The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (7 page)

Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

go who wish to go, and do no harm to me or mine.”9 Once

you have issued this invitation, I would advise you not to address the elves directly.

You don’t know how far some of them may have come

in space or time, so it’s a good idea to turn off the television and most electric lights which the oldest of the com-

pany may find glaring. If you have a fireplace, make a fire.

Otherwise, light plenty of candles. Set the table with your best dishes but offer simple foods: bread, meat, milk. If you are very lucky, you will get some dísir along with the Álfar.

These ladies may be expecting a reddened altar, so now

would be the time to bring out that blood red Christmas

tablecloth or runner. Feel free to talk and laugh with any living company—it’s a party, after all—but keep in mind

that it is all done in honor of the elves. Don’t be a Hovian; leave the door ajar for the duration of the feast, and don’t be surprised if you see a few familiar faces shining out from the shadows.

9. These words are spoken by the Cinderel a figure in “The Sisters and the Elves” on page 55 of Jacqueline Simpson’s

Icelandic Folktales and Legends

. In the West Fjords of Iceland, it was customary to speak such formulae at either Christmas or New Year’s Eve.

46 At Home with the Elves

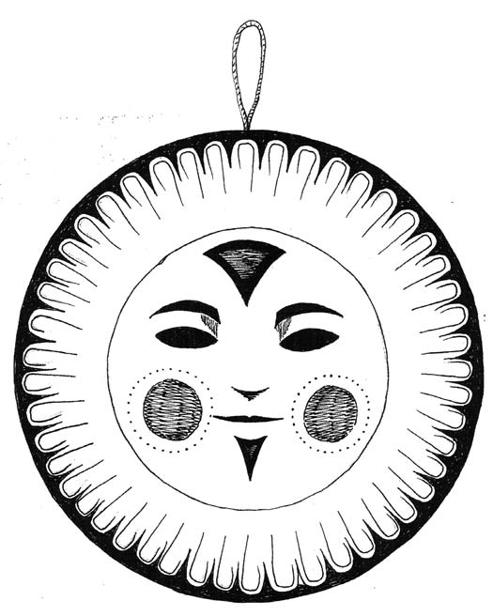

Craft: Elvish Window Ornament

Because we know so little about it, Álfablot is a feast that is open to interpretation. If you’ve already hosted the dead at Halloween, you may choose this occasion to celebrate the

solar aspect of the Light Elves. The following craft is meant to be displayed in the window where it will filter the light of the sun.

Tools and materials:

2 flimsy, plain white paper plates

Plain white paper, the thinner the better

Colored pencils and/or markers

Glue

Scissors

X-Acto or other craft knife

String

Cut out the centers of both your paper plates. Trace one of these cut-out circles on your plain white paper. Draw the

face of the sun or moon inside the circle and color it in. Cut out the face, leaving a quarter inch margin all around. Glue the face into the empty center of one of your plates with the colored side on the convex side of the plate.

Glue a knotted loop of string to the inside edge of one

of the plates. Glue the two plates together, concave side to concave side, then decorate the fluted rim on each side.

In the daytime when the sun is shining in, turn your

ornament so that the colored side faces out. The incoming

sunlight will illuminate the celestial face. When the lights are on inside, turn the colored side in.

At Home with the Elves 47

Elf-Sacrifice

Dead by Christmas Morning

We have not quite finished with the elves, which is just

as well since, with the television off, you’ll need a few

more stories to keep your guests entertained at Álfablót.

We’ve already learned something about the nature of our

friends from the other side of the veil as well as how to

entertain them. In this chapter we’ll examine the more sinister implications of opening your home to the elves.

Queen of the Elves

For years, Hild, middle-aged housekeeper on a sheep farm

tucked somewhere in the green mountains of Iceland, had

graciously volunteered to stay at home and prepare the

feast while the rest of the household attended church on

Christmas Eve. This should have been the first clue that

the housekeeper was not what she seemed, but somehow

it just didn’t click with the widowed farmer who employed

her. You see, in medieval Iceland, no one in his or her right

49

50 Dead by Christmas Morning

mind would offer to stay home alone on the most danger-

ous night of the year.

