The Oxford History of the Biblical World (76 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Antiochus III was far less astute in dealing with a rising western European power that was making its initial forays into the Hellenistic East. The Romans, who until now had been content to flex their muscles on the Italian peninsula and elsewhere in the western Mediterranean, were drawn to the East at about the same time Antiochus had succeeded in capturing Syria-Palestine from the Ptolemies. Although their immediate goal, successfully pursued, was to stop a Macedonian king from enlarging his holdings, the Romans were quick to view aggressive Seleucid activities as equally alarming. A Roman victory over Seleucid forces in Asia Minor resulted in the imposition of harsh, if deserved, penalties, including the requirement that Antiochus and his successors pay Rome a huge sum of money over a decade or so. When the usual sources of revenue proved inadequate for this purpose, Seleucid leaders resorted to the forcible extraction of funds from religious sanctuaries in their territories. In antiquity, temples and similar institutions regularly served as banks, where people felt it safe to leave large sums of money, and they were also the recipients of often lavish gifts from grateful worshipers. We are told that Antiochus III died in an attempt to take wealth by force from such a sanctuary. Throughout his reign the Temple in Jerusalem was spared this ultimate indignity, but its lucrative coffers were to attract the attention of his successors.

During the first part of his reign, Seleucus IV, Antiochus’s son and successor, found it expedient to follow his father’s policies toward the Jews. They had worked in achieving their twin goals of producing peace and revenue. If they also pleased Jewish religious sensibilities, all the better. But just below the surface lay pent-up rivalries and antagonisms among influential families in Jerusalem’s leadership, all of which rose to the surface during the final year or so of Seleucus’s rule and grew in severity during the kingship of his brother and successor, the infamous Antiochus IV Epiphanes. By this time Onias III had succeeded to the office of high priest after the highly regarded tenure of Simon the Just. One of his officials, also named Simon, was stung by the high priest’s refusal to allow him to expand the scope of his responsibilities, and he appealed to the Seleucid governor of the region. While such an appeal was not yet normal procedure for their Jewish subjects, Seleucid officials did regularly intervene in the internal affairs of subject peoples and in extraordinary circumstances. Since the very appointment of the high priest of Jerusalem was subject to their approval, the Seleucids would not have hesitated to intervene here if they thought it sufficiently important and to their benefit. With this in mind, Simon sweetened the deal by pointing out that substantial funds were kept at the Temple, funds that would be very useful for the perpetually cash-strapped Seleucid monarch. When Seleucus’s prime minister, Heliodorus by name, attempted to force his way into the Temple treasury, he was thwarted by the miraculous appearance of two angels—at least that is the story told in Jewish sources. Whatever happened, this much is clear: Heliodorus returned empty-handed to the Seleucid capital of Antioch, but at the same time the Seleucids benefited from learning of splits among Jewish leaders that they could exploit and of treasures they could confiscate when a more propitious occasion arose.

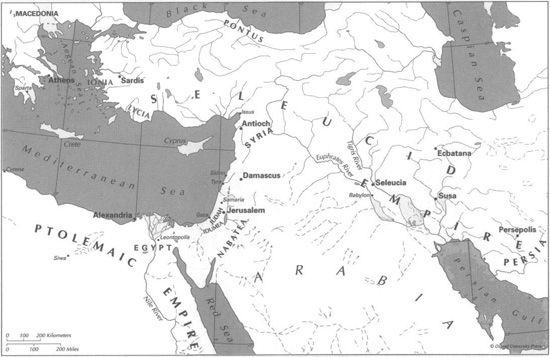

The Seleucid and Ptolemaic Empires

The Seleucids did not have to wait long for such an occasion. When Onias III realized that Simon still enjoyed the support of much of the Jerusalem populace, he judged that his only recourse was a direct, in-person appeal to the king. At about the same time Onias set out for Antioch, Heliodorus murdered Seleucus IV, setting the stage for the succession of one of the king’s younger brothers, Antiochus IV. Onias’s brother, who had taken the Greek name

Jason,

reacted more quickly and successfully to these changed circumstances and through bribery obtained the high priesthood for himself; the subsequent whereabouts of Simon are unknown. Jason followed up his initial success by further bribing the king to allow him to establish a Greek-style gymnasium in Jerusalem and to draw up a list of the “Antiochenes” in that city. Although the exact nature of this latter request is uncertain, there can be no doubt that Jason’s requests and their approval by Antiochus marked a turning point both in Seleucid-Jewish relations and in the internal workings of the Jerusalem leadership. Since Antiochus IV had only recently returned from Rome, where he had long been a hostage for his father’s and brother’s good behavior, he may not have fully understood the likely results of his actions.

