The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (14 page)

Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

The first time Swain and his team rolled out of Forward Operating Base Naray, they made it only a dozen miles up the road, to the village of Barikot, before half of the trucks broke down. They went back to Naray to regroup and try again. This time they used just the ATVs—Polaris Sportsman MV7s, painted Army green. As the sun set, Swain and around a dozen troops put on their night-vision goggles and began motoring north, then west. Snyder and his Special Forces team, who were on a separate mission, also joined them, likewise driving ATVs. Two platoons of Afghan National Army (ANA) troops—some thirty Afghans in total—and about six U.S. mortarmen followed in Ford pickup trucks.

They stopped briefly at Barikot, which was on their way, s, swh o Swain could ask the deputy head of the Afghan Border Police, Shamsur Rahman, to come along. Rahman and Swain had developed a strong relationship during a previous operation and had participated together in shuras with the Kotya elders. Rahman was well connected and hailed from Lower Kamdesh Village. He would be an asset on a trip like this.

Rahman wasn’t at the station in Barikot—he was on leave—but his boss, Afghan Border Police Commander Ahmed Shah, was there, and Swain considered him a friend as well. Shah cautioned Swain not to go up to Kamdesh Village. “It’s a bad place,” he said. The road was dangerous; insurgents had tried to blow up his jeep on a recent tour. Swain thanked his friend for the warning, and the team took off again. It was dark by now, so the enemy, presumed not to have night-vision goggles, would be at a disadvantage.

They stopped near the hamlet of Kamu to drop off one of the ANA platoons, under orders to keep watch on a known IED-maker who had a home there. That section of the road was a prime place to hide an IED, and Swain wanted to take precautions to make sure his expedition wouldn’t get hit on its way back.

By 2:00 a.m. local time, Swain, Snyder, and their teams had arrived at the hamlet of Urmul, northwest of and down the mountain from Kamdesh Village. They set up security and tried to grab some sleep. After an hour or two, Snyder shook Swain awake. Snyder thought the plan was for both of their teams to hike up the mountain together to Kamdesh Village, and he wanted to get going before it got too hot. A groggy Swain didn’t quite understand what Snyder was talking about; he informed him that while his mortarmen would turn the tubes in that direction and offer fire support if needed, Cherokee Company was going to stay at the bottom of the mountain. The 3-71 Cav troops were there, after all, to find a new location close to the road for a U.S. base and a provincial reconstruction team, not to take a four-hour mountain hike. Snyder said that he and his men were going to head out. Swain told his fire-support officer, Sergeant Dennis Cline, where to aim his mortars if the Special Forces troops needed them. He checked the perimeter and then tried to go back to sleep, worrying that the Special Forces troops would mess up his mission to make nice with the locals, as had been known to happen before.

Although referred to as a single village, Kamdesh actually comprised four distinct communities: Upper Kamdesh, Lower Kamdesh, Papristan, and Babarkrom. (Two other, outlying villages, Binorm and Jamjorm, were separate from Kamdesh and had non-Kom Nuristani populations.) On the map, Kamdesh was only a mile distant from Urmul, but the topographic reality meant that the two-thousand-foot climb would take about three hours—for Americans, at least; even geriatric Kamdeshis could make their way up the mountains like spry goats. Of course, it helped that they weren’t carrying eighty pounds of gear apiece.

At dawn, Swain awoke, checked his perimeter again, then opened and ate an MRE—short for “meal ready to eat,” the basic ration for troops in the field—and headed for the Afghan National Police station down the road. Outside the station sat the hollow shell of a Soviet armored personnel carrier, once used to transport heavy guns, cargo, or half-platoons of Soviet fighters. Nuristani folklore included many tales about how the locals had stood up to the Soviets in the 1980s. They’d attacked the invaders with clubs, stolen their guns, and later ambushed their armored vehicles—or so the stories went. At least five abandoned such vehicles were scattered around the immediate area like trophies, or monuments to an empire’s hubris.

One of the many carcasses of Soviet vehicles, this one right outside the outpost.

(Photo courtesy of Matt Meyer)

At Swain’s request, an Afghan policeman ran up the mountain to Kamdesh to fetch the district administrator to meet with the Americans. Swain wanted to explain the Army’s plan to bring in a provincial reconstruction team—or, in the case of underdeveloped Nuristan, essentially a provincial

con

struction team—to help develop the region. Swain intended to ask the man for his help.

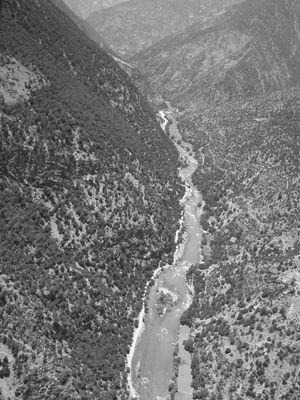

He looked around while he waited. This was a gorgeous part of the world. He gazed up at the steep green mountains and then down into the blue Landay-Sin River. He could see right through the water, all the way to the bottom. Part of him wished he had his kayak and fishing pole.

The Landay-Sin River and its valley.

(Photo by Ross Berkoff)

Hours later, the policeman returned with the administrator for Kamdesh District, Gul Mohammed Khan—by reputation effective, well connected, and, to some, suspect for his ties to HIG. He, Swain, and a small group of American soldiers and Nuristanis sat in an orchard where small oranges hung from trees. Looking tired and seeming stoned, Mohammed recounted to Swain some of the history of Kamdesh. When asked about insurgents in the area, he insisted that the valley was relatively peaceful, save for the feud between the Kom people and the Kushtozis over water rights and other grievances.

