The Origin of Humankind (10 page)

Read The Origin of Humankind Online

Authors: Richard Leakey

Here, in a curve in the stream, we see a small human group, five adult females and a cluster of infants and youths. They are athletic in stature, and strong. They are chattering loudly, some of their exchanges obvious social repartee, some the discussion of today’s plans. Earlier, before sunrise, four adult males of the group had departed on a quest for meat. The females’ role is to gather plant foods, which everyone understands are the economic staple of their lives. The males hunt, the females gather: it’s a system that works spectacularly well for our group and for as long as anyone can remember

.

Three of the females are now ready to leave, naked apart from an animal skin thrown around the shoulders that serves the dual role of baby carrier and, later, food bag. They carry short, sharp sticks, which one of the females had prepared earlier, using sharp stone flakes to whittle stout twigs. These are digging sticks, which allow the females to unearth deeply buried, succulent tubers, foods denied to most other large primates. The females finally set off, walking along single file as they usually do, toward the distant hills of the lake basin, following a path they know will take them to a rich source of nuts and tubers. For ripe fruit, they will have to wait until later in the year, when the rains have done nature’s work

.

Back by the stream, the remaining two females rest quietly on the soft sand under a tall acacia, watching over the antics three youngsters. Too old to be carried in an animal-skin baby carrier, too young either to hunt or to gather, the youngsters do what all human youngsters do: they play games of pretending, games that foreshadow their adult lives. This morning, one of them is an antelope, using branches for antlers, and the other two are hunters stalking their prey. Later, the eldest of the three, a girl, persuades one of the females to show her, again, how to make stone tools. Patiently, the woman brings two lava cobbles together with a swift, sharp blow. A perfect flake flies off. With studied determination, the girl tries to do the same, but without success. The woman takes hold of the girl’s hands and guides them through the required action, in slow motion

.

Making sharp flakes is harder than it looks, and the skill is taught mainly through demonstration, not verbal instruction. The girl tries again, her action subtly different this time. A sharp flake arcs off the cobble, and the girl lets out of yelp of triumph. She snatches up the flake, shows it to the smiling woman, and then runs to display it to her playmates. They pursue their games together, now armed with an implement of adulthood. They find a stick, which the apprentice stone-knapper whittles to a sharp point, and they form a hunting group, in search of catfish to spear

.

By dusk, the stream-side campsite is bustling again, the three woman having returned with their animal skins bulging with babies and food, including some birds’ eggs, three small lizards, and—an unexpected treat—honey. Pleased with their own efforts, the women speculate on what the men will bring. On many days, the hunters return empty-handed. This is the nature of the meat quest. But when chance favors their efforts, the reward can be great, and it is certainly prized

.

Soon, the distant sound of approaching voices tells the women that the men are returning. And, to judge from the timbre of excitement in the men’s conversation, they are returning successful. For much of the day the men have been silently stalking a small herd of antelope, noting that one of the animals seemed slightly lame. Repeatedly, this individual was left behind by the herd and had to make tremendous efforts to rejoin them. The men recognized the chance to bring down a large animal. Hunters who are equipped with the minimum of natural or artificial weaponry, as our group is, need to rely on cunning. The ability to move quietly and to blend into the environment and the knowledge of when to strike are these hunters’ most potent weapons

.

Finally, an opportunity presented itself and, with unspoken agreement, the three men moved into strategic positions. One of them let loose a rock with precision and force, striking a stunning blow; the other two ran to immobilize the prey. A swift stab with a short, pointed stick released a fountain of blood from the animal’s jugular. The animal struggled but was soon dead

.

Tired and covered in the sweat and blood of their efforts, the three men were exultant. A nearby cache of lava cobbles provided raw material for making tools that would be necessary for butchering the beast. A few sharp blows of one cobble against another produced sufficient flakes with which to slice through the animal’s tough hide and begin exposing joints, red flesh against white bone. Swiftly, muscles and tendons yielded to skillful butchering, and the men set off for camp, carrying two haunches of meat and laughing and teasing each other over the events of the day and their different roles in them. They know a gleeful reception will greet them

.

