The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (43 page)

Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

“Shut up,” he told Del Sarto. “I know that’s an Apache.” Medevacs were Black Hawks.

Soon a Black Hawk did arrive. The landing zone was so small that the pilots would have had every right to refuse to land, but they brought the bird down anyway. Faulkenberry and Sultan, the most seriously wounded of the men, were the last to be loaded on so that they would be the first off when they got to Forward Operating Base Naray. Pfeifer and another private put them in, banged the shell of the Black Hawk to give the all-clear, and watched as it flew them out of Nuristan forever.

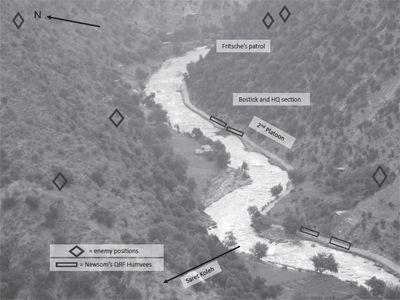

Roller’s view of the eastern side of Saret Koleh.

(Photo courtesy of Dave Roller)

The battle was nearly over, but a new commander was finally on his way. Joey Hutto landed at Combat Outpost Kamu and updated Kolenda over the radio: most of the men were now rolling out of the valley, he reported, but Fritsche’s body was still on the mountain; they’d have to send a team to go back and get it. Kolenda and Hutto decided that Roller and 1st Platoon should stay where they were, in a good position to call in bombs and cover whatever force went into the valley to recover the corpse. It was not uncommon for this enemy to ransack or even mutilate any bodies left on the battlefield, and the Americans couldn’t let that happen to Ryan Fritsche.

Hutto headed to Camp Kamu’s operations center, picked up a radio, and prepared formally to assume command.

He froze for a minute.

It was not pleasant, what he had to do: he needed to announce that he was replacing Tom Bostick, his close friend, because he’d been killed. Even though Hutto, as the new commander of Bulldog Troop, had inherited his predecessor’s call sign, “Bulldog-6,” he decided not to identify himself by that right now; he knew that many of Bostick’s troops would be listening, and he was concerned that some of them might not have heard the news yet. It just felt wrong to him—as if by his use of the call sign, he would be not only usurping Bostick’s place but also alerting the men to the loss of their leader in the crassest way possible.

Instead he said simply, “Captain Hutto is now on the ground.” Kolenda, in his first subsequent transmission, welcomed his new troop commander and called him Joey. It wasn’t protocol, but the lieutenant colonel was nothing if not empathetic. He then gave Hutto orders as “Bulldog-6,” and that became Hutto’s name from then on. And this was how many in the field, among them Nate Springer, learned that their friend and commander Tom Bostick had been killed.

In Martinsville, Indiana, Deputy Sheriff Volitta Fritsche, Ryan’s mother, looked out her window and saw several sheriffs’ cars in her driveway. She had taken some time off from her job due to her husband’s illness and death, but she was scheduled to return to work just two days later, so she couldn’t imagine why all her coworkers had shown up at her house.

Then she saw a man she didn’t recognize get out of one of the patrol cars. He was dressed in an Army uniform. After he exited the car, he put on a beret. Her heart started pounding.

“This can’t be happening,” she said aloud.

One of her coworkers knocked on the door. Volitta Fritsche answered it but pointed at the soldier and said, “He can’t come in here!”—hoping that somehow, by denying him entry, she might be able to prevent the inevitable.

The soldier, and another, entered anyway. The one she’d seen through the window informed her that her son had been reported missing in action. The news was devastating, but it also gave her a glimmer of hope.

“What does that mean?” she asked. “Does that mean he’s still alive?”

“The only information I have, ma’am, is what I told you,” said the soldier.

“He could be alive?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“Was he taken prisoner?”

“I don’t know, ma’am.”

“These people have been beheading prisoners,” she said. “Could he have crawled off and be hiding in a cave?”

“Yes, ma’am,” the soldier said. “Anything’s possible at this point.”

