The Oxford History of the Biblical World (69 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Ezra 2–3 (see also Neh. 7) describes the return to Judah of Zerubbabel and Joshua with a huge company of Babylonian exiles. They immediately establish an altar in Jerusalem, resume sacrifices, and begin the rebuilding. Ezra’s dates for this event are vague, and the historicity of the Ezra narrative is called into question by the virtual silence of both Haggai and Zechariah (but note Zech. 6.10) on the subject of exiles or the expectation of a large-scale return. Perhaps the Temple-building activities did not involve any significant group of recent arrivals, or perhaps returned exiles were only one of several Jewish parties originally involved in the Temple restoration.

From the ideological perspective of the Ezra-Nehemiah narrative, the only legitimate Israelites are the “exiles.” But it is clear from the same narrative and elsewhere in the Bible that as the Persian period progressed other Jewish groups challenged the “exiles.” Some of these Judeans were probably responsible for the so-called Solar Temple at Lachish, which has been dated to the time of Darius I. Similarities between Ezra’s descriptions of exilic “return” and the story of the Exodus (compare Ezra 1.6 with Exod. 12.35–36) suggest that typological and ideological considerations maybe obscuring historical data about the activities and motivations of Zerubbabel and Jeshua. Still, just because a story conforms to a literary pattern is not reason for total skepticism; tablets found in Syria attest that early in Darius’s reign at least one other exiled ethnic group returned from Babylonia to its ancestral home. Whenever it was that they arrived in Judah, returned exiles were an important Judean interest group by the time of Zerubbabel, in close communication with supportive like-minded exiles in the Diaspora. Ultimately the “exiles” or their ideological heirs gained the upper hand in Jewish political and religious affairs, and their version of the events of the restoration dominates the biblical record.

Attempts to understand the Temple restoration movement of 520 focus both on the rebellions of subject nations against Darius in his early years and on the implications for Judah of Darius’s imperial reorganization. Did the upheavals in the Persian empire associated with Darius’s rise to the throne suggest to the Judahites that the time had come for a political and spiritual renewal in Judah, even the restoration in some form of its preexilic identity? The close conjunction of Darius’s accession with the dated activities of Haggai and Zechariah, who use messianic language associated

with preexilic Davidic kings to extol David’s descendant Zerubbabel and the high priest Joshua (Hag. 2.20–23; Zech. 3.8; 6.11–14), has suggested a short-lived movement to overthrow Persian hegemony in Yehud. Like Sheshbazzar (and later, Ezra and Nehemiah), Zerubbabel and Joshua drop inexplicably from the biblical record, even before the Temple is completed in 516/5 (Ezra 6.15–16). Were they punished as rebels? Or recalled to Darius’s court? Recent scholarship is turning away from the rebellion theory; perhaps Zerubbabel died a natural death around 516–515, or he may have succumbed to opponents in an internal Judean power struggle.

Precisely when Zerubbabel became the second attested governor of Yehud is unclear. If Zechariah is prophesying in expectation of Zerubbabe’s arrival in Jerusalem he would have to be a Darius appointee, but in Ezra 5.2 Zerubbabel is already governor when Zechariah begins his ministry, perhaps appointed recently by Darius or even earlier by Cambyses. Viewed in the context of Darius’s reforms, the presence of a governor of the Davidic line could reflect a new imperial attitude toward the region. Zerubbabel would not have been the only local dynast administering a minor satrapal province. Darius made a regular practice of deputizing native experts on provincial affairs, including religious matters, as in the case of the Egyptian Udjahorresnet.

According to Ezra 6.6–12, in his second year (520) Darius gave orders that the work already begun on the Temple could proceed with the added incentive of financial support from district revenues (6.8). Thanks to imperial endorsement, perhaps some limited imperial funding, donations from wealthy exiles (Zech. 6.10–11), and the exhortations of Haggai, Zechariah, and additional unnamed prophets (Ezra 5.2; Zech. 7.3; 8.9), the Temple was completed in 516 or 515 (Ezra 6.15). Ezra 6.16 describes the dedication ceremony celebrated by the priests, Levites, and the rest of the returned exiles followed by observation of the Passover (6.17). The date of 516–515 for this joyous event (in Ezra 6.15 only) cannot be confirmed. By including this date notice, the Ezra narrative can claim that the seventy-year desolation Jeremiah had predicted (Jer. 25.11–12; 29.10) ended almost exactly on prophetic schedule.

