The Oxford History of the Biblical World (73 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

With the arrival on the scene of Ezra and Nehemiah in the mid- to late fifth

century, the boundaries between Jew and non-Jew began to be defined more narrowly. The reforms were controversial, but the Persian empire stood on the side of Ezra and Nehemiah, and resistance could have been risky. Even so, in view of the continued relations between Jerusalem and Jews of Samaria, Ammon, and Egypt in the decades after Ezra and Nehemiah, the new restrictions were not immediately enforceable.

The prevailing heterodoxy of Persian-period Judaism with which Ezra, Nehemiah, and their followers struggled is illustrated by two controversial items, a coin of Judah engraved with an image that must have been someone’s idea of Yahweh, and the subversive book of Job. The coin, a unique silver quarter-shekel now in the British Museum, is inscribed

yhd,

Yehud, in Aramaic lapidary script and assigned to the early fourth century. On the reverse a bearded deity carrying a falcon or eagle on his outstretched left hand sits on a winged wheel. If not for the inscription, the iconography would suggest a Greek deity such as Zeus or an eastern Mediterranean god identified with him. The inscription, however, demands a Jewish context for the image, and the winged wheel naturally evokes Ezekiel’s vision of Yahweh’s “glory” (Ezek. 1.4–28). Attempts to relegate the drachma to the hand of some ignorant Persian official in Judah disregard the reality of Persian religious policy toward its subject peoples. If Judah issued the coin, the Jerusalem priesthood would have had veto power over the imagery.

The author of the biblical book of Job deliberately created a character who is not Israelite, does not live in Israel, seldom refers to God as Yahweh, and makes no allusions to Israel’s history or its covenant with God. Job is Everyman, his innocent suffering a challenge to retributive ideas of God’s justice especially favored in exilic and postexilic meditations on the catastrophe of 586

BCE

. In particular, this book engages in an eloquent and disturbingly open-ended dialogue with the Deuteronomic, prophetic, and wisdom traditions that dominate the Bible. Even if the book was composed before the exile, as some propose, its presence in the canon testifies to its continued life into the Persian period and beyond.

In the end, Nehemiah’s exclusivistic vision may have resulted in a Judah that looked inward and viewed the outside world with suspicion, but that same vision helped a tiny, impoverished community preserve itself in the coming centuries of tumultuous change.

Jews in the eastern Diaspora had opportunities for advancement under the Persians, as one sees in such romantic, didactic tales of Jewish life in the Diaspora as Daniel 1–6, Esther, Tobit, and 1 Esdras 3–4. The Murashu tablets contain the names of Jews acting as agents for the Persian government or for Persian nobles. Ezra and Nehemiah came from the Babylonian and Persian Diaspora, respectively, and Nehemiah’s position of trust at the Persian court illustrates how proximity to the centers of Achaemenid power enhanced the religious authority of these Jewish communities of upper-class ancestry at the expense of Jewish leaders in Palestine. While many in the Diaspora did not enjoy great wealth—some Jews in Nippur were slaves—economic conditions in Judah were far worse; the Bible mentions Diaspora Jews sending money to underwrite Temple expenses (Ezra 7.16; 8.25; Zech. 6.10).

The religious life of Babylonian Jews is illuminated by a trend in the nomenclature of the Murashu tablets. A century after the exile (ca. 480) a large number of fathers with Babylonian names began to give their sons names with

Yahweh

as the theophoric element. The suggestion has been made that this phenomenon reflects the gradual dominance of a “Yahweh alone” party in the Diaspora, to which Ezra and Nehemiah belonged. Daniel’s categorical resistance to any form of assimilation contrary to Jewish practice (Dan. 1–6) reflects eastern Diaspora concern for maintaining Jewish identity in a later period.

Egyptians are among the peoples Jews are forbidden to marry according to the marriage legislation of Ezra (Ezra 9.1). The Elephantine papyri give a fascinating picture of life during the fifth century in a Jewish military colony on Egypt’s southern frontier. When this community of mercenaries in the service of Persia first came to Egypt is unclear, perhaps as early as the seventh century. Their local temple, whose construction antedated the Temple of Zerubbabel, was dedicated to Yahweh, but they also worshiped a god Bethel and the Canaanite goddess Anat. Despite their apparently syncretistic worship, these Egyptian Jews were not isolated. They corresponded with Jerusalem and Samaria on religious matters, appealing to both cities for assistance in rebuilding their temple when it was burned in local riots and promising as a condition of aid not to sacrifice animals in it. The monotheism that characterizes rabbinic Judaism evolved slowly. Rather than being Judaism of a sadly degenerated form, the Yahwism of Elephantine may preserve ancient elements of Israelite Yahwism, frozen in time. Elephantine Judaism no less than Samarian Judaism must be viewed within the broad parameters of early Second Temple Judaism.

