The Pirate Queen (10 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

Â

Such were our deeds / In former days,

Â

That we heroes brave / Were thought to be.

Â

With spears sharp / Heroes we pierced,

Â

So the gore did run / And our swords grew red.

Â

Now we are come / To the house of the king,

Â

No one us pities. / Bond-women are we.

Â

Dirt eats our feet / Our limbs are cold,

Â

The peace-giver we turn. / Hard it is at Frode's.

The story of the millstone appears also in Saxo Grammaticus's

History of the Danes

which drew on Icelandic literature. Here it is the Nine Daughters of Ãgir, the ocean god, who grind out the meal of Prince Hamlet. “They set the ocean in motion as if a quern were turned round and they crushed out life between the stones. Far out, beyond the skirts of earth, the Nine Maidens of the Island-Mill stir amain the most cruel Skerry quern.”

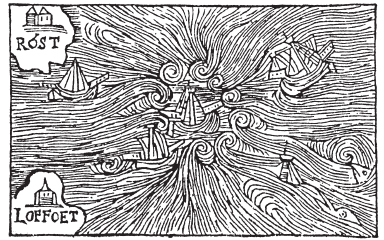

Ships caught in the maelstrom off the Norwegian coast

As far back as the

Odyssey

there have been stories of giantesses who turn a millstone under duress. Whirlpools were once called the navels of the sea, and the drowning of the millstone has been given a dozen mythic meanings. A less mythic but equally poetic description of a whirlpool comes from the

Sailing Directions for the Northwest and North Coasts of Norway,

as quoted by Rachel Carson in

The Sea Around Us:

As the strength of the tide increases the sea becomes heavier and the current more irregular, forming extensive eddies . . . These whirlpools are cavities in the form of an inverted bell, wide and rounded at the mouth and narrower toward the bottom . . . Fishermen affirm that if they are aware of their approach to a whirlpool and have time to throw an oar or any other bulky body into it they will get over it safely; the reason is that when the continuity is broken and the whirling motion of the sea interrupted by

something thrown into it the water must rush suddenly in on all sides and fill up the cavity.

O

N THE

quay I had plenty of time to mull the mythology and geometry of whirlpools as I watched the ferry make a pass at the dock and then retreat. It seemed as if there was no way it could find its way through the tall waves beating against the quay. If it sank offshore, what a terrible sight that would be. Equally terrible was the prospect of the boat's disembarking its passengers and collecting us for the return crossing.

“You're American, right?” a voice emanating from a dark poncho said over my head. A new prospective passenger had joined us. He hadn't been on the bus but had been hitchhiking. His name was Matt and he was a rangy twenty-five-year-old from the San Francisco Bay Area.

“This is something, isn't it?” he said admiringly. “You think we'll make it? Where you going, anyway? I'm going to the Orkney Islands and maybe I'll get to the Shetland Islands. You're going there? Cool! You're going to the Faroe Islands? Where are the Faroe Islands? Wow! I want to go! Can I come?”

His fresh-faced excitement was a distraction in any case. The four or five ladies around me were a tight-lipped bunch. I had earlier felt myself to be the only tourist except for a quiet Englishwoman who was going to Stromness to take a painting course. Now there was me and Matt, two Americans, and he was so American that he infected me, and my gender became less important than my nationality. All the ladies moved slightly away from us and I could hear them thinking, So boisterous, these Yanks.

But I noticed that Matt's appearance on the quay made me

feel more cheerful, and certainly more intrepid. “It is something, these waves. It's great,” I said firmly. Underneath our streaming rain gear, Matt and I had the same hearts, beating with the desire for adventure on the high seas. He asked me more about my trip. “Wow, you're going to Iceland, and to Norway! You're going by boat all the way? That is so cool.”

The ladies looked flabbergasted by the notion of all this sea travel. It was plenty for them to think of getting on this boat. “Oooch, aaach,” they'd been saying to each other. “And me with my stomach.”

The ferry finally docked intact, and the passengers disembarked looking only slightly green. “Come on, ye,” waved the crewmen to us. Their skin was soaked, and water gushed off their yellow slickers. “Get on, get on.”

Matt dared me to go on the upper deck. Even tied to the quay the boat was rolling like a top. It was hard to even get up the stairs. When the ferry pulled away from the dock we were enveloped in a vicious mist. The wind carried off the rain droplets before they hit our faces, so it almost felt as if it weren't raining, but rather that water was attacking us from all sides like a manic, cold car wash. The roar of the boat and the wind was inconceivably loud. Around 325 B.C. the Greek explorer Pytheas wrote that the North was the sea-lung of the world. He wondered if the northern seas were the end of the earth, a place where sky and land no longer separated but surged together in endless chaos. I expect he wrote that description attempting to cross the Pentland Firth.