Once again, animal sacrifices could be burnt by the priests on the altar each morning and afternoon. But in spite of the Temple’s symbolic, religious, political, and economic centrality, the Bible contains no descriptions of its actual dimensions despite its duration for five centuries, the longest surviving Jerusalem Temple. Herod’s Temple (begun in 20

BCE

) was a wholly new structure, technically the “Third Temple,” and can provide no information about its immediate predecessor. The archaeological evidence for the destruction of Jerusalem is abundant, but the site of the Temple has not been excavated. In constructing their new Temple the rebuilders would have returned to the site of the original structure, thus conforming to traditional practice in which sacredness of place persists through time. They would have followed the plan of the old Temple, whose foundations and dimensions could probably be seen in the ruins. They also had the Pentateuchal tabernacle texts and the Deuteronomic Historian’s descriptions of the First Temple.

There is no way to ascertain the nature of Sheshbazzar’s earlier “foundation” or of the altar raised by Zerubbabel and Joshua as a prelude to their successful rebuilding. The stylization and allusiveness of the narratives concerning the Temple limit their historical and descriptive value. The narration about this period stresses the newness—hence the purity—of the new building, as well as its continuity with the First Temple. It underscores that the vessels of the First Temple were once again being put to use in the traditional sacrificial rituals. Rabbinic tradition, however, lamented that the First Temple possessed five things the Second lacked: “the sacred fire, the ark, the urim and thummim, and the Holy Spirit (prophecy)” (P.

Taanit2.l

[65a]).

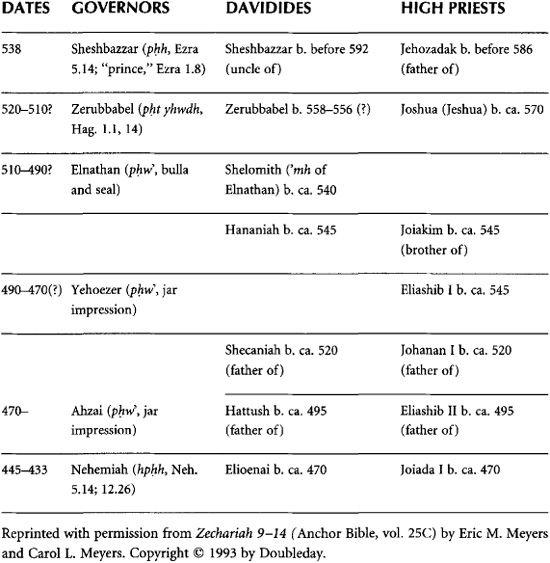

Table 8.1 Governors, Davidides, and High Priests of Yehud in the Persian Period (538–433

BCE

)

The Jewish rebuilders of the Temple clearly subscribed to the ancient Near Eastern—and preexilic Jerusalem—worldview (see Ps. 68.34–35) that a nation’s well-being depended on the maintenance of the central sacrificial cult (Hag. 2.9). This explains why Haggai and Zechariah were so anxious to energize the dispirited population that had allowed the Temple to remain in ruins (Hag. 1.2–6). Both these postexilic prophets use language reminiscent of Ezekiel and Second Isaiah in their message of God’s imminent action in the lives of Judah’s people. The return to the

Temple of God’s glory (Hag. 2.8–9; Zech. 8.3), of God’s manifest presence (Ezek. 43.1–5), would reverse Yahweh’s curse on the land, the prophets’ explanation for the poor harvests, blight, drought, poverty, and stagnant economy (Hag. 1.5,10–11; 2.16–17; Zech. 8.10–12). The presence of God’s glory would usher in a new era of prosperity (Hag. 2.9; Zech. 8.12–15). Zechariah’s extravagant vision of the golden lamp-stand flanked by olive trees (Zech. 4.1–6, 10–14) calls to mind ubiquitous ancient Near Eastern tree-of-life symbolism (see Gen. 2.9; Prov. 3.17–18; 11.30). The visions of Zechariah 1.7–6.15 in particular may be viewed as an essay on early postexilic Temple symbolism. Echoing standard ancient Near Eastern as well as biblical literary and visual imagery, Zechariah refers to the Temple as the sacred mountain (Zech. 4.7; 8.3), which connects earthly and heavenly realms. As such it is the locus of God’s covenantal law and justice (Zech. 3.7; 5.1–4).