There’s almost a sense of ritual in the consumption of the meat, later that evening. The man who led the hunting group slices off pieces and hands them to the women sitting around him and to the other men. The women give portions to their children, who exchange morsels playfully. The men offer pieces to their mates, who offer pieces in return. The eating of meat is more than sustenance; it is a social bonding activity

.

The exhilaration of the hunting triumph now subsided, the men and women exchange leisurely accounts of their separate days. There’s a realization that they will soon have to leave this congenial camp, because the growing rains in the distant hills will soon swell the stream beyond its banks. For now, they are content

.

Three days later the group leaves the camp for the last time to seek the safety of higher ground. Evidence of their evanescent presence is scattered everywhere. Clusters of flaked lava cobbles, whittled sticks, and worked hide speak of their technological prowess. Broken animal bones, a catfish head, eggshells, and remnants of tubers speak of the breadth of their diet. Gone, however, is the intense sociality that is the camp’s focus. Gone, too, are the ritual of meat eating and the stories of daily events. Soon, the empty, quiet camp is flooded gently, as the stream gently laps over its bank. Fine silt covers the litter of five days in the life of our small group, entrapping a brief story. Eventually all but bone and stone decay, leaving the most meager of evidence from which to reconstruct that story

.

Many will believe that my reconstruction makes

Homo erectus

too human. I do not think so. I create a picture of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and I impute language to these people. Both, I believe, are justifiable, although each must have been a primitive version of what we know in modern humans. In any case, it is very clear from the archeological evidence that these creatures were living lives beyond the reach of other large primates, not least in using technology to gain access to foods such as meat and underground tubers. By this stage in our prehistory, our ancestors were becoming human in a way we would instantly recognize.

THE ORIGIN OF MODERN HUMANS

O

f the four major events in the course of human evolution which I outlined in the preface—the origin of the human family itself, some 7 million years ago; the subsequent “adaptive radiation” of species of bipedal apes; the origin of the enlarged brain (effectively, the beginning of the genus

Homo)

, perhaps 2.5 million years ago; and the origin of modern humans—it is the fourth, the origin of people like us, that is currently the hottest issue in anthropology. Very different hypotheses are vigorously debated, and hardly a month passes without a conference being held or a shower of books and scientific papers being published, each of these putting forward views that are often diametrically opposed. By “people like us” I mean modern

Homo sapiens

—that is, humans with a flair for technology and innovation, a capacity for artistic expression, an introspective consciousness, and a sense of morality.

As we look back into history just a few thousand years, we see the initial emergence of civilization: in social organization of greater and greater complexity, villages give way to chiefdoms, chiefdoms give way to city-states, city-states give way to nation-states. This seemingly inexorable rise in the level of complexity is driven by cultural evolution, not by biological change. Just as people a century ago were like us biologically but occupied a world without electronic technology, so the villagers of 7000 years ago were just like us but lacking in the infrastructure of civilization.

If we look back into history beyond the origin of writing, some 6000 years ago, we can still see evidence of the modern human mind at work. Beginning about 10,000 years ago, nomadic bands of hunter-gatherers throughout the world independently invented various agricultural techniques. This, too, was the consequence of cultural or technological, not biological, evolution. Go back beyond that time of social and economic transformation and you find the paintings, engravings, and carvings of Ice Age Europe and of Africa, which evoke the mental worlds of people like us. Go back beyond this, however—beyond about 35,000 years ago—and these beacons of the modern human mind gutter out. No longer can we see in the arche-ological record cogent evidence of the work of people with mental capacities like our own.

For a long time, anthropologists believed that the sudden appearance of artistic expression and finely crafted technology in the archeological record some 35,000 years ago was a clear signal of the evolution of modern humans. The British anthropologist Kenneth Oakley was among the first to suggest, in 1951, that this efflorescence of modern human behavior was associated with the first appearance of fully modern language. Indeed, it seems inconceivable that a species of human could possess fully modern language and not be fully modern in all other ways, too. For this reason, the evolution of language is widely judged to be the culminating event in the emergence of humanity as we know it to be today.

When did the origin of modern humans occur? And in what manner did it happen: gradually and beginning a long time ago, or rapidly and recently? These questions are at the core of the current debate.

