperfect iambic pentameter. Let us return to Macbeth, who is

still

unsure whether or not he should stab King Duncan:

To prick the sides of my intent, but only

Vault

ing ambition, which o’erleaps itself

And falls on th’ other.–How now! what news?

We have cleared up the first variation in this selection of three lines, the weak or unstressed ending. But what about this ‘vault

ing

ambition’ problem? Keats has done it too, look, at the continuation to his opening to

Endymion

:

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever

Its loveliness increases: it will never

Pass

into

noth

ing

ness

; but

still

will

keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full

of sweet

dreams

, and

health

, and

qui

et

breath

ing

The first feet of lines 3 and 5 are ‘inverted iambs’ or

trochees

. What Keats and Shakespeare have employed here is sometimes called

trochaic substitution

, a technique, like weak endings, too common to be considered a deviation from the iambic norm. It is mostly found, as in the above instances and the following, in the

first foot

of a line. You could call it a trochaic substitution, or the

inversion

of an iamb–it amounts to the same thing.

Mix’d

in each other’s arms, and heart in heart,

B

YRON:

Don Juan

, Canto IV, XXVII

Well

have ye judged, well ended long debate,

Synod of gods, and like to what ye are,

M

ILTON:

Paradise Lost

, Book II

Far

from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife

G

RAY:

‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’

Shall

I compare thee to a summer’s day?

S

HAKESPEARE:

Sonnet 18

That’s an interesting one, the last. Shakespeare’s famous sonnet opens in a way that allows different emphases. Is it

Shall

I compare thee, Shall

I

compare thee or

Shall I

compare thee? The last would be a

spondaic substitution

. You remember the spondee, two equally stressed beats?

17

What do you feel? How would you read it out? There’s no right or wrong answer.

Trochaic substitution of an

interior

foot is certainly not uncommon either. Let’s return to the opening of Hamlet’s great soliloquy:

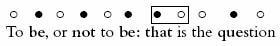

Here, the fourth foot can certainly be said to be trochaic. It is helped, as most interior trochaic switches are, by the very definite caesura, marked here by the colon. The pause after the opening statement splits the line into two and allows the trochaic substitution to have the effect they usually achieve at the beginning of a line. Without that caesura at the end of the preceding foot, interior trochaic substitutions can be cumbersome.

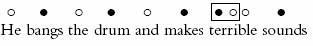

That’s not a very successful line, frankly it reads as prose: even with the ‘and’ where it is, the instinct in reading it as verse is to make the caesural pause after ‘makes’–this resolves the rhythm for us. We don’t mind starting a phrase with a trochee, but it sounds all wrong inserted into a full flow of iambs.

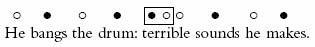

That’s better: the colon gives a natural caesura with which to split the line allowing us to start the new thought with a trochee.

For this reason, you will find that

initial

trochaic substitution (i.e. that of the first foot) is by far the most common.

Mil

ton! Thou shouldst be living at this hour:

Eng

land hath need of thee: she is a fen

W

ORDSWORTH:

‘Milton!’

Seas

on of mists and mellow fruitfulness!

K

EATS:

‘Ode to Autumn’

Just as it would be a pointless limitation to disallow

unstressed endings

to a line, so it would be to forbid

stressed beginnings

. Hence trochaic substitution.

There’s one more inversion to look at before our heads burst.

Often in a line of iambic pentameter you might come across a line like this, from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 1:

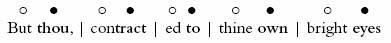

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes

How would you scan it?

‘Contracted

to

thine own bright eyes’ is rather ugly, don’t we think? After all there’s no valuable distinction of meaning derived by hitting that innocent little particle. So has Shakespeare, by only the fifth line of his great sonnet sequence already blown it and mucked up his iambic pentameters?

Well no. Let’s scan it like this: 18

18

That third foot is now

pyrrhic

, two

unaccented

beats: we’ve taken the usual stress off its second element, we have ‘demoted’ the foot, if you like. We have, in metrical jargon, effected

pyrrhic substitution

.

This is most likely to occur in the third or fourth foot of a line, otherwise it disrupts the primary rhythm too much. It is essential too, in order for the metre to keep its pulse, that the pyrrhic foot be followed by a proper iamb. Pyrrhic substitution results, as you can see above, in

three

unaccented beats in a row, which are resolved by the next accent (in this case

own

).

Check what I’m saying by flicking your eyes up and reading out loud. It can all seem a bit bewildering as I bombard you with references to the third foot and the second unit and so on, but so long as you keep checking and reading it out (writing it down yourself too, if it helps) you can keep track of it all and

IT IS WORTH DOING

.