Curiously, despite their shared purpose, the contemporary prophets Haggai and Zechariah do not make reference to each other, and their rhetorical styles differ. Unlike other prophetic books, the book of Haggai is written entirely in the third person, as a historical narrative rather than a first-person delivery of Yahweh’s word. Nonetheless, both prophets address the corollary principle of preexilic Temple ideology, namely, the Zion/David theology. Most notably expressed in Psalms, this theology proclaimed that the king rather than the priesthood bore primary responsibility for protecting and promoting the national worship. Haggai more than Zechariah retains the older monarchical ideals, specifically in association with Zerubbabel. Repeating God’s description of exiled King Jehoiachin (Jer. 22.24), Haggai (2.23) dubs Zerubbabel God’s “signet ring,” a mark of honor and of the governor’s function as God’s divine representative. By contrast, the book of Zechariah makes more guarded references to Zerubbabel and kingship (Zech. 3.8; 4.6–10; 6.12–13), preferring to stress a joint messiahship of prince and priest. Zechariah wants to reassure the citizens of Judah that their quasi-national status, newly reembodied in the restored Temple ritual, did not depend on the old preexilic form of monarchy. Both Haggai and Zechariah, however, avoid mentioning an important part of the priestly mandate throughout the empire, namely, prayers and sacrifices for the well-being of the Persian king and his sons. Ezra-Nehemiah pragmatically accepts the necessity for the prayers without question (Ezra 6.10).

For Zechariah, who came from a priestly family (Zech. 1.1,7; Ezra 5.1; 6.14; Neh. 12.4, 16), Davidic kingship lives most compellingly in Israel’s memory and in eschatological expectation. Real power belonged in the hands of the Zadokite priesthood, whose exclusive claim to administer the Temple appears earlier in a programmatic text in Ezekiel 44. This apparent expansion of priestly power is a postexilic phenomenon, and, in fact, convincing evidence for the anointing of a high priest is only found in postexilic literature. By the Hasmonean period (mid-second century

BCE

) the high priest was exercising the function of the king. The fading of kingship from actual Judean experience accompanies the gradual disappearance of prophets in the classical mode and the growing power of the high priest.

From a symbolic standpoint, where the new Temple differed most from the old was in having no royal palace immediately adjacent to it. This difference signaled the adjustments to Judean royal ideology alluded to in Zechariah 1–8. However, a measure of continuity between old and new may be exemplified by the citadel that Nehemiah

apparently built just north of the Temple precinct around 445

BCE

(Neh. 2.8; 7.2). Probably garrisoned by troops of the Persian military establishment, this citadel adjacent to the Temple would have constituted the Persian-period equivalent of the preexilic royal compound. The citadel signified monarchical control of the land’s institutions, though now the monarch was the Persian king. Similarly, the biblical books least resistant to the Persian presence in Jewish lives (Haggai, Zechariah, Ezra, and Nehemiah) date events as a matter of course by the Persian king’s regnal year.

The community of returned exiles was frequently at odds with the indigenous population, among them nonexiled Judeans and Samarians, who also professed allegiance to Yahweh. Biblical references to the comparative wealth of these immigrants from Babylonia (Ezra 2.68–69; 8.26–27; Zech. 6.9–11) reinforce the suspicion that they had to be well-off in order to finance their return in the first place. The Ezra-Nehemiah narrative suggests that even some sixty years after Zerubbabel the families of returnees had maintained their identity as social and economic elites, distinct from the local population, who were poorer farmers and peasants. Did the returned exiles, who were, after all, strangers to their ancestral lands, clash with indigenous Judeans and foreign opportunists (such as Edomites) who had taken over their property in their absence? Did the returnees settle down only in unpopulated land, perhaps just south of Jerusalem? Did they force wholesale evictions? Dominated by an “exilic” perspective, the Bible is virtually silent on these embarrassing questions.

From a sociological perspective, Judah like other agrarian societies was characterized by social inequality. A class-based breakdown of the population and distribution of wealth illuminates both the social tensions and the inner-Temple struggles to which the biblical record alludes. The majority of the population consisted primarily of peasants and artisans, along with petty criminals and underemployed itinerant workers who lived by their wits or off charity. Ethnographers and historians suggest that the governing class—particularly the priestly families in postexilic Judah—averaged about 1 percent of the population but controlled as much as a quarter of the national income. Together, the ruler (the Persians) and the governing class (primarily the Zadokite priestly families) in general could have received not less then half the national income.