Ironically, of all the periods of human evolution, that of the past several hundred thousand years is by far the most richly endowed with fossil evidence. In addition to an extensive collection of intact crania and postcranial bones, some twenty relatively complete skeletons have been recovered. To someone like me, whose preoccupation is with an earlier period in human prehistory, in which fossil evidence is sparse, these are paleontological riches in the extreme. And yet a consensus on the sequence of evolutionary events still eludes my anthropological colleagues.

Moreover, the very first early human fossils ever discovered were of Neanderthals (everyone’s favorite caricature of cavemen), who play an important role in the debate. Since 1856, when the first Neanderthal bones were uncovered, the fate of these people has been endlessly discussed: Were they our immediate ancestors or an evolutionary dead end that slipped into extinction some thirty millennia before the present? This question was posed almost a century and a half ago, and is still unanswered, at least to everyone’s satisfaction.

Before we delve into some of the finer points of the argument over the origin of modern humans, we should outline the larger issues. The story begins with the evolution of the genus

Homo

, prior to 2 million years ago, and ends with the ultimate appearance of

Homo sapiens

. Two lines of evidence have long existed: one concerning anatomical changes and the other concerning changes in technology and other manifestations of the human brain and hand. Rendered correctly, these two lines of evidence should illustrate the same story of human evolutionary history. They should indicate the same pattern of change through time. These traditional lines of evidence, the stuff of anthropological scholarship for decades, have recently been joined by a third, that of molecular genetics. In principle, genetic evidence has encrypted within it an account of our evolutionary history. Again, the story it tells should accord with what we learn from anatomy and stone tools.

Unfortunately, there is no state of harmony among these three lines of evidence. There are points of connection but no consensus. The difficulty anthropologists face even with such an abundance of evidence is a salutary reminder of how very difficult it often is to reconstruct evolutionary history.

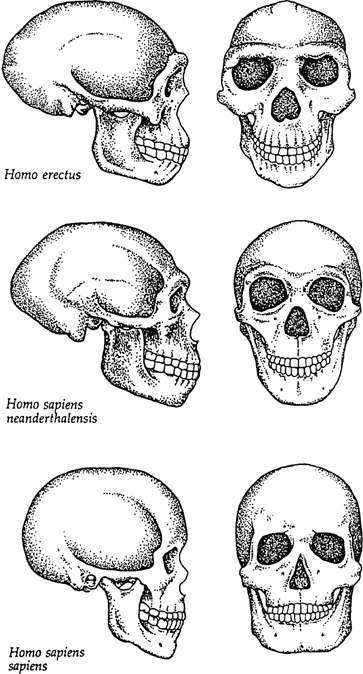

The discovery of the Turkana boy’s skeleton gives us an excellent idea of the anatomy of early man some 1.6 million years ago. We can see that early

Homo erectus

individuals were tall (the Turkana boy stood at close to 6 feet), athletic, and powerfully muscled. Even the strongest modern professional wrestler would have been a poor match for the average

Homo erectus

. Although the brain of early

Homo erectus

was larger than that of its australopithecine forebears, it was still smaller than that of modern humans—some 900 cubic centimeters compared with the average 1350 cubic centimeters of

Homo

today. The cranium of

Homo erectus

is long and low, with little forehead and a thick skull; the jaws protrude somewhat, and above the eyes are prominent ridges. This basic anatomical pattern persisted until about half a million years ago, although there was an expansion of the brain during this time to more than 1100 cubic centimeters. By this time,

Homo erectus

populations had spread out from Africa and were occupying large regions of Asia and Europe. (While no unequivocally identified

Homo erectus

fossils have been found in Europe, evidence of technology associated with the species betrays its presence there.)

More recently than about 34,000 years ago, the fossil human remains we find are all those of fully modern

Homo sapiens

. The body is less rugged and muscular, the face flatter, the cranium higher, and the skull wall thinner. The brow ridges are not prominent, and the brain (for the most part) is larger. We can see, therefore, that the evolutionary activity giving rise to modern humans took place in the interval between half a million years ago and 34,000 years ago. From what we find in Africa and Eurasia in the fossil and archeological record of that interval, we can conclude that evolution was indeed active but in confusing ways.

