The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs (25 page)

Read The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs Online

Authors: Elaine Sciolino

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #History, #Biography, #Adventure

“Kiss me?” I asked. Was he kidding? He didn’t look crazy or drunk. I almost said, “I’m old enough to be your mother!” Instead, I blurted out, “I’m here with my daughter. Besides,

monsieur,

didn’t you learn you must always greet people first with a

bonjour

?”

“I just wanted to kiss you!” he said, and leaned in to kiss me on both cheeks. I had to laugh. I guess this is what it’s like to be a cougar.

THE FLYING HOUSE OF THE VIRGIN MARY

. . .

The house of the Virgin Mary was transported to Loreto by the “hand of angels,” but not necessarily heavenly ones.

—B

ROCHURE ABOUT

N

OTRE-

D

AME-DE-

L

ORETTE

C

HURCH

I

T IS HEARTBREAKING THAT NOTRE-DAME-DE-LORETTE

Church is so poor and anonymous. It should be rich and famous. It is the church where Claude Monet, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Bizet were baptized; where the funeral mass for Théodore Géricault was celebrated.

The church sits at the bottom of the rue des Martyrs and is dedicated to Our Lady of Loreto. Growing up Catholic in Buffalo, I learned many appellations for the Virgin Mary: Our Lady of Victory, of Lourdes, of Hope, of Perpetual Help, of the Snows, of Guadalupe; the list goes on.

But I had never heard about Our Lady of Loreto. Her story begins in Nazareth, in the house where Mary grew up, the very place

where the Holy Spirit told her she would become the mother of God. Toward the end of the thirteenth century, Turkish invaders threatened to destroy the house, and a band of angels decided to move it to a safer place. They scooped it up and carried it briefly to a site in what is now Croatia and eventually to the Italian hill town of Loreto.

Of course, the real story is less miraculous. In the thirteenth century, the Angeli family, a noble Italian branch of the imperial family of Constantine, thought the Muslim threat was so serious that it was time to move what was believed to have been Mary’s house. So the Angelis (“the angels”) dismantled it stone by stone, sailed with it across the Mediterranean Sea, and reconstructed the house in Loreto.

Ever since, Loreto has been a place of pilgrimage for Catholics. Pope John Paul II called it “the foremost shrine of international prestige devoted to the Virgin.” Pope Benedict XVI made Loreto the last official visit of his pontificate, in 2012. Churches around the world have been dedicated to Our Lady of Loreto. Because her house flew, the lady inevitably became the patron saint of pilots and air travelers.

On the rue des Martyrs, however, Notre-Dame-de-Lorette has been pretty much forgotten. It originated as a chapel in 1646 but was demolished during the Terror that followed the Revolution of 1789. The current church, the first to be built in Paris after the Revolution, dates from 1836; it was designed by Louis-Hippolyte Lebas, who was soon lost to history. Alas, this was not a glorious period for French architecture.

Before I learned how the Virgin’s house created the cult of Our Lady of Loreto, I thought the church might have been named after nineteenth-century female adventurers known as

lorettes

.

Lorettes,

mostly between the ages of fifteen and thirty, were beneficiaries of a general construction boom along the rue

Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. Because new buildings had damp plaster walls that took months to dry, their apartments did not appeal to upwardly mobile tenants. So the owners offered them at low prices to

lorettes,

who were required to regularly wipe the damp walls dry and to hang curtains to give the impression that the neighborhood was well-populated.

Lorettes

earned their living by selling sexual favors on the streets around the church. Unlike many of the neighborhood’s prostitutes, who lived controlled lives in designated houses,

lorettes

had the freedom of working as independent contractors; at first, they were portrayed as fashionable, modern, and entrepreneurial. They preferred “to take the chances of a life of complicated adventures and multiple lovers” than to lead impoverished lives, wrote Théophile Gautier, a contemporary author. Their presence, he said, gave color and unconventional style to the working-class neighborhood.

The

lorettes

were popularized in songs, plays, poetry, stories, and treatises. In his 1843 book

Filles, lorettes et courtisanes,

Alexandre Dumas marveled at the

lorettes,

who, he said, inhabited “with miraculous speed” the new Notre-Dame-de-Lorette neighborhood. He described them as “charming little beings, clean, elegant, coquettish, that one could not sort into one of the known categories. . . . It was a completely new type.”

The painter Eugène Delacroix moved into a vast atelier on my street, rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, and the first object to strike his virtuous eyes was a “magnificent”

lorette

dressed in black satin and velvet. As she got out of a carriage, he wrote in a letter to the writer George Sand, she “let me see her leg up to her belly with the nonchalance of a goddess.”

The embrace of the tight-knit neighborhood community extended even to the

lorettes

. Local merchants gave them food.

Old men paid them to lie next to them in bed, just to warm their bodies. Men of means kept them as part-time mistresses. They were even welcome at the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Church; Paul Gavarni, the neighborhood caricaturist, drew them praying there.

They were also seen as sinister: threats to the social order and the stability of respectable society. They were demonized in literature as acquisitive social climbers who lived well by juggling multiple lovers at the same time. Dumas, for example, was as repelled as he was fascinated by the

lorette

, warning that she was as dangerous as the plague or cholera, “almost an object of terror.”

In his novel

Sentimental Education

, Gustave Flaubert created the most famous—and the most complex—

lorette

in French literature: Rosanette. Flaubert loved whores and frequented them much of his adult life. He portrayed Rosanette as a ruthless opportunist who masterfully played one lover off the other. But he also made her a sympathetic figure who survived a miserable childhood, suffered the death of a child, and eventually achieved social standing by marrying—and burying—a man of wealth. She was a free spirit.