Jason had bribed his way into becoming high priest, an action—which unfortunately became a precedent—that could have been viewed as debasing the sacred office. From the Seleucid perspective the Jerusalem high priest was probably no different from any other local leader whose power and very existence depended on royal goodwill. Even if Antiochus were aware of any of these distinctions, it would not have dissuaded him from an appointment that was otherwise so lucrative. Jerusalem “Antiochenes” probably constituted a group of leading citizens dedicated to the promotion of Hellenism, including the cultural activities associated with a gymnasium. Such a development Antiochus could enthusiastically support, despite the probability of opposition from Jerusalem traditionalists.

Surprisingly, Jason’s efforts did not meet with an immediate rejection from the Jerusalem populace. The first few years of his high priestship were relatively tranquil, so much so that Antiochus IV received a favorable welcome when he visited Jerusalem several years later as part of a triumphal tour of his empire. Nonetheless, this appearance of tranquility was soon shattered when the high priest was done in by individuals who had learned from Jason himself how to bribe their way to the top.

Three or four years after his succession Jason sent Menelaus, a brother of his brother’s former opponent Simon, to Antioch on official business. Seizing the opportunity, as Jason had done earlier, Menelaus offered a larger bribe to Antiochus, who appointed him as the new high priest. This led to Jason’s hasty retreat across the Jordan River, where he may have sought the support of the Tobiads (who, however, eventually came down on the side of Menelaus).

Antiochus IV’s decision to intervene in high-priestly politics, which may be viewed as a logical extension of his earlier activities, was bound both to worsen Seleucid-Jewish relations and to exacerbate difficulties among Jews. First, Menelaus was not a member of the family that had traditionally provided the Jews with their high priest. The Oniads traced their lineage back to Zadok, whom Solomon had secured in this position, and Jews worldwide generally agreed that Zadok’s descendants had been chosen by God for the priestly leadership. As noted above, during both Persian and Hellenistic times the office of high priest had expanded to the point that he was leader in secular and economic matters, as well as in religious affairs. Was the issue of Zadokite pedigree, which from the Jewish perspective was crucial, brought to Antiochus’s attention? And would he have cared if it had been? We simply do not know, but apparently here again financial concerns dominated his thinking.

It was in the realm of finances that Menelaus managed to run afoul of both his Seleucid overlords and his Jewish subjects. Having promised Antiochus IV more than he could deliver even through increased taxation and further diversion of Temple revenues, Menelaus resorted to bribery, with golden vessels providing the resources and a Seleucid tax collector as the chief beneficiary. Onias III, still alive and in Antioch, sought to expose these activities, but was killed by Menelaus and his Syrian allies. When Antiochus IV learned that his tax collector was seeking to enrich himself at royal expense, he had his official executed, but no action was taken against Menelaus. Menelaus even managed to regain the king’s favor when a delegation from Jerusalem, enraged by the actions of Menelaus and his supporters, took their complaints against him directly to Antiochus. Again, his success was due in part to bribery.

Jerusalem could not have been a happy place when it was learned that members of its delegation were condemned to death, while Menelaus got off scot-free. Presumably most Jews, apart from those closely allied to the current high priest and dependent on his largesse, were growing increasingly dissatisfied with Seleucid rule, which had begun so auspiciously only thirty years earlier. Perhaps there was also widespread dissatisfaction with the rate and direction of hellenizing among the Jerusalem Antiochenes and others.

Antiochus too may have been angered that the high priest he had appointed could not maintain both a steady flow of income and a tranquil populace. As he planned his next major campaign, against Egypt, he was probably more concerned about the former, but he could not ignore the latter. Trouble in Judea would divert needed attention and resources.