The “Dead by Christmas Morning” motif is a tradi-

tion that certainly pre-dates both the Old Norse sagas and Christmas itself.10 In the old Icelandic stories, death was not the inevitable outcome for the unfortunate servant left to him or herself on Christmas Eve, but it was a very real possibility. If she was lucky, she might only be driven mad or carried off into the mountains, never to be seen again.

Hild, on the other hand, lives to see the dawn each

Christmas morning and is never any the worse for it. In

fact, she shows every sign of having been busy the whole

night through: the floors are swept, the tapestries hung, and there is the butter,

skyr

, smoked mutton and a box of snowflake breads all ready to be eaten by the hungry churchgo-

ers when they return. Unfortunately, a succession of newly hired shepherds has not fared so well.

If the farm were not so remote, as Icelandic sheep farms

tend to be, the master would take all his hands to church

with him. But the church is a long way off and the house-

hold must set out early in order to make it in time for the Midnight Mass. As for the sheep, they never take a day off; so as long as there are a few patches of grass peeking out from the ice and snow, they must be taken out to graze then returned at nightfall to the comfort of the fold. So, while 10. The tradition lives on in Otfried Preussler’s 1971 children’s novel,

Krabat

, though in

Krabat

it is on New Year’s morning that the journeyman’s corpse is found at the bottom of the stairs.

Krabat

has been translated into English as

The Satanic Mill

which has to be the reason why it has never become a holiday standard in the English-speaking world.

Dead by Christmas Morning 51

the farmhouse remains in Hild’s competent care, one of the shepherds—and it’s always the new guy—must stay behind

to look after the sheep.

And each Christmas morning, the farmer has returned

to find the lone shepherd dead in his bed. Since there is

never so much as a mark on the poor fellow, the farmer

really cannot guess the cause. Hild would seem the obvi-

ous suspect, but surely she was too busy polishing the candlesticks and making pretty patterns in the butter to have murdered anyone? And what motive would she have had

for wishing all of those shepherds dead?

After having buried several young men in his employ,

the farmer decides he will take on no new hands; he’ll stay behind with the sheep himself if he has to. But that summer, a young tough arrives at the farm and applies for a

job. He must be some kind of desperado, for he seems eager to work there despite the rumors he’s heard. The farmer

is reluctant to take him on, but the young man is insistent and, sure enough, he stays to take charge of the sheep on

Christmas Eve.

The tale does not include any awkward encounters

between shepherd and housekeeper over the course of the

day. If the place is anything like the historic Glambaer farm in Skagafjord in the north of the country, then this is not surprising. Icelandic farmhouses are sprawling affairs, and the shepherd’s work would have kept him some distance

from it. Returning at night to the

baðstofa

, or main living quarters, he would have eaten his supper sitting on his bed while Hild was still busy in the kitchen.

52 Dead by Christmas Morning

Wearily, the shepherd wipes his bowl and spoon with a

wisp of straw, stows his dishes and tucks himself into bed.

He fights sleep, but it’s an uphill battle and his eyes are just sliding closed when he hears the housekeeper enter the

baðstofa. Now only feigning sleep, he allows her to fix a bridle about his head. He does not fight her as she tugs at the headstall and leads him out under the cold stars. She climbs on his back and proceeds to ride him at great speed deep

into the mountains.

It would make a less ridiculous picture if Hild had used

the bridle to turn the shepherd into one of those adorably shaggy Icelandic horses, but this is not the case. Her mount is still a man, and her magical instrument is the

gandreiðarbeizli

11 or “elf-ride bridle,” more commonly translated as

“witch’s bridle.” Made from the bones and skin of a recently buried corpse, it allowed the witch to turn any creature or object into a swift, convenient means of transport. It might have been kinder for Hild to have used a milking stool, butter churn or brewing vat to get where she was going, but

then we would have no story.