After her visitors left, Volitta called her daughter-in-law, Brandi, who had been told the news by a different set of soldiers.

“Where could he be?” asked Brandi, crying.

“He’s probably hiding somewhere in the mountains,” Volitta suggested. “He’s good at that kind of thing. Remember, land navigation is his forte.”

“I know,” Brandi said. “I’m just so scared.”

A few hours later, the soldiers returned to Volitta Fritsche’s home to tell her that they had some new information: Ryan was still MIA, but now they also knew that he had been wounded in action.

“Is he okay?” Volitta asked.

“I don’t know, ma’am,” the soldier replied. “They’re reporting he was shot in the head.”

“I don’t understand,” she said. “If they saw him take a hit, and they’re back to safety, why don’t they know Ryan’s condition?”

“They can’t find him, ma’am.”

“ ‘Can’t find him’? What do you mean, they can’t find him? You mean they left him out there?”

“They said the fighting was so intense, they couldn’t get him out,” the soldier said. “I’m sorry.”

“I thought you guys didn’t leave anyone behind!” Volitta cried. “

Ryan wouldn’t have left one of his guys behind!”

The Landay-Sin Valley near Saret Koleh was now teeming with U.S. aircraft, bombing every location that the remaining men on the ground—Roller, primarily—called in. Hutto ordered that bombs be dropped in a circle around the spot where Fritsche had last been seen. Newsom wanted to head back into the valley, but he’d been told by Roller that the higher-ups wanted him to hold off for now; they were devising a plan.

Hutto weighted himself down with guilt over Fritsche’s death. He was the one who’d sent the staff sergeant to 2nd Platoon; he’d even escorted him to the helicopter that would fly him to Combat Outpost Kamu. On that first night of his new command, Hutto got word to Newsom that he should send a quick reaction force to recover Fritsche’s body. A reluctant Morrow went along on the mission, remaining in the Humvee and staying in radio contact with the members of the QRF as they hunted for the corpse.

The searchers couldn’t see much by moonlight, and the bombardment had pulverized most of the rocks into loose gravel, which made climbing even more difficult. When they turned on their white lights, they saw further evidence of bombing and strafing runs from earlier in the day. They found several former fighting positions littered with empty water bottles and, in one case, a soft SAW ammo carrier. Morrow guided them over the radio to the location where Fritsche had been killed.

His body wasn’t there.

Pfeifer, Newsom’s driver that day, sat with the lieutenant in a second Humvee; he was so drained that he kept nodding off behind the wheel. Newsom nudged him every minute or so to wake him up. Each time, Pfeifer would open his eyes and smile: Good to go. The kid was just like that, Newsom thought.

The QRF troops walked down the mountain. Back in their Humvees, they stopped off at the former casualty collection point to pick up some assault packs that were supposed to be there but weren’t. The evening, it seemed, had a theme.

The searchers did find some human remains—skull fragments, almost certainly from Bostick—which they collected in an ammunition can that Morrow held in his lap during the drive back to Combat Outpost Kamu. Otherwise, the QRF returned from the mission emptyhanded.

As the sun rose on the Landay-Sin Valley, Roller radioed to Hutto that 1st Platoon needed to head back to Combat Outpost Kamu. He and his men were spent, down to thirty seconds’ worth of ammunition for the 240 machine gun and almost out of water. Hutto gave them permission, but this, too, added to his guilt over Fritsche: after sending him to the battlefield in the first place, he was now approving Roller’s request to leave his body behind there, all alone. And while Hutto believed those who said the kid had been KIA, he hadn’t seen it for himself.