By the late Second Temple period the synagogue had become a common element in Jewish life, both in the Diaspora and in the Jewish homeland. On the basis of logic and the indirect testimony of Ezekiel 11.16, it has been assumed that such an essential Jewish institution must have arisen among the exiles in Babylon. Unfortunately, neither archaeological nor epigraphic evidence supports this theory. The term

synagogue,

meaning “house of assembly,” is Greek, and it did not become current until the turn of the era. The earliest undisputed reference to a synagogue comes from Egypt in the third century

BCE

, where it is called a “prayer house.” Synagogues do not seem to have been part of Palestinian Judaism until the Roman period.

Rather than assume a single line of development, one should conceive of the gradual convergence of several Jewish institutions: a prayer hall, an assembly hall or community center (see Jer. 39.8), a Torah study hall and school, and perhaps also the preexilic city gate where elders gathered to render judgment. Synagogues were a product of the Hellenistic Diaspora, but they were not Temple substitutes. They were not built on sacred ground; they were a lay, not a priestly, institution; and they were not the sites of animal sacrifice. Furthermore, while the Jerusalem Temple remained central in the religious consciousness of Diaspora Jews, this did not prevent some Jewish communities from erecting their own local temples in fifth-century Elephantine (Egypt), on Mount Gerizim in the fourth century, at Leontopolis (Egypt) in the Hellenistic period, and elsewhere. Thus, synagogues, whenever they originated and in whatever form(s), belong to a wide spectrum of possible venues and contexts for communal worship in Second Temple Judaism.

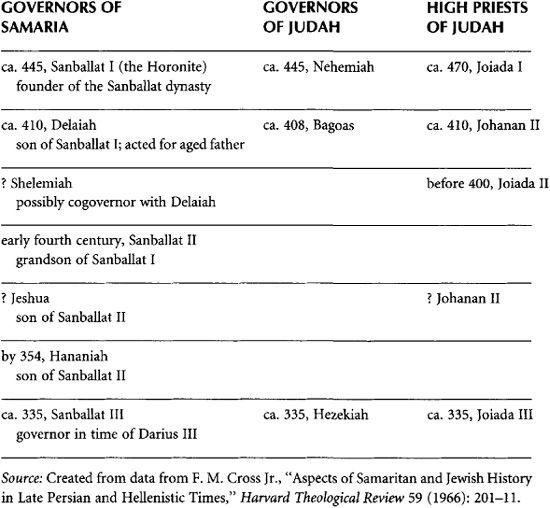

After Ezra and Nehemiah, the historical record again becomes obscure. Both Judah and Samaria maintained their autonomous status within the empire; no evidence for a parallel Persian administrator over the subprovinces beyond the satrap has come to light. The Bible provides the names of high priests (Neh. 12.10–11, 22) and Davidides (living in Judah? 1 Chron. 3.17–24) down to the end of the fifth century. (See table on p. 296.) With additional data gleaned from Josephus, the Elephantine and Wadi ed-Daliyeh (Samaria) papyri, and inscriptions on seals, sealings, and coins, attempts have been made to fill out the list of Judean high priests and the governors of both Judah and Samaria down to 332 (see

table 8.2

). If these reconstructions are accurate, the firm dynastic grip on the Judean high priesthood and governorship of Samaria indicates a level of stability in the two regions. But dynastic tenacity cannot prevent family quarrels or the backing of different political factions (pro- or anti-Persian, for example). Josephus mentions the murder by the high priest Johanan of his brother in the Temple, bringing down on Judah a punishment of seven years of extra tribute

(Antiquities

11.7.1), probably during the reign of Darius II.