And before we judge the housekeeper too harshly, it

must be mentioned that detailed instructions for mak-

ing the so-called witch’s bridle date only to the seventeenth century when the Icelanders, like their continental counterparts, had become obsessed with witches of the Satanic

sort and with a malevolent magic grounded in the freshly

turned earth of the graveyard. While the practices of the

early modern era could be downright disgusting, the gan-

11. Yes,

gand

as in “Gandalf.”

Gand

is a word of uncertain meaning but which has retained its undeniably magical overtones.

Dead by Christmas Morning 53

dreiðarbeizli is actual y an artifact of the ancient gandreið, the Elf-Ride or Wild Hunt. While the passing of the gandreið was always an ominous occurrence, its heathen wit-

nesses were usual y more awestruck than horrified. In

Njal’s

Saga

, Chapter 125, the Norse god Odin appears as a black figure on a gray horse inside a ring of flames. The horse is described as a creature of both ice and fire, while the rider uses his torch to ignite the sky above the eastern mountains. Could this be the aurora borealis? The post-saga storytellers of Borgarfjörður tell us that the gandreiðarbeizli made a whistling, rattling sound, as the northern lights are sometimes said to do.

But our housekeeper on her human mount has now

come to a deep and faintly glowing fissure among the rocks.

Without hesitation, she dismounts and clambers down into

it, soon disappearing from sight. What is our shepherd to

do? Though still in human form, the magic has robbed him

of the use of his hands, so he must rub his head against

a boulder to free himself from both the bridle and the

enchantment. There must be more to this young stranger

than meets the eye, for he happens to be carrying a magic

stone in his pocket, and as soon as the bridle is off, he takes the stone in his left palm, immediately blinking out of sight.

Invisible, he follows Hild in among the rocks.

Once through the fissure, we are not in Iceland any-

more. On the other side, the terrain is much smoother. We

are given little description of Elfland, but one would guess that there is no snow here and that the plain is bathed in a golden twilight, for, despite the late hour, the shepherd has no trouble making out the shape of the housekeeper or

54 Dead by Christmas Morning

of the great, gilded hall toward which she is bound. Once

inside its doors, Hild exchanges her housekeeper’s apron

for a queen’s regalia and, gathering her rich skirts in her hands, settles herself in the high seat beside the King of Elfland. There she is attended by her five children as well as a whole host of courtiers. The elves, who appear quite

human, are all dressed to the nines, and the long trestles are laid for a feast. In one corner, however, the shepherd notices an old lady sitting apart from the glittering throng, hands folded, sour-faced and radiating the dark aura of a malevolent fairy.

Queen Hild dandles her children and converses with her

husband. The royal elf family appears at once both happy

and inconsolable. The shepherd observes the bittersweet tableau, at the same time taking care not to tread on any of the dancing courtiers’ toes. Meanwhile, the queen has given one of her gold rings to her youngest child to play with. When the child drops it on the floor, the shepherd swoops down, snatches the ring and slips it on his own invisible finger.

As we know it must, the hour arrives for Queen Hild

to depart. She rises, puts off her queenly robes and knots her kerchief over her hair. Her husband and children are

weeping and tearing at their elfin locks, but what can she do? She is doomed to return to the mortal realm. The elf

king appeals to the grim figure in the corner, but if help is to be had from that quarter, the old lady will not give it. As Queen Hild bids them all a tearful farewell, the shepherd

creeps out of the hall ahead of her, hurrying back across

the plains of Elfland, scrambling up and out of the gap in the rocks just in the nick of time. When Hild climbs up

Dead by Christmas Morning 55

after him, he has pocketed both the gold ring and the invis-ibility stone, replaced the magic bridle about his head and assumed a vacant stare. The erstwhile queen mounts him,