The Neanderthals lived from about 135,000 to 34,000 years ago, and occupied a region stretching from Western Europe through the Near East and into Asia. They constitute by far the most abundant component of the fossil record for the period we are interested in here. There is no question that ripples of evolution were going on in many different populations throughout the Old World during this period of half a million to 34,000 years ago. Aside from the Neanderthals, there are individual fossils—usually crania or parts of crania, but sometimes other parts of the skeleton—with romantic-sounding names: Petralona Man, from Greece; Arago Man, from southwestern France; Steinheim Man, from Germany; Broken Hill Man, from Zambia; and so on. Despite many differences among these individual specimens, they all have two things in common: they are more advanced than

Homo erectus

—having larger brains, for instance—and more primitive than

Homo sapiens

, being thick-skulled and robustly built (see

figure 5.1

). Because of the varying anatomy of the specimens from this period, anthropologists have taken to labeling these fossils collectively as “archaic

sapiens

.”

The challenge we face, given this potpourri of anatomical form, is to construct an evolutionary pattern that describes the emergence of modern human anatomy and behavior. In recent years, two very different models have been proposed.

The first of them, known as the multiregional-evolution hypothesis, sees the origin of modern humans as a phenomenon encompassing the entire Old World, with

Homo sapiens

emerging wherever populations of

Homo erectus

had become established. In this view, the Neanderthals are part of that three-continent-wide trend, intermediate in anatomy between

Homo erectus

and modern

Homo sapiens

in Europe, the Middle East, and western Asia, and today’s populations in those parts of the Old World had Neanderthals as direct ancestors. Milford Wolpoff, an anthropologist at the University of Michigan, argues that the ubiquitous evolutionary trend toward the biological status of

Homo sapiens

was driven by the new cultural milieu of our ancestors.

Neanderthal relations. Neanderthals share some features with

Homo sapiens

, such as a large brain, and some with

Homo erectus

, such as a long, low skull and prominent brow ridges. They have many unique features, however, the most obvious of which is extreme protrusion of the midfacial region.

Culture represents a novelty in the world of nature, and it could have added an effective, unifying edge to the forces of natural selection. Moreover, Christopher Wills, a biologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, identifies the possibility here of an accelerating pace of evolution. In his 1993 book

The Runaway Brain

, he notes: “The force that seems to have accelerated our brain’s growth is a new kind of stimulant: language, signs, collective memories—all elements of culture. As our cultures evolved in complexities, so did our brains, which then drove our cultures to still greater complexity. Big and clever brains led to more complex cultures, which in turn led to yet bigger and cleverer brains.” If such an autocatalytic, or positive feedback, process did occur, it could help promulgate genetic change through large populations more rapidly.

I have some sympathy with the multiregional evolution view, and once offered the following analogy: If you take a handful of pebbles and fling them into a pool of water, each pebble will generate a series of spreading ripples that sooner or later meet the oncoming ripples set in motion by other pebbles. The pool represents the Old World, with its basic

sapiens

population. Those points on the pool’s surface where the pebbles land are points of transition to

Homo sapiens

, and the ripples are the migrations of

Homo sapiens

. This illustration has been used by several participants in the current debate; however, I now think it might not be correct. One reason for my caution is the existence of some important fossil specimens from a series of caves in Israel.

Excavation at these sites has been going on sporadically for more than six decades, with Neanderthal fossils being found in some caves and modern human fossils in others. Until recently, the picture looked clear and supported the multiregional-evolution hypothesis. All the Neanderthal specimens—which came from the caves of Kebarra, Tabun, and Amud—were relatively old, perhaps some 60,000 years old. All the modern humans—which came from Skhul and Qafzeh—were younger, perhaps 40,000 to 50,000 years old. Given these dates, an evolutionary transformation in this region from the Neanderthal populations to the populations of modern humans looked plausible. Indeed, this sequence of fossils was one of the strongest pillars of support for the multiregional-evolution hypothesis.

In the late 1980s, however, this neat sequence was overturned. Researchers from Britain and France employed new methods of dating, known as electron spin resonance and thermoluminescence, on some of these fossils; both techniques depend on the decay of certain radioisotopes common in many rocks—a process that acts as an atomic clock for minerals in the rocks. The researchers found that the modern human fossils from Skhul and Qafzeh were older than most of the Neanderthal fossils, by as much as 40,000 years. If these results are correct, Neanderthals cannot be ancestors of modern humans, as the multiregional-evolution model demands. What, then, is the alternative?