Table 8.2 Governors of Samaria; Governors and High Priests of Judah (445–335

BCE

)

Let us end by returning to the larger stage of history. Artaxerxes I died peacefully in 424

BCE

. After a period of violent intrigue, Artaxerxes’ son Ochos emerged the winner and took the throne name Darius II (424–404). The Elephantine papyri concerning the Festival of Unleavened Bread (419) and the ruined temple (410) come from his reign. Aided by the capable diplomats and satraps Tissaphernes and Pharnabazus, Darius II intrigued to foster Greek disunity, even intervening in the Peloponnesian War. Then Darius II was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes II (Memnon; 404–359), a long-lived monarch whose reign was marked by continuous revolts, particularly by Greek city-states. A potentially dangerous attempt to unseat Artaxerxes by his brother Cyrus was thwarted in 401 at Cunaxa (Babylonia), despite the formidable Greek mercenary army assembled by Cyrus and immortalized by Xenophon. By the terms of the King’s Peace (386–376), the Ionian Greek cities for a time acknowledged Persian control.

The loss of Egypt in 405 was more serious. Several times the Persians launched campaigns to regain Egypt, but without success until 343. Although coastal Palestinian cities served as staging points for Persian campaigns, it is unclear whether Samaria and Judah were involved. A move by independent Egypt at the turn of the century up the coast and into the Shephelah as far as Gezer came to an end around 380, when the Persians regained the territory.

Throughout the second half of the 360s the Satraps’ Revolt upset affairs in the Persian empire, but any repercussions for interior regions of Syria-Palestine elude us. Judah is unlikely to have participated in a rebellion of Phoenician cities against the next Persian king, Artaxerxes III (Ochos; 359–338), initiated around 350 by Tennes the king of Sidon. Destruction layers are found at numerous sites, but most of them lie outside Judah, and distinguishing between mid-fourth-century and later Alexandrian destructions has proved impossible. First Tennes (345) and then Egypt (343/2) capitulated to Artaxerxes III.

But disaster soon fell upon Persia. The short, unhappy reign of the Achaemenid puppet king Arses (338–336) was followed by that of Darius III (Codomanus; 336–331), whose even unhappier fate it was to lose his empire to the Greek forces of Alexander of Macedon. After his victory at Issus (333), Alexander marched south into Phoenicia, where all but Tyre submitted to him. A seven-month siege ended in victory for the Greeks, and slavery or crucifixion for the Tyrians. After Tyre, only Gaza dared resist Alexander, who took it before conquering Egypt. There the people hailed him as their liberator from the hated Persians.

No reflexes of Alexander’s arrival appear in the Bible, although Josephus tells a transparently legendary tale of Alexander’s visit to the Temple

(Antiquities

11.8.5) on his way to Egypt. The first explicit reference to Alexander appears in 1 Maccabees. According to Josephus, after submitting to Alexander in 332 the nobles of Samaria revolted and burned Alexander’s prefect to death. Alexander’s army marched north, and the rebels were delivered up to them. The Samaria papyri belonged to these rebels and were deposited with other valuables in the cave where the unfortunate

plotters were found and massacred. Samaria was reorganized and resettled as a Greek colony, while the surviving Samarians rebuilt the city of Shechem as their center. According to Josephus, the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim was built in the late fourth century; he attributes to Alexander the commissioning of the temple

(Antiquities

11.8.4). Recently, excavators at Tell er-Ras, the temple site, claimed to have found the remains of this fourth-century temple.

Much of the biblical material suggests that during the Persian period, both in the Diaspora and in the ancient homeland, Jewish communities were more intent on preserving their past than recording their present. A correct interpretation of their past, they felt, would determine their future fate for good or ill. Chronicles taught lessons based on Israel’s past. The same impulses contributed to the final redaction of the Pentateuch. However, other texts and objects suggest a less retrospective mood. For example, large numbers of locally minted fourth-century

BCE

coins—including coins from Judea and Samaria—have been appearing on the antiquities market. Their small denominations would be useful only for local commerce, not for tribute or international trade. These coins, considered alongside the commercial interests expressed in Ecclesiastes and the buying and selling recorded in the Samaria papyri, suggest a lively local economy.

Archaeological discoveries combined with new analytical approaches to existing information have improved our understanding of the two centuries of Persian rule and have led to reassessments of long-held assumptions and generated new questions. The Persian period’s elusiveness persists, but scholars in search of the roots of Judaism can no longer dismiss it as a negligible interim between exile and Alexander.