The Oxford History of the Biblical World (65 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

MARY JOAN WINN LEITH

I

n the Persian period the concept of “Israel” changed. Before the Babylonian exile, Israel was defined not by worship but by its independent geopolitical existence, by occupying its own land. Exile and Diaspora forced a new, evolving sense of identity. The Persian period (539–332

BCE

) constitutes an era of both restoration and innovation. The religious attitudes and practices characteristic of postexilic Judaism did not originate in the Persian period. The centrality of the Jerusalem Temple and of public worship at its sacrificial altar are only the most obvious in a list of continuities from preexilic Israel; others include the priestly families, the practice of circumcision, Sabbath and Passover observance, and prohibitions against mixed marriage. At the same time, however, with the figures of Ezra and Nehemiah we reach the end of biblical Israel.

In leading Jewish circles during this period, written words perceived as having originated in Israel’s distant past came to assume a primacy previously uncontemplated—if not unanticipated (see 2 Kings 22–23)—in legitimating the practice of worship and for determining social and ethnic identity. The movement toward compiling a biblical canon accelerated. The Psalms, the editions of the prophetic books, and, most important, the Torah or Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) approached their final shape during the Persian period. The period is also rich in literature by Yahwistic prophets, poets, priests, and philosophers whose names often elude us; they wrote pseudonymously, claiming the names of ancient Israelite heroes or sages, covering their creations with a validating veneer of antiquity. Late biblical works frequently quote from older Israelite writings (now become scripture) and contain early examples of traditional Jewish biblical exegesis. One of the era’s most arresting images is that of Ezra the scribe, a contemporary of Socrates, reading aloud

the “book of the law of Moses” (Neh. 8.1) to women and men assembled at the gates of rebuilt Jerusalem. Ezra’s reading, however, is supplemented by interpreters (Neh. 8.7–8)—or possibly translators—whose task is to ensure that all the listeners correctly understand the meaning of the Torah.

Formerly a nation with fixed borders, postexilic Israel became a multicentric people identified not geographically or politically but by ethnicity—an amorphous cluster of religious, social, historical, and cultural markers perceived differently depending on whether the eye of the beholder looks from inside or from without. The identity of this Israel could not be threatened by the Persian hegemony over the homeland or by military aggression. Rather, the danger to this new Israel lay in a different sort of boundary transgression: ethnic pollution, an offense variously defined.

The pronounced Jewish sectarianism of the Hellenistic and Roman periods, embodied in such groups as the Samaritans, the Qumran community, the Pharisees, and the earliest Christians, has its roots in the Persian period. Typically for this period, while Ezra and Nehemiah attempted to restrict membership in the privileged group they considered to be “Israel” (Ezra 10.2, 7, 10), the Bible itself preserves traces of rival Jewish groups engaged in an ideological struggle against the vision of Ezra and Nehemiah. During the Persian period Jewish communities—Yahweh worshipers—flourished not only in Judea, but also in Babylonia, Persia, and Egypt, in neighboring Samaria to the north, and in Ammon to the east.

The term

Jew

originates as an ethnic label for a person whose ancestry lay in the land of Judah (see 2 Kings 16.6); the earliest occurrence of the term to designate a religious community is in Esther 2.5, a Hellenistic novel set in the Persian court. The word is used in a broad sense in this chapter to designate Yahweh worshipers—be they exclusive or syncretistic—in the Persian period.

To what extent were Jews, whether in the Diaspora or the Levantine homeland, influenced by Persian or Greek culture? The Persian period encompasses, after all, the Greek Classical Age. (Conventionally spanning the years 479–323

BCE

, this age is the time of Periclean Athens: the Parthenon, Phidias and Praxiteles; Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides; Socrates and Plato and Aristotle, the tutor of Alexander before he became “the Great”; the historians Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon.) In the eastern Mediterranean world, including the western territories of the Persian empire, the era sees the increasing presence of Greek artists, writers, doctors, adventurers, and especially mercenary soldiers, frequently in the pay of non-Greeks (including Persians).

What did cultural assimilation entail, specifically in the case of the Jewish encounter with Hellenism? The assumption that a Jew’s adoption of Greek culture meant a renunciation of Judaism is refuted by the example of Philo, the great Jewish philosopher of the first century

CE

. Judaism in the later Second Temple period became deeply hellenized without any loss of communal historical consciousness or national culture.