Antiochus achieved notable victories in his first campaign against a weakened Ptolemaic empire. Returning triumphantly north from these initial successes, he stopped in Jerusalem during the fall of 169

BCE

and used this as an opportunity to expropriate huge sums in gold and silver from the Temple treasury. From the perspective of almost all the Jewish community, this was an illegal and impious action.

From Antiochus’s point of view, he was only helping himself to what was lawfully his, with the active support of the Jewish high priest Menelaus. Antiochus had high hopes for a repeat performance when he embarked on his second Egyptian campaign the following year. At first, everything went his way, as he and his victorious troops marched up the banks of the Nile toward Alexandria. But at that very moment, as if on cue, a Roman envoy arrived on the scene and demanded that Antiochus immediately halt his advance and return home. A humiliated Antiochus, unwilling to oppose a force that had humbled his father some years earlier, could only acquiesce.

During this second Egyptian campaign word spread through Judea that Antiochus had died. Emboldened, the exiled Jason returned at the head of a small army to retake Jerusalem. When he and his followers embarked on the systematic slaughter of their enemies, the populace, which otherwise would probably have taken Jason’s side, turned against him and moved to restore Menelaus. Antiochus IV, on his way home from Egypt and in no mood to put up with a rebellion, also actively intervened. The result was further bloodshed and the permanent installation of royal officials who would be able to look out for Antiochus’s and Menelaus’s best interests at close range.

This brings us to 167

BCE

. In hindsight we might think that the course of events from late in the reign of Seleucus IV to this point in Antiochus’s had been leading inescapably to confrontation. For those on all sides who were living through these events, it probably appeared much more mundane. Antiochus needed money, loyalty, and occasionally troops from his subject peoples. At any given moment, there were bound to be problems as well as bright spots throughout his empire. For those in Jerusalem who supported Antiochus, there was a sense that the major source of difficulty lay with their fellow Jews, who stubbornly held on to outmoded ideas and customs and refused to embrace the opportunities that greater participation in the Hellenistic world would afford. No one was talking about the complete abandonment of Judaism, only its modification and updating. Among those who opposed Antiochus, there were many who saw great value in Hellenism, but wished to pursue it in other directions, at different speeds, or under the governance of their earlier overlords, the Ptolemies, who probably looked better as conditions under the Seleucids grew worse. At this point, there were probably few who felt that the very existence of Judaism was at stake.

All of this changed during the second half of 167. The events of those months are easy enough to narrate; explaining them is more difficult. It began when Antiochus sent his general Apollonius to Jerusalem at the head of an army of mercenaries, ostensibly to end feuding among the city’s factions. But he soon initiated a series of more permanent changes. First, he tore down the defensive walls of Jerusalem, allowing for the creation of a single fortified portion within the city called the Akra (“citadel” in Greek). There were gathered Syrian and mercenary forces, foreign residents, and those Jews who allied themselves with Antiochus, including the high priest Menelaus, who along with his associates provided the Seleucids with the detailed knowledge they needed to proceed. Antiochus then imposed a harsh new system of taxation on the Jews.

Such onerous actions were but a prelude to the unprecedented ones that followed. Another Seleucid official arrived in Jerusalem with a decree that struck at the very heart of Judaism. All distinctive Jewish customs and ceremonies were forbidden,

including Sabbath and festival observance and circumcision. All Torah scrolls were to be seized and burned. All sacrifices and offerings to God at the Jerusalem Temple were abolished. Anyone who persisted in carrying out these or other Jewish rites was subject to the death penalty. To demonstrate that the provisions of these decrees were not empty threats, those in charge of Seleucid forces, together with their allies among the Jews, began a concerted and public effort to implement them. Nowhere were their actions more provocative than at the Temple itself, which they turned into a place of worship for the Greek god Zeus Olympius. The altar on which daily sacrifices had been offered to the God of Israel was desecrated, and in its place an altar to Zeus was erected. On 25 Kislev 167

BCE

(during the first part of the winter) a pig was sacrificed on this altar, a direct insult to the traditions of Judaism. Statues of Greek gods appeared in the Temple and elsewhere in Jerusalem. Throughout Judea, into Samaria, and to a lesser degree elsewhere in his empire Antiochus IV seemed determined that the monotheistic faith of Israel be utterly destroyed and that those brave or foolish enough to resist be killed.