Swain explained what the U.S. military wanted to do in the region. This didn’t get much of a reaction from Mohammed. When Swain added that the soldiers would set up camp nearby as the PRT was being built, the district administrator seemed ambivalent.

While preparing to hand over his area of operations to Colonel Nicholson three months before, Colonel Pat Donahue had made it clear that he didn’t think it made much sense to send troops into Nuristan. First, the United States simply didn’t have enough soldiers in the country to establish a strong presence there: Regional Command East was a sprawling, mountainous territory roughly the size of North Carolina, and the U.S. force numbered only about five thousand troops.

Second, Nuristan Province was incredibly isolated, and its terrain forbidding, with jagged mountains rising as high as eighteen thousand feet. Operations there were grueling; there weren’t many functional roads. Third, there wasn’t much of a threat involved. Nuristanis were insular, Donahue believed; they didn’t like anybody. The men with guns there seemed more like local militias protecting their homes than anything else.

His replacement, Mick Nicholson, saw Nuristan quite differently.

In the Pech Valley in Kunar Province, south of Nuristan, Nicholson had witnessed the hits inflicted on 1-32 Infantry by an enemy well armed with IEDs and rockets, which the Army was convinced were coming from Pakistan. Nicholson, Fenty, Byers, Berkoff, and others had talked about the influx of these armaments from across the border. Kamdesh was close to the road where three of the valley systems from the north merged on their way from Pakistan; if 3-71 Cav could secure a location near this road, the men decided, it might be able to disrupt the threat to 1-32 Infantry in Kunar Province—and to Americans and Afghans in Kabul. Given that American policy forbade troops from entering Pakistan, where so many enemy forces were safely ensconced, Nicholson also figured that if the brigade could set up outposts in adjacent Nuristan, the United States might have more success in killing insurgents, possibly even members of Al Qaeda.

The task in Kamdesh District now fell to Nicholson’s new commander of 3-71 Cav, Mike Howard. The brigade didn’t have enough troops to heavily garrison the entire region, so deployment would have to be strategic and selective. Since his arrival at Forward Operating Base Naray, Howard had spent quite a bit of time talking with Nuristan’s governor, Tamim Nuristani. Nuristani’s grandfather had been a famous general who fought the British in the Third Anglo-Afghan War, in 1919, and his father had been mayor of Kabul until the Communists took over—at which point Nuristani himself, then in his early twenties, had gone to the United States. He’d driven a cab in New York City, opened a fried chicken joint in Brooklyn, and later owned a chain of pizzerias in Sacramento called Cheeser’s. After the Taliban fell, he’d returned to Afghanistan and worked his way into Karzai’s good graces until eventually Karzai appointed him governor.

For months, Nuristani had been pushing for the United States to put a PRT in the provincial center of Parun, but American military commanders had visited the area and deemed it too isolated, as it was accessible basically only by air or on foot. Nuristani’s second choice was Kamdesh Village. He told Howard that if he could get the Kom people residing in Kamdesh District on the side of the Afghan government, the rest of eastern Nuristan would follow. Nuristani himself was Kata, so he didn’t personally have much sway over the elders of Kamdesh—in fact, quite the opposite. But that was all the more reason to locate the PRT near the largest and most influential Kom community, to improve the chances of the combined United States and Afghan government forces’ being able to win over a population naturally skeptical of its governor. Additionally, from the Americans’ perspective, putting a base by the road to Kamdesh not only would stop the insurgents from using that road but also would protect the only means of resupplying the camp itself.

Here in particular, proximity to a road was a crucial feature of the PRT’s potential location, because air assets were relatively scarce in Afghanistan. The Pentagon and the Bush White House were focused on Iraq, so that was where the helicopters were. It irked Nicholson. In his area of operations, he was responsible for eleven different provinces, seven million Afghans, and almost three hundred miles of border with Pakistan—and for all of that, he had only one brigade of troops and one aviation brigade. That was it. By contrast, there were fifteen troop brigades in Iraq, and four aviation brigades. It didn’t make sense to him.

“Iraq is smaller and has fewer people than Afghanistan,” a frustrated Nicholson would say, trying to explain how nonsensical was the relative dearth of resources in Afghanistan. “And by the way, this is where the war started.”

Swain still didn’t know where near Kamdesh Village he should put the PRT. He and his troops hopped on their ATVs and drove around a bit, looking for some suitable land, but every possible location either was already being used or was inhospitable to construction.

They went up the road to the west, to Urmul. As they were walking up the mountain from there, on the way to Kamdesh Village, they came upon a school. It looked legitimate. Photographs of Afghan President Hamid Karzai were hung on the wall, a good sign that the locals were supportive of the new government in Kabul. The Americans walked back down the hill and down the road and saw a medical clinic. The sign said it housed an antituberculosis program sponsored by Norwegian Church Aid and the Norwegian Refugee Council. This must be where the bad guys came to get cleaned up before they headed to Pakistan, Swain mused.

The scouting party returned to the Afghan National Police station. Swain looked around the small surrounding compound. This right here might work, he thought. It was by the road, and there was a potential helicopter landing zone right outside the gate, next to the river. Obviously, the site—at the bottom of three steep mountains—wasn’t the best place in the world for a base; security would be a concern. But Swain knew that Howard had plans to send at least an entire company—plus mortarmen and snipers—to defend the PRT. It could be properly protected, Swain reasoned, and if they had to put the PRT next to the road, it was going to be at the bottom of the mountains in any case. Moreover, in this location they could be next to the police station, partnering with the government, and Urmul—where the district administrative offices were headquartered—was just down the road to the southwest. Kamdesh Village was right up the mountain to the south. Nothing that the United States did in Afghanistan could be deemed perfect, but this might be good enough, at least for now.