How deeply Greek culture might have penetrated Judah and Samaria—or the Diaspora, for that matter—in the Persian period is difficult to determine. Students

of fourth-century

BCE

cultural history have increasingly recognized a pre-Alexandrine Hellenic

oikumene

of sorts in the western Persian empire. During this period the Phoenicians were the primary conduit of Hellenism to the Levant, although less in terms of political and religious thought than of material culture and artistic taste. Evidence of extensive trade with Greece and the west in the form of imported high-prestige-value eastern Greek and Attic pottery appears in the Phoenician cities of the coast and in the Shephelah, but far less of such pottery is found at poor inland sites in Judah and Samaria. Eastern influences (Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian) still dominated the material culture of inland Palestine.

Any exposure to Greek culture in Judah and Samaria must have been indirect. There are no references, biblical or otherwise, to Greek natives in Judah or Samaria before the arrival of Alexander, although Greek mercenaries might have served in Persian garrisons in Palestine, including Nehemiah’s fortress in Jerusalem. The coinage of Judah and Samaria in the fourth century includes devices in imitation of Greek coins. But the adoption of Greek images such as the Attic owl or the head of the goddess Athena need not be interpreted religiously. Provincial mints copied foreign issues, particularly the ubiquitous and trustworthy Athenian tetradrachm.

In small ways, such as their predilection for seals with Greek subjects (probably from Phoenician workshops), Samarians (if not the Judeans) seem to have been attracted to Greek culture, even if they had no firsthand experience of it. Nevertheless, there can be no cultural receptivity unless the receiving culture has receptors attuned to new influences. Without a degree of hellenizing groundwork already having been accomplished by cultural interactions, the world conquered by Alexander, including Syria-Palestine, would have been far more resistant to the Greek ways that took root with such ease.

The paucity of Persian artifacts in the archaeological record of western lands subject to the great king led earlier scholars to deny significant Persian artistic, religious, or cultural influence. They assumed that the Persians were interested only in maintaining the flow of tribute into the national treasuries but otherwise allowed their subjects to go their separate religious and economic ways. More recently scholars have interpreted the Persian art that has been found in the western satrapies as evidence of a conscious imperial propaganda program. We now consider the Persian impact on the western reaches of the empire to have been subtle but assertive, with more cultural interaction than had been previously supposed.

Beginning with Darius I (522–486

BCE

), Zoroastrianism was the national religion of the Achaemenids, the official name for the Persian royal family. This religious tradition included purity laws (to prevent pollution by corpses and bodily emissions) and the belief in a cosmic struggle between Justice, upheld by the great god Ahura-mazda (“Lord of Wisdom”), and the “Lie.” The struggle would climax in a final, apocalyptic battle. Zoroastrian priests, called magi, officiated at all sacrifices, usually on mountaintops. There is no evidence for any imperial proselytizing, nor was the adoption of Zoroastrianism a necessary condition of advancement for a nonnative official in Persian service. There is little if any effect of Zoroastrian elements on Judaism in the Persian period. Most discussions of Persian influence on Judaism now look to the Hellenistic and Roman periods as the era of significant cross-fertilization.

One effect of Persian domination was the spread of the Aramaic language throughout

the empire. Originally the native tongue of small Syrian and Mesopotamian states, Aramaic became the international commercial, administrative, and diplomatic language of the Assyrian empire in the eighth century. Aramaic’s alphabetic script was more flexible than Akkadian cuneiform. Second Kings 18.26 (= Isa. 36.11) shows Aramaic in diplomatic use, as well as the general Palestinian populace’s ignorance of it in the eighth century. During the Neo-Babylonian period, however, Aramaic became the main spoken language of the Neo-Babylonian empire, and subsequently the Indo-European Persians adopted this Semitic cousin of the Hebrew language for all aspects of their written communications and records. Eloquent testimony to this fact appears in the book of Ezra, which employs Aramaic for official Persian documents (Ezra 4.8–6.18; 7.12–26) and some narrative.