We went downstairs and peered out the fogged-up windows. I told Matt the story of Finnie and Minnie and the magic quernstone. I'd hoped to see the island of Stroma and the Swelchie, but they were lost in the mist. Storm cauldrons and

millstones with holes through which all the waters of the world gush are all very well to read about, I suppose, but perhaps it was for the best that our route took us well away from them. I settled back to listen to Matt's travel soliloquy:

“So you can only go to the Faroe Islands once a week by boat well that wouldn't fit into my plans because I don't have that much money and it's probably expensive and then I have to work out how to get back to the Mediterranean I'm on a six-month trip and I'm actually hoping to get to India so if it took two weeks to get to the Faroes because you'd have to hit the days right and I didn't plan to spend so much time up here but I am sure interested in all these places . . .”

And I thought of Finnie and Minnie off in the mist, singing their songs of lost power and getting ready to chuck the millstone in the sea (“You want salt? We'll give you salt, Buddy.”) and to move on with their own lives.

“What's your name, by the way?” Matt asked. He was really a nice guy, though a little bit too gee-whizzy.

Minnie? Finnie? Muileartach?

“Bonnie,” I said, sticking out my hand. “Bonnie Stuart.”

“Cool,” said Matt.

T

HE SCOTS

, Orcadians, and Shetlanders have an extensive folklore about the sea, but there are more stories about sea witches than about sea goddesses. It's in cautionary tales for children that we find lingering traces of the whirlpool queens once so revered. These folktale witches are more malicious than terrifying; when they take to the sea, they use eggshells as boats. No ordinary eggshells will do, of course; they must have been emptied by good people, decent people, or else they wouldn't float. This was why children were taught to crush their eggshells carefully after they'd eaten the contents. Inattentive children and wicked children forgot this or purposefully disobeyedâthat's the reason there were always plenty of eggshells about. A witch who wanted to set out to sea would secure her eggshell boat to a “lucky line” that attached to a rock on shore. If, by chance, the line broke, the witch had no means of returning to land.

“Lucky lines,” clews, threadsâespecially red threadsâthese spider-spun strings turn up frequently in stories of sea witches. The Orcadian folklorist W.R. Mackintosh tells us that sorcerers have used colored clews since ancient times, and that the notion of the sacred thread comes originally from the Hindus. Threads are dangerous and powerful.

In windy transactions, a mariner would buy a thread or bit of

rope from a witch. On the thread, the witch tied three knots, with a chant for each knot. The witch then told the mariner that if he wished for a light wind, he should undo the first knot. For a stronger breeze, he should undo the second. But on no account should he unloosen the third. Of course, that's exactly what many curious or impatient sailors did doâwith the result that they created hurricanes, were blown off course, and all around the sea.

Besides threads, a sea witch might bang a wet rag wrapped around a piece of wood against a stone, saying twice over:

Â

I knock this rag upon this stane

Â

To raise the wind in the devil's name.

Â

It shall not lie till I please again.

A witch might also fill a vessel with water and place a cup on its surface. Then she would stir the water with her finger until the cup sank. Alternately the witch might float a small wooden bowl on the surface of milk in a churn. She would then pronounce spells that so agitated the liquid that the bowl was flooded and sank. Many a ship went down, it's said, because a witch bore some malice against its captain. The Scottish witch Margaret Barclay was said to have sunk a ship by making a wax model of it and tossing it in the waves.

Going to sea was an activity fraught with superstition in most cultures, but the fishermen of the northeastern coast of Scotland and the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland seemed particularly prone to worry. It was unlucky to meet a red-haired person, or anyone who was flat-footed, or a dog, or a minister on the way to the boat. In some fishing villages asking a man where he was off to that morning was enough to make him turn around and head back home.

It was important to turn your boat in the direction of the sun; bad luck came to those who turned it widdershins. Once on board there were many words that could not be uttered:

minister, rabbit, salmon, pig, salt.

Many sailors believed that wind could be produced by whistling. No housewife would think to blow on her oatcakes after she took them from the oven. To do so meant a hurricane would surely arise at sea.

In the rough seas of the North, vessels contending with fog, wind, storms, and gales were constantly lost, and seafarers through the centuries prayed for safe sea passage to Celtic, Roman, and Christian goddesses at shrines on the coasts of the North Sea, the Baltic, and the Atlantic. At one time or another Isis, St. Gertrude, and the Virgin Mary were all invoked. One of the most enduring of the marine goddesses was the Celtic Nehalennia, whose sanctuaries have been found around the North Sea, and whose cult drew devotees with business interests across the waters, wine merchants and traders in fish and pottery, as well as sea captains. On some stone shrines she appears to be standing on a ship's prow, handling an oar or a rope; sometimes dolphins accompany her. Her name may mean “steers-woman.”