In fact, the hunt for Fritsche’s body had not been abandoned: Kolenda’s boss, Colonel Chip Preysler, committed a different unit from his brigade, the 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, to conduct another search the next night. Also known as the ROCK Battalion, the unit was led by a contemporary of Kolenda’s, Lieutenant Colonel William Ostlund, who gave the impression that he thought his men were tougher than those who’d already tried to find Fritsche—maybe tougher than anyone, period. Ostlund landed his tactical command post on Hill 1696, overlooking the staff sergeant’s last known location; the ROCK’s Chosen Company landed at Combat Outpost Kamu, where its members were briefed by Hutto and others from 1-91 Cav. Then the seventy or so troops from Chosen Company walked to Saret Koleh. Wilson, eaten up by guilt, joined them. As he hiked the mountain with the Chosen Company troops, the sergeant worried that they wouldn’t be able to find Ryan Fritsche—that perhaps he’d never be found at all. He wondered what the insurgents had done to poor Fritsche’s corpse. The worst thoughts possible ran through his mind.

But the Chosen Company troops

did

find Fritsche, lying faceup in the very spot where he’d been killed; either he’d been taken away and then returned there by the enemy or the first search party had somehow missed seeing him. He had been stripped of his personal effects and military equipment: his body armor, weapon, and boots were gone. He was wearing just a shirt, pants, and socks. His arms were folded across his chest. His eyelids were closed. An entry wound blemished his left temple, and a matching exit wound showed behind his right ear.

Fritsche was put on a Skedko plastic stretcher and carried down the hill. He was taken to Combat Outpost Kamu, where his remains were officially identified. Three days after Ryan Fritsche was killed, the soldier in his green uniform and Army beret pulled up to Volitta Fritsche’s Indiana home for one final visit, this time to tell her that all hope was lost, and her beloved son—the Little Leaguer and high school basketball center with gifts of determination and beauty—was gone.

Dave Roller was distraught at the loss of Bostick; everyone in Bulldog Troop was. But for Roller, the hardest thing of all was his belief that even as he and his fellow soldiers were out there fighting for their lives, no one back home cared. Ninety percent of the American people would rather hear about what Paris Hilton did on a Saturday night than be bothered by reports on that silly war in Afghanistan, Roller thought. Of this he was convinced. That the people they’d been fighting for would never even know their names made the death of soldiers such as Tom Bostick and Ryan Fritsche all the more tragic.

CHAPTER 18

T

he U.S. Army had been moving Joey Hutto around since he was a boy. In the eighth grade, he had relocated from Enterprise, Alabama, when his mom, a single mother, married an Army sergeant who was being moved from Fort Rucker to a base in Missouri. Eventually the sergeant and Hutto’s mom split up, and his stepfather faded out of his life, but the Army didn’t. He signed up right out of high school, and his fitness and determination were so apparent to one recruiter that Special Forces brought him on board the following year. He spent the next decade running in and out of Central and South America, mostly training host nations’ armies in Special Forces tactics—how to clear a building during a hostage situation, how to implement what was then the prevailing theory of counterinsurgency, how to provide security for VIPs, how to combat narcoterrorists. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant at Fort Benning Officer Candidate School in 2002 and ended up in Germany, where he and Bostick became fast friends. At Forward Operating Base Naray, he’d served as the assistant operations officer for 1-91 Cav’s Headquarters Troop.

When Hutto touched down at the landing zone at Combat Outpost Keating, he was met by an officer who had just been in Bostick’s hooch at the operations center, trying to separate the fallen troop leader’s military gear from his civilian items. Hutto thanked him and took over. He entered Bostick’s small room and closed the curtain.

Beyond that split-second embrace with Kennedy back at Forward Operating Base Naray, Hutto hadn’t had a moment to focus on his dear friend: he’d been too involved in coordinating the response to the enemy presence, working to expedite the exit of Bulldog Troop from the battle, and then trying to recover Ryan Fritsche’s body. He hadn’t even had a chance to talk to his wife yet, because immediately after Bostick’s death, the unit had been “blacked out”—meaning that no one could call or write home—for fear that Jennifer Bostick might hear the news through the grapevine and not via official Army channels. This moment behind the curtain of Tom Bostick’s hooch was the first time in days that Hutto didn’t have soldiers swarming around him, radios going off.