The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (8 page)

At Keswick, and, ¶ through still continued fusion

Of one another’s minds, ¶ at last have grown

To deem as a most logical conclusion,

That Poesy has wreaths for you alone:

There is a narrowness in such a notion,

Which makes me wish you’d change your lakes for ocean.

I am sure you have now got the point that pausing and running on are an invaluable adjunct to the basic pentametric line. I have taken a long time over this because I think these two devices exemplify the crucial point that

ADHERENCE TO METRE DOES NOT MILITATE AGAINST NATURALNESS

. Indeed it is one of the paradoxes of art that structure, form and convention

liberate

the artist, whereas openness and complete freedom can be seen as a kind of tyranny. Mankind can live free in a society hemmed in by laws, but we have yet to find a historical example of mankind living free in lawless anarchy. As Auden suggested in his analogy of Robinson Crusoe,

some

poets might be able to live outside convention and rules, but most of us make a hash of it.

It is time to try your own. This exercise really is fun: don’t be scared off by its conditions: I’ll take you through it all myself to show you what is required and how simple it is.

Poetry Exercise 3

- Write five pairs of

blank

(non-rhyming) iambic pentameter in which the first line of each pair is end-stopped and there are no caesuras. - Now write five pairs with (give or take)

the same meaning

in which there

is

enjambment. - Make sure that each new pair also contains at least two caesuras.

- This may take a little longer than the first writing exercise, but no more than forty-five minutes. Again, it is not about quality.

To make it easier I will give you a specific subject for all five pairs.

- 1. Precisely what you see and hear outside your window.

- 2. Precisely what you’d like to eat, right this minute.

- 3. Precisely what you last remember dreaming about.

- 4. Precisely what uncompleted chores are niggling at you.

- 5. Precisely what you hate about your body.

Once again I have had a pitiful go myself to give you an idea of what I mean.

W

ITHOUT

caesura or enjambment:

1 Outside the Window

I hear the traffic passing by my house,

While overhead the blackbirds build their nests.

2 What I’d Like to Eat

I’d really like some biscuits I can dunk,

Unsalted crisps would fill a gap as well.

3 A Recent Dream

I dreamt an airport man had lost my bags

And all my trousers ended up in Spain.

4 Pesky Tasks Overdue

I need to tidy up my papers now

And several ashtrays overflow with butts.

5 My Body

Too many chins and such a crooked nose,

Long flabby legs and rather stupid hair.

With caesura and enjambment:

1 Outside the Window

The song of cars, so like the roar the sea

Can sing, has drowned the nesting blackbirds’ call.

2 What I’d Like to Eat

Some biscuits, dunked–but quick in sudden stabs

Like beaks. Oh, crisps as well. Unsalted, please.

3 A Recent Dream

Security buffoons, you sent my strides

To Spain, and all my bags to God knows where.

4 Pesky Tasks Overdue

My papers seethe. Now all my writing desk

Erupts. Volcanic mountains cough their ash.

5 My Body

Three flobbing chins are bad, but worse, a bent

And foolish nose. Long legs, fat thighs, mad hair.

These are only a guide. Go between each Before and After I have composed and see what I did to enforce the rules. Then pick up your pencil and pad and have a go yourself.

Use the same titles for your couplets that I did for mine. The key is to find a way of breaking the line, then running on to make the enjambment. It doesn’t have to be elegant, sensible or clever, mine aren’t, though I will say that the very nature of the exercise forces you, whether you intend it or not, to

concentrate

the sense and movement of the phrasing in a way that at least gestures towards that distillation and compactness that marks out real poetry. Here’s your blank space.

Weak Endings, Trochaic and Pyrrhic Substitutions

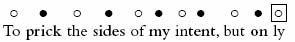

Let us now return to Macbeth, who is still considering whether or not he should kill Duncan. He says out loud, as indeed do you: ‘I have no spur…

To prick the sides of my intent, but only

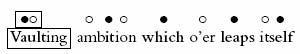

Vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself

And falls on th’ other.–How now! what news?

Forgetting caesuras and enjambments this time, have a look at the three lines as an example of iambic pentameter. Get that pencil out and try marking each accented and unaccented syllable.

Eleven

syllables! There’s a rogue extra syllable at the end of line 1, isn’t there? An unstressed orphan bringing up the rear. The line scans like this:

There is more: the

next

line doesn’t start with an iamb at all! Unless the actor playing Macbeth says ‘vault

ing

ambition’ the line goes…

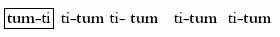

The mighty Shakespeare deviating from metre? He is starting an iambic line with a

tum

-ti, a

trochee

.

Actually, in both cases he is employing two

variations

that are so common and necessary to lively iambic verse that they are not unusual enough even to call deviations.

We will attend to that

opening trochaic foot

in a moment. Let us first examine this orphan or ‘rogue’ unaccented syllable at the end of the line. It makes the line eleven syllables long or

hendecasyllabic

.

It results in what is called a

weak

or

feminine

ending (I hope my female readers won’t be offended by this. Blame the French, we inherited the term from them. I shall try not to use it often). Think of the most famous iambic pentameter of all:

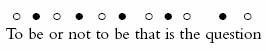

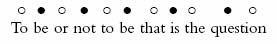

To be or not to be that is the question

Count the syllables and mark the accents. It does the same thing (‘question’ by the way is

disyllabic

, two syllables, any actor who said

quest

-i-

on

would be laughed off the stage and out of Equity. It is certainly

kwestch n

n

11

).

11