And that’s how I like to think of the

lorettes

: free spirits who were named after a church.

PARIS, WITH ABOUT A HUNDRED CHURCHES

, is not Rome, where the Vatican competes to dominate the landscape and every corner seems to have a church. You wander in and out of them, knowing sooner or later you’ll find a treasure. Paris, by contrast, has a sophisticated, secular air.

The city has its sacred gems: the grand Notre-Dame Cathedral; Sainte-Chapelle, with more than six thousand square feet of stained glass; Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, with its medieval facade. By comparison, Notre-Dame-de-Lorette is a poor cousin that has been allowed to deteriorate over the decades. The French state restores only national monuments, and the city of Paris prefers to invest in parish jewels like Saint-Sulpice.

It took me a while to warm up to Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. Or, rather, it took a while for the church to reveal itself to me. It has two faces. The facade, copied from an ancient Roman temple, has a pediment with sculpted figures representing faith, hope, and charity. In 1905, with secularism gaining force, the French Republic added its own touch above the entrance: a stone with the words

liberté

,

egalité

,

fraternité

.

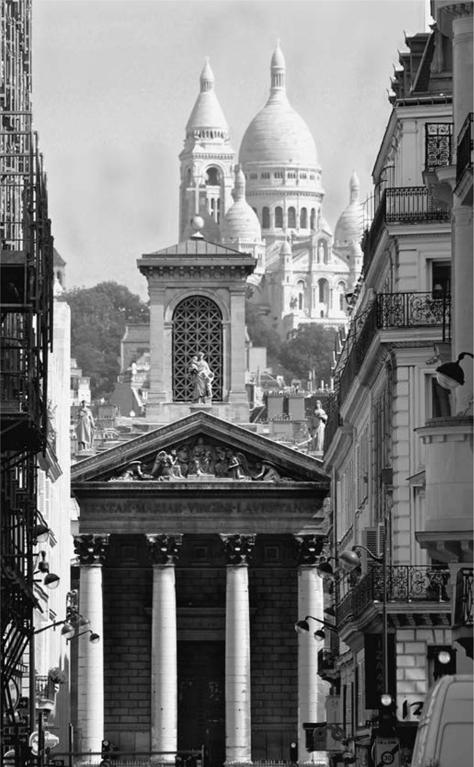

So far, nothing special. But if you look at the church from the base of the nearby rue Laffitte, the view takes your breath away. The domes of the Sacré-Coeur Basilica, up the hill in the distance, hover over the neoclassical facade of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. It is a magical vista of Paris—one captured over and over in photographs and postcards. I once bought a signed, framed watercolor by an unknown artist for five dollars at a yard sale in Washington, D.C. Only after I moved to Paris did I realize that it was this very scene.

The back of the church, which is the side visible from the rue des Martyrs, is dramatically different: a stone hulk without a single redeeming feature, covered with a century’s worth of grime. From this perspective, it looks like a prison with a cross on top, and perhaps the ugliest church in Paris. In 2000, Paris passed a law requiring the facades of buildings to be cleaned every ten years, a practice that has brightened the physical landscape of the

city. But the law does not apply to churches, which makes the blackness of the church stand out even more.

Notre-Dame-de-Lorette can be dismissed as an example of dismal nineteenth-century church building in Paris. “Ugly, heavy, massive, sad, dirty, too,” said Laurence Gillery, the restorer of antique barometers and gold-leaf frames on the other end of the rue des Martyrs. Or it can be celebrated as a miniature of Rome’s Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, with a tall, wide nave, a double aisle, and a deep semicircular apse. There are neither vaults nor arches; there is no cross-shaped transept. “I love this church,” said Bruno Racine, head of France’s National Library and an expert on French art inspired by Italy. “There are wonderful paintings hidden inside; there is marvelous light. It is a little piece of Rome in Paris, a gem.”

That requires a leap of faith—or at least imagination. This is not a place of floral arrangements, heady incense, or a choir of angelic voices accompanied by strings and horns. Decades of dirt—from gas lighting, candle wax, and two fires—cover most of the decorative surface in darkness.

I was sitting in the church one day with my friend Marie-Christine, who had come to pray before the lacquered wooden statue of the Virgin and infant Jesus by the nineteenth-century sculptor Carl Elshoecht. She said that if you pray to this statue, Mary will hear your prayer. Instead of looking up to heaven for divine inspiration, however, I found myself fixated on the scrolls at the top of the ionic columns lining the central aisle. They needed a good scrubbing. What a great summer project for an army of art history majors from an American university, I thought.

Then one Saturday morning I met up with Didier Chagnas, the church’s caretaker and the neighborhood’s self-appointed

historian. He was leading a group of French out-of-towners on a tour of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. He called himself the “keeper of the keys” and proudly carried a huge ring of church keys in his pocket. He told us that the painted decorations beneath the interior grime were considered too modern and extravagant in the mid-nineteenth century. Decades later, that judgment softened—up to a point. An 1881 book by Eugène de La Gournerie on the history of Paris and its monuments notes the church’s exceptional “luxury:” “Gold, marbles, paintings, it is nothing but charm and amazement. . . . Before Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, comfort had not yet entered into holy places. . . . It looks too much like a palace, too much, if we dare, like a ballroom.”