After the exile the use of Aramaic was on the increase in Palestine. Preservation of Israel’s ancestral language was a particular concern of Nehemiah, who complained that the children of mixed marriages did not know Hebrew (Hebrew

yehudit,

literally “Judahite”; Neh. 13.24; see Isa. 36.11). Hebrew did not die out, but it was gradually replaced by Aramaic as the language most commonly spoken. The biblical texts attributed to the Persian period were written in Hebrew, attesting to its continued use as a literary language, but late biblical Hebrew—in Chronicles, for example—contains numerous Aramaisms. Hebrew and Aramaic inscriptions on coins and seals of the Persian period from Judah and Samaria alike show both languages being employed in official governmental contexts. Hebrew names also occur in Aramaic texts.

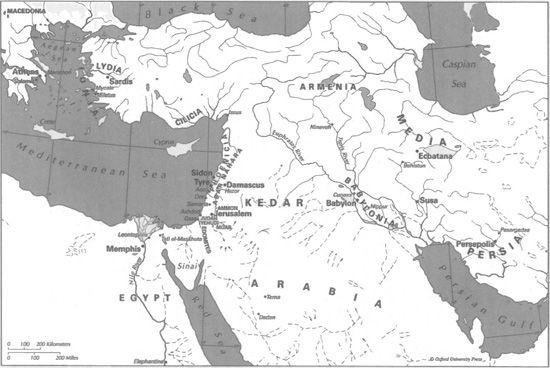

The two centuries of the Persian period (the early Second Temple period) in Syria-Palestine are framed by two dates. Achaemenid Persian control began in 539 with the conquest of Babylon by the army of King Cyrus II (“the Great,” 559–530). It ended in 332, when Alexander the Great (336–323), having defeated the Persian king Darius III Codomanus (336–330) in the battle of Issus (in Cilicia near the Syrian border), marched into and took possession of the Levant. In 539 Cyrus’s capture of Babylon meant that the territories of the Babylonian empire, including Syria-Palestine, now belonged to the Persian empire. Two centuries later, by his victory at Issus, Alexander annexed the western Persian empire including Syria-Palestine, formerly the fifth Persian satrapy of Abar Nahara (“Across the [Euphrates] River”). Archaeologists divide the era into two phases, Persian I (539/8-ca. 450) and Persian II (ca. 450–332). These chronological anchors, however, belie the often frustrated attempts by modern historians to make sense of the erratic textual and archaeological evidence, not only for chronology but even more crucially for Jewish religious and social history in the shadowy intervening years.

The starting point for our discussion of the Persian period as it relates to biblical history is actually 586

BCE

, when the Babylonians looted and destroyed the Jerusalem Temple, razed much of the city along with its walls, and exiled an indeterminate number of Judah’s ruling elite to Babylonia (2 Kings 25.8–21). The exiles of 586 joined other Judahites, among them King Jehoiachin and the priest-prophet Ezekiel, who had previously surrendered to Nebuchadrezzar II in 597 (2 Kings 24.12–17; Jer. 52.28–30). A second significant group of Jews were exiles by choice in Egypt, where they had dragged the reluctant prophet Jeremiah (Jer. 43). Their fate is unclear, but the exilic revision of the Deuteronomic History could have occurred in this community, out of which grew the large Jewish population of Hellenistic Egypt.

The Near East during the Persian Empire

Clearly, intense theological ferment brewed among the exiles in Babylon, seeking as they did to find meaning in the inexplicable series of tragedies they had suffered and at the same time trying to address the future of their relationship with Yahweh. How were they to “sing the L

ORD’S

song in a foreign land” (Ps. 137.4), and what place should their ruined city and Temple have outside the confines of their tenacious memories? Genesis 1–2.4, which envisions the entire created universe as God’s sanctuary, where worship occurs in sacred time (the Sabbath) rather than space, can be read as one exilic response. An important element of the exiles’ theology, however, also involved hope for a return to Judah and Jerusalem and for restoration of the Temple (programmatically outlined in Ezek. 40–48)—not unexpectedly so in view of the close link before the exile between the upper class of Judah and the Temple establishment. The theme of a restored people, city, and active Temple is central to the narrative of Ezra-Nehemiah, the biblical text that provides the most extensive treatment of the Judean restoration in the Persian period. These books are supplemented by parallel material in the prophetic books of Haggai and Zechariah, the apocryphal book 1 Esdras, some data in Chronicles, and Book 11 of Josephus